CONTENT WARNING: This article deals with the topics of abortion, miscarriage and pregnancy loss and may be distressing for some readers. If you or someone you know needs help, you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

In lot 108 of Rome’s largest graveyard, Flaminio Cemetery, there is a corner filled with crosses. Some crosses have been painted white, some are metal, and some have fallen to the ground, but all of them bear the names of women.

The names they carry, however, are not of the deceased buried beneath them, but of women who chose to have abortions. The graves hold the fetal tissue from those abortions, with some dating back as far as 2004.

According to The Guardian, the graves situated in Flaminio Cemetery’s so-called “fields of angels”—corners of Italian cemeteries devoted to the burial of aborted fetuses—were discovered in early October 2020, after one woman, whose curiosity was piqued upon reading about the practice in local newspapers, discovered a plot with a wooden cross bearing her name and the date on which the fetus was buried in another Roman cemetery.

She then shared her discovery in what became a viral Facebook post with more than 10,000 shares, reigniting Italy’s ongoing abortion debate and sparking something akin to a second wave of the Italian #MeToo movement.

Another woman named Francesca*, a 36-year-old teacher living in the Italian capital, recalled almost fainting upon seeing her own name and the date December 23, 2019, among the tombs. Per The Guardian, she chose to terminate the pregnancy at six months, after being told the fetus was malformed, and unlikely to survive the full term. The outlet reported that it took 10 days before a hospital agreed to perform the procedure in September 2019.

“The pain I felt in that moment reawakened a year-long trauma. And I suddenly cried all the tears I had in my body,” she told The Lily News.

Speaking to Agence France-Presse, Francesca said she felt “betrayed by the institution”.

“To think that someone appropriated her body, that a rite was performed, that she was buried with a cross and my name on it, was like reopening a wound,” she said.

In her conversation with The Guardian, Francesca said she had never agreed for the fetus to be buried there, nor had she consented to having her name used in any way.

“I repeatedly asked the hospital what happened to the fetus, and they made me believe it had been thrown away,” she said. “So where was it for three months? Then for it to be buried with the symbol of a cross, which I don’t adhere to, and with my name on it—it felt like a punishment.”

The hospital where the woman who first exposed the burials had the abortion denied responsibility for sharing her name, issuing a statement saying that the remains of fetuses were identified with their mother’s names strictly for transport and burial permits. The information was then passed on to Ama, the public services firm that manages Rome cemeteries, which also denied responsibility, saying it does the burials after orders from the health authority.

Since the “fields of angels” came to light, 130 women have spoken out, contacting Differenza Donna (Difference Woman), a Rome-based women’s rights organisation, which has been gathering testimonies to co-ordinate joint legal action, citing violation of sensitive personal data.

“We were aware of the existence of fetus cemeteries, but nothing like what we witnessed at Flaminio, where full names are publicly exposed and women’s privacy violated,” Elisa Ercoli, president of Differenza Donna, told The Lily News.

“It was an attack on all of us, an episode of institutional violence that made us realise how many obstacles we still try to overcome on a daily basis despite the legalisation of abortion in Italy in 1978.”

Shocking though it may be, the burials aren’t technically illegal. They are allowed under a 1990 law, adapted from one dating back to 1939, which was established under dictator Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime.

Under the present law, which is applicable to abortions and miscarriages, parents have 24 hours to claim the remains if the fetuses are less than 20 weeks old. In the case where no request is submitted, their rights to ownership are forfeited, and local health authorities are permitted to make decisions around burials. Since the passing of the 1990 law, it has become common for third parties to have agreements with hospitals to handle the disposal of the fetuses.

Per POLITICO, the most prominent group doing this is Difendere la vita con Maria, which has 3,000 members and says it has carried out over 200,000 burials. The group takes donations for funding to carry out burials on its website, which says: “For only €20 you can bear the cost of burying an unborn child.”

A spokesman for the group, Stefano di Battista, told POLITICO that they do not presently work in Rome, but in the cities where the group does work, they collect fetuses, usually once a month, from the hospitals with which it has contracts, before burying them following a brief ceremony. He also told the publication that they never reveal the identities of the women, saying:

“Anonymity is a guiding principle for us. We do not do this practice to battle against abortion rights. We are not interested in crusades. We believe it is at the basis of civilisation to bury with dignity and piety the children that never came into the world.”

Monica Cirinnà, a senator in the Italian parliament, spoke to POLITICO as well, stating that the burials are “attacks on women’s freedoms”.

“Every woman who terminates a pregnancy has the right to choose if and how to bury the fetus and according to which ritual. These are deeply personal decisions that cannot be brought into question,” she said.

“Even today, women’s bodies are battlefields. Attacks on women’s freedom, regarding the choice to become or not to become mothers, are now coming from everywhere, continuously undermined by small, silent but insidious procedures like this one.”

Similarly, Silvana Agatone, president and founder of LAIGA, the Italian association for doctors who carry out abortions—and one of the few gynaecologists who carried out abortions in Rome prior to her retirement—also told POLITICO that the burials were “the most serious violation of privacy”.

“Many women do not tell relatives or friends about the procedure. It is a way of punishing the women by creating a sense of guilt,” she added.

“To have a tomb with your name on it implies that you are as good as dead.”

Despite the archaic law’s existence, women do have a legal right to privacy when it comes to abortion, one which is protected by the 1978 law that made abortion within the first 90 days of pregnancy legal in Italy. This law, however, also allows for ‘conscientious objectors’ among medical professionals, meaning that doctors can refuse to perform abortions because of their personal beliefs.

As of 2017, seven out of 10 gynaecologists in Italy fall into this category—with the number even higher when narrowing in on some parts of the country. This number went up 10 per cent in the past 20 years, according to a government report released in December 2018.

In Rome, women can access what are known as ‘therapeutic abortions’, which are carried out when the mother or baby’s health is deemed to be at risk, and can only be performed at five hospitals due to the lack of medical staff agreeing with the procedure.

However, the acceptance of ‘conscientious objection’ has also seen doctors refuse to perform abortion even when the baby or mother’s life is at risk. In 2019, seven Italian doctors who refused to perform a potentially life-saving abortion were put on trial for manslaughter.

The trial, which commenced in Catania, Sicily, in September 2019, focused on the 2016 death of 32-year-old Valentina Milluzzo, who was five months pregnant with twins. Members of Milluzzo’s family gave evidence in the trial, saying that when Valentina had been admitted to hospital with complications, doctors told her that her unborn twins would not survive. They refused to abort the pregnancy on moral grounds, which ultimately led to fatal sepsis, causing one twin to be lost in the womb, before killing Valentina.

During the trial, her father said:

“We are victims of ignorance and negligence. I still remember the heartfelt invocation: ‘Mom, I’m dying’. And I remember the words of the doctor on duty: ‘As long as I hear the hearts beating, I cannot intervene because I am an objector’…”

According to the Italian health ministry, in the south of Italy, an average of up to 80 per cent of doctors who are qualified to carry out abortions refuse to do so on moral grounds. Per Financial Times, in the southern region of Molise, just one doctor carries out the entire region’s abortions, and in Sicily, only one in 10 gynaecologists performs the procedure.

Even prior to its legalisation, abortion has been staunchly opposed by an alliance of religious and political conservatives, with pro-choice campaigners saying that the Catholic Church’s stronghold on various Italian institutions has made the implementation of reproductive rights particularly difficult at every turn.

“The central problem is that the Church considers this country its own,” Elisabetta Canitano, a gynaecologist and founder of women’s health non-profit organisation Vita di Donna, told Financial Times in October 2019.

The outlet also reported on the intimidation some women receive by medical staff after terminating pregnancies. Valentina Magnanti, a Roman woman, sued the hospital where she had her abortion after she was called “an assassin” by hospital workers who waved Bibles at her. Per Financial Times, after her doctor’s shift ended, the staff refused to help her, leaving her to deal with the abortion in the toilets.

According to Agatone, the issue is also deeply entrenched in the medical system, with junior doctors often fearing that their career will suffer if they don’t choose to side with the objectors, and heads of department refusing to hire non-objectors.

Rossana Cirillo, a doctor in Genoa, told Financial Times that she eventually decided to be an objector because she was overwhelmed by the workload of “800 abortions a year”.

“I do not identify as an objector,” she said. “I was working so much it became unsafe for the women.”

With access to abortion so limited across the country, delays are common, increasing women’s chances of passing the lawful 90-day window in which they are permitted to have the procedure. As a result, waiting lists are long and women travel abroad when they can afford it, with illegal abortions punishable by fines.

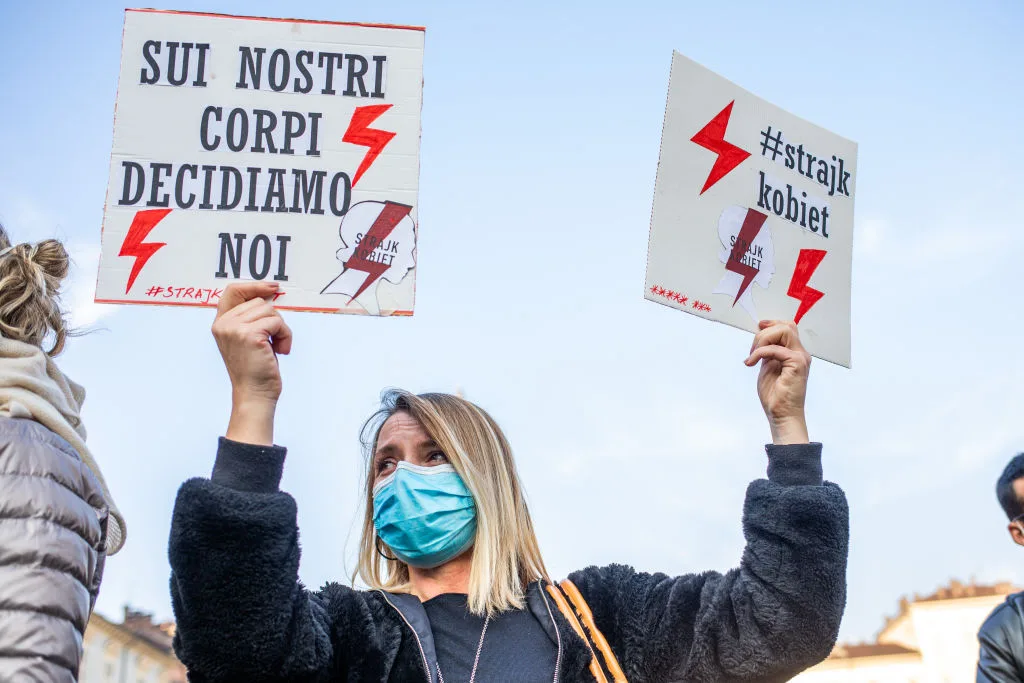

In Italy, and many other places around the world, the fight for full reproductive rights, unhindered by religion, is nothing new. However, the discovery of these “fields of angels” has only served to further fuel the women of Italy in the most recent resurgence of their fight, one which coincides with the nation-wide protests occurring in Poland against banning abortion entirely.

On October 31, 2020, women took to the streets of Turin in the Piedmont Region of Italy, to protest against local legislation that further limits access to the abortion pill, RU486, and the proposed Polish anti-abortion laws alike. Under the new Piedmont law—a precedent that women fear will spread to other regions in the country—not only would access to RU486 be further limited, but it would offer support to pro-life advocates by allowing them to enter health facilities where women are having abortions.

“The circular announced by the Region severely limits access to RU486, reserving it only for hospitals and not for consultants,” said Antonella Veltri, president of Di.Re., the national network of anti-violence centres.

She continued: “Self-determination over one’s own body is the heart of women’s freedom of choice and of the equality of rights enshrined in the Constitution in the recognition of gender difference. The entry of the Pro Vita organisations into the health structures where women start the process of terminating their pregnancy reaffirms the patriarchal power of control over the body of women which is at the root of violence against women.”

The situation for women in Italy is an ongoing one, as is the one in Poland, where pro-choice protests against a total abortion ban also took place in October 2016, almost exactly four years ago.

If the recent movements have proven anything, it’s that women are still second-class citizens in many parts of the so-called ‘first world’. Up until Joe Biden won the U.S. election to become the 46th President of the United States, the appointment of President Donald Trump’s Supreme Court Judge nominee, staunch pro-lifer Amy Coney Barrett, gave weight to fears that historic pro-choice legislature Roe vs. Wade could be overturned, thanks to a now-majority conservative Supreme Court.

Even in Australia, abortion in New South Wales was only decriminalised in 2019, after 119 years, with access around the country, although legal, still shrouded in various limitations.

It is, once again, a sobering reminder that the burden to be the gatekeepers of ‘morality’ virtually always falls on women, no matter where they are in the world, and it is the woman’s name that carries the weight of the ‘crime’.

“In Italy, you give birth to a child, and they will have the father’s name; you have an abortion, and they will have the name of the mother,” Francesca said.

Above all, it is a sign that no matter how progressive a country may seem, we cannot take our rights for granted, and we must continue, as always, to fight tooth and nail for them.

*Name has been changed to protect her identity.