In 2010, actor Andy Whitfield was starring in the hit TV show Spartacus. Then a routine test confirmed his worst fears: aggressive and advanced non-Hodgkin lymphoma cancer. In a new book, Spartacus and Me, his wife, Vashti Whitfield, tells what happened next.

Congratulations, Andy, the scan is clear,” said Dr Doocey. There is no sign of the cancer. I could see tears welling up in Andy’s eyes, which he kept wiping away with his big hands. The relief and joy were intoxicating. We’d kicked cancer. After six months of battling advanced non-Hodgkin lymphoma, we’d beaten it. The cream was Andy still had his TV role. He was the star of a Hollywood television series and hero to millions. Spartacus was back. Andy had renewed energy and excitement about getting back to work. He was back at the gym and excited about filming [in New Zealand].

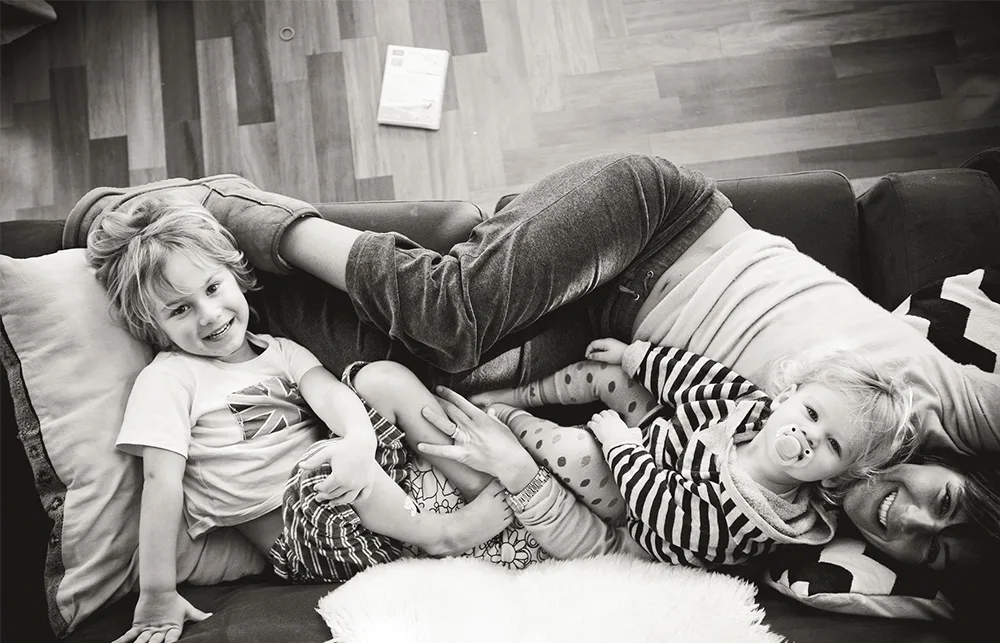

He was feeling well enough to help out at our five-year-old son Jesse’s school, which he loved doing. And he did a lot with our daughter, Indi, who was nearly three years old. He’d pick her up from daycare and take her to the park for a push on the swing, or he’d lie on the floor and play with her. Indi had just started to speak and they had lots of cuddle time. We savoured all of these moments – the precious day-to-day things like going out for a meal together or sneaking off on Andy’s motorbike – which under his contract he was not allowed to ride! This was what life was all about.

Usually, if you’re in remission, you don’t go back for a check-up for three months, but Andy had to undergo medical tests before that. He had to be 100 per cent right for the insurance company to give the green light for the next production of Spartacus. So Andy had to have more blood tests and a scan.

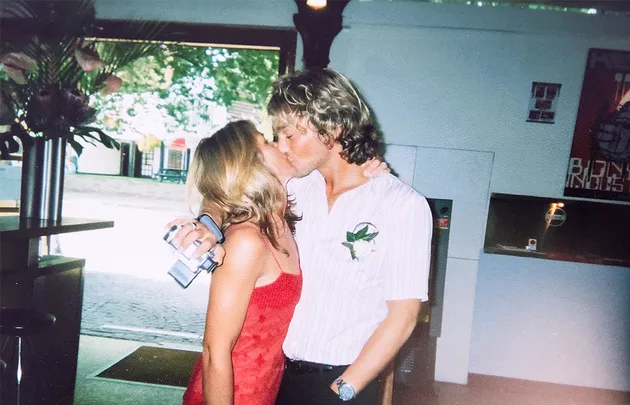

We thought everything would be fine, but so much was riding on the results. The tests showed that a lymph node in Andy’s abdomen was inflamed. The doctor took a biopsy early in the week and we had to wait until the Friday for the results. Over dinner at our favourite restaurant on Thursday, a new tone came into Andy’s voice. “But what if we haven’t beaten cancer, what if I’m not OK?” My mind had wandered to that dark place, too. “Andy, if it’s back, it’s back. We’ll deal with it.” Then I added, “I’ve been thinking about getting a new tattoo – with the words, ‘Be here now’ because that’s all we’ve got. All we have is what we’ve got today.” Andy looked at me with those lovely eyes. “I love you Vashti, that’s why we’re here together.”

As it turned out, there was a tattoo studio nearby. So we wandered across the road and ordered matching tattoos – Andy’s on his forearm, mine on my bicep. It’s not what everyone does for dessert when they go out for dinner, but for us it was about marking a precious moment in time; it was a declaration that we were in control of our bodies and that everything was going to be OK.

The next day we’d get the test results. The doctor was due to ring around 11am, so we huddled on the sofa with the phone between us. The news was devastating. Our doctor said, “I’m sorry, Andy, we have found cancer in a lymph node in your abdomen. We are treating this as if you were never in remission.” The cancer was back. We were being told that Andy could die. It felt like someone had thrown me into icy water and at the point of drowning had lifted me out. That feeling of gasping for air washed over me.

The first step for Andy was to undergo a round of chemo. We told the kids that Daddy had to have more medicine to fix his blood and his hair would fall out. Then Andy said, “Why don’t we cut it off? Let’s have fun.” The kids helped shave Andy’s head. Then they took his hair and made pretend moustaches. We laughed a lot that day. After the chemo, Andy was stiff and sore and was walking like an old man. As we went to the staircase at home he pretended he had a walking stick and put on a hilarious old man’s voice and said, “I am Spartacus”, as if he was 100 years old.

The children were ecstatic – Daddy was home and they all snuggled up on our bed. For Andy, there was a massive bright, shining light at the end of this dark tunnel. If he got through this stage, there was a life-saving bone marrow transplant. Christmas was coming and Santa was going to bring us the best gift ever: time together. Because we didn’t have any hospital visits and Andy was feeling normal, we were able to do simple but beautiful things.

“The most challenging hurdle was to get Andy and the children ready to say goodbye”

We would all take a slow walk to the beach and have a swim, go out and eat together, hang out by the pool, catch up with friends and go to a movie. We got to just be for a while. As each day passed after chemo, Andy was able to do simple things like pushing Indi on a swing or lifting her up into a tree. For the first time I understood what being present was and we enjoyed every moment.

On New Year’s Eve, we all went to a friend’s apartment and watched the fireworks over Sydney harbour. As the exhilarating display exploded over the water, we happily bid farewell to 2010. Andy and I snuggled on the sofa. He had his arm around me and he became reflective about the year behind us. “In some ways, this has been the best year of my life,” he said. Andy had to go for a scan in mid- January. He was feeling really good; he’d recovered well from chemo. It felt like we might just be able to pull off a miracle. But it wasn’t to be. The scan showed the cancer had come back with gusto. “What we are dealing with is an absolutely aggressive and nonresponsive cancer,” said our doctor.

We were both shattered, absolutely devastated. Andy’s death became a real possibility. Some days I’d get in the shower, turn on the taps and cry. I’d been having these visions of his funeral. So many scenarios flooded into my mind. I’d think, “How’s it going to be for Jesse at school without a dad?” I knew it was wrong of me to even think about Andy dying, and that in itself would make me cry, but there I’d be, sobbing my heart out as the water washed over me. The shower was the only place I could let it all go. The thing that changed for me was the realisation that he might not make it. Time was running out. Unwittingly I stopped worrying about things. The breakdowns in the shower stopped, and I became calm and present. I wanted to be with Andy and not be scared anymore.

In May, we planned a weekend away with the kids and friends in Kangaroo Valley, two hours south of Sydney. We rented a beautiful house with views over rolling hills. That weekend was so special. Andy took his guitar and the boys had jamming sessions, we ate beautiful food and relaxed as a family for the first time in ages. Six weeks beforehand we’d thought Andy would soon be dead. “I’m not going to let cancer rule our lives,” Andy said. It became all about “how to live with cancer” as opposed to “how to die with cancer”.

But by June, the pain had begun to creep back into his system. Andy could barely walk. My friend Kiki came around one morning and we decided to take Andy to his favourite cafe. There were three flights of stairs from our apartment to ground level and as I turned to close the door, all I could hear was a dreadful thumping sound. Andy had fallen down the stairs. On the first step his leg had given way and he had no feeling at all in his left leg.

Kiki and I helped Andy to the car as he did his best to keep his cool and not panic that his leg no longer worked. Then I raced back upstairs and grabbed a bag of his things and we drove straight to the hospice in Darlinghurst. I thought about the tattoos Andy and I had got a year earlier and the relevance of what the words, Be here now, really meant. Five weeks later, I lay next to Andy all night and stroked his face. It was an extraordinary process to facilitate someone letting go of their life.

The most challenging hurdle for me was getting Andy and the children ready to say goodbye. We brought the children to the family room at the hospice. There was a whiteboard and I had drawn pictures of Andy asleep next to a cloud, with a smiling pussycat and the sun and the stars above him. I told them Daddy’s body was broken and that we could no longer fix it. I said that soon he would need to go to sleep, and that once he went to sleep it would be so deep that he would never wake up, and this was called dying. Jesse began to cry. “But I don’t want Daddy to go,” he protested. “I know darling, and nor do I,” I said, while giving him a gentle hug.

“The kids helped shave Andy’s head. They took his hair and made pretend moustaches”

We took Jesse and Indi into Andy’s room and they climbed up onto the bed with him. Andy had lost weight and his bones were very angular, but his hair had grown back and he was peaceful. When he heard the kids, he sat up and rallied himself. He hugged them and in a gentle, reassuring voice said, “I am going to go to heaven soon. I have to go to heaven because my body is really broken. It’s like a butterfly when one of its wings is broken, it can’t fly anymore. But don’t worry, because I’m going to go up into the sky and every time you look up you’ll see me.” It was a very beautiful moment and I was in awe of how he was able to muster the strength one last time for those two precious babies, so they could say goodbye to their daddy.

I realised there was no life or death anymore, it was all about right now. I lay down on the bed next to Andy and laid my hand on his chest. It was really peaceful and suddenly it was very quiet and I leaned in to his ear and said, “You can go now, Andy, it’s OK.” It was strange because literally there was nothing left in him, but all of a sudden he made a noise and out of the blue somehow he managed to mumble a sound that was like, “Love you”. And then he exhaled a long breath and he was gone.

I just stayed there. I sobbed into his chest, but it felt like Iwas releasing him, too. This shell of a body was there, but Andy was gone. I’d lost my best friend, my lover, my husband – the person who taught me about life, death and everything in between. Life sometimes throws us a curveball that we never anticipated and instinctively we duck for cover to avoid its erratic and unpredictable trajectory, when the most empowering move to make is to challenge ourselves to leave past and future out of the moment and step bravely into its path, staring it down. My experience of this kind of surrender occurred in the time leading to Andy’s departure, as I like to call it, and in my being able to lie next to my hilarious, silly, brave and beautiful best friend as he exhaled his last breath.

Fast-forward five years and here I am, now a solo mummy and sole breadwinner. Losing Andy taught me to sit solidly in the middle of life’s ups and- downs and to embrace, and even love, the ordinary parts of life as much as the extraordinary peaks. Each and every moment, from the bruised knees to the love of a lifetime, deserves the reflection and acknowledgement that leaves you open to life’s gifts.

Spartacus and Me: Life, Love and Everything In between