Sweat glistening on his naked torso, the young man moved like lightening across the ring. He was almost a blur as he danced from side to side, swaying like a windscreen wiper. Suddenly his opponent saw his chance and punched him so hard his gloved fist seemed to disappear into his body. Stunned, the man looked as if he was about to fall to his knees, then he started to jab, punching relentlessly, raining down blows until he saw the blood begin to flow.

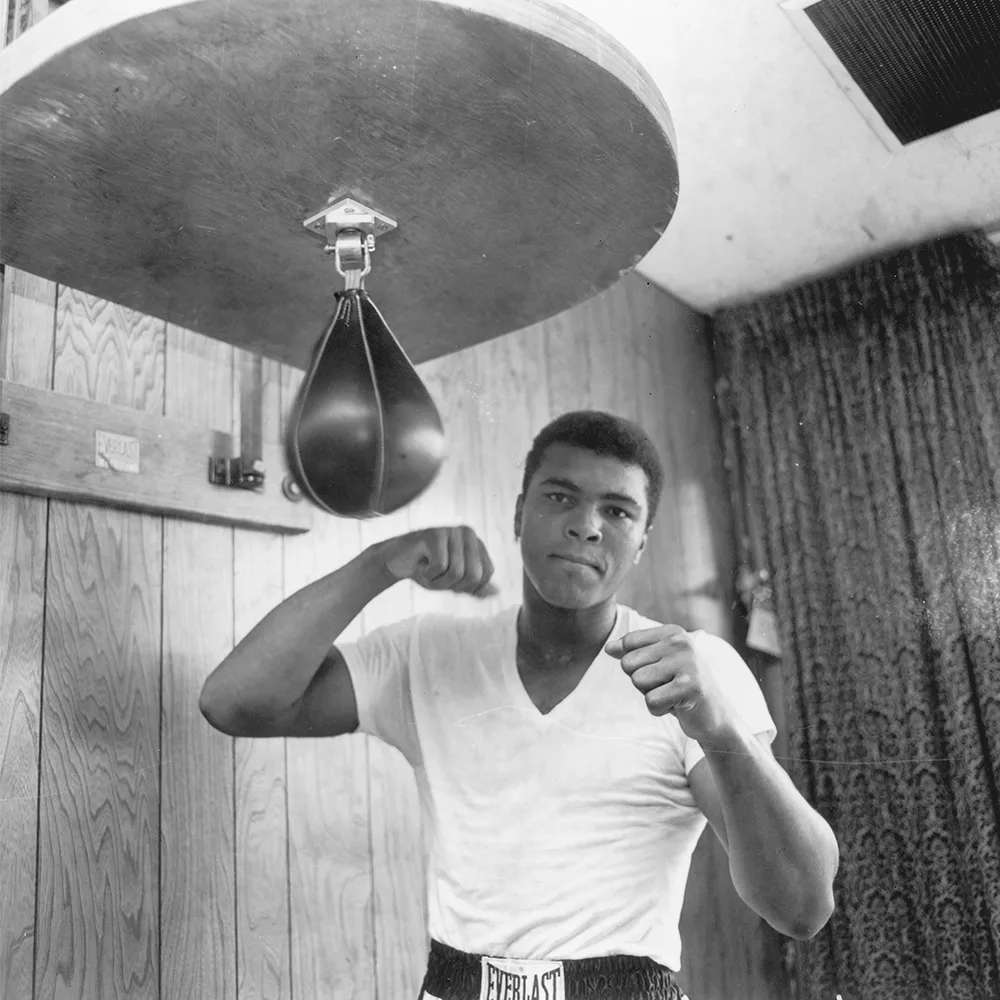

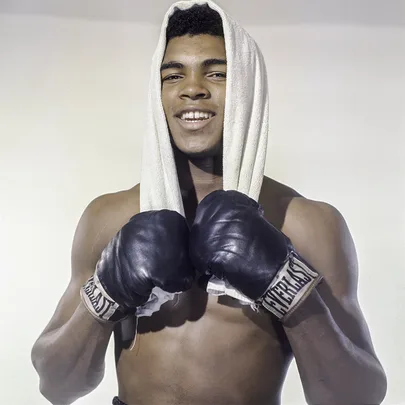

On February 25, 1964, a month after turning 22, Muhammad Ali became heavyweight champion of the world when he defeated opponent Sonny Liston. Lifting his hands triumphantly in the air, he almost levitated around the ring as he shouted to the crowd, “I am the greatest! I am king of the world!” It was the start of an incredible career that would see Ali win 56 out of his 61 fights, including 35 knockouts, and be crowned champion three times. The world had never seen a boxer like him. Devastatingly handsome, he brought style, grace and a totally new kind of fighting to the ring. He was fast on his feet, and he used his speed to outpace his opponents and avoid their fists. When his own knockout punch came, they never saw it coming. His showmanship was unique. He wrote poetry predicting the outcome of his fights (‘If you talk jive, you’ll fall in five’), coined legendary catchphrases like, “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” and created his own dance move, The Ali Shuffle. As he once said, “It’s hard to be humble when you’re as great as I am.”

But as Ali discovered, the great have a long way to fall. He became one of the most hated men in America when he joined the Nation of Islam, also known as ‘The Black Muslims’, and refused to be inducted into the US army to fight in Vietnam. Branded a draft dodger, he was stripped of his heavyweight title and banned from boxing. Ali’s career had been KO’d just as he was in his prime, and it would be three and a half years before he would be allowed back into the ring. When he was, his heroic return was one of the greatest comebacks of all time, and turned Ali into even more of a sporting legend.

Born on January 17, 1942, Cassius Marcellus Clay Junior grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, with his parents Cassius Senior and Odessa and younger brother Rudolph. At 12, Clay’s bicycle was stolen and when he reported it to the local policeman and boxing coach, he was given his first lesson in the ring. Hooked, he returned home and announced to his family that one day he would be champion of the world. He started running before school and trained for hours in the gym when lessons were over. By the time he graduated from high school he’d fought over 100 amateur bouts and won six major boxing championships, including an gold medal at the Rome Olympics. He would later claim in his 1975 autobiography The Greatest: My Own Story, that he threw his medal into the Ohio River after being refused service in a white-only restaurant – and so was given a replacement medal at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics when he lit the torch.

Despite the fact he never excelled at school, Clay was a skilled orator from the start, creating an outlandish aura to PR his fights. “I am the greatest, I can’t be beat. I’m the fastest thing on two feet!” he’d boast to the press, who nicknamed him ‘Gaseous Cassius’ and the ‘Louisville Lip’. Being handsome also helped. Author Toni Morrison called him ‘a beautiful warrior’ and when a writer for Harper’s Bazaar watched him fight, she gushed, “He was simply to die for’. It was all part of his strategy. “I called my opponents names and boasted of my abilities and beauty, and often predicted the round of my victory, to infuriate them so they would make mistakes,” he said. “Some may call this a trick. I just hoped it gave me an edge.” He used it to devastating effect for his first title fight against Sonny Liston in 1964. Turning up at his home to hurl insults and taunts, he continued his psychological warfare at the pre-fight weigh-in by shouting, screaming and pretending to go crazy to “needle him and work on his nerves so bad that I would have him beat before he ever got in the ring with me.”

It worked and became a defining moment for the young Cassius Clay. A month later he declared he’d joined the controversial Nation of Islam, headed by Malcolm X and announced that from this point on he would no longer by known by his old ‘slave’ name and would be called Muhammad Ali instead. It did not sit well with journalists or the public, especially when Ali began making statements such as calling the white man ‘the devil’ and anti-integration sentiments. His new faith was also at odds with the woman he’d married on August 14, 1964, a month after they’d been introduced. Cocktail waitress Sonji Roi wore short skirts and refused to wear the Muslim veil, and Ali admitted he’d once tried to forcibly remove her make-up and had slapped her during an argument. He filed for an annulment less than a year after their wedding, claiming: “She wouldn’t do what she was supposed to do.” Post-divorce, however, he turned into such a womanizer that he was dubbed the ‘pelvic missionary’ by his physician Ferdie Pacheco. “When Muhammad went back to women he did it with world records in mind,” he said.

Ali still had plenty of energy left for the ring. He beat Sonny Liston in a rematch, finished off Britain’s Henry Cooper in six rounds and left Cleveland Williams ‘spitting blood’. That night, said one sporting commentator, Ali was “the most devastating fighter who ever lived. He had a combination of size and speed that had never been seen in a figher before”. But Ali’s reign was about to come to an abrupt end. In April 1967, after refusing to be indicted into the US military and fight in Vietnam, Ali was unceremoniously stripped of his heavyweight title and his boxing licence suspended. Exiled from the sport he loved and the only jobhe’d ever really had, Ali opened a restaurant called Champ Burgers, lectured on the college circuit and briefly starred in a Broadway musical, Buck White. He also married Belinda Boyd, who he met at a Muslim convention, and fathered four children – daughter Maryum, twins Rasheeda and Jamilla, and son Muhammad Junior.

Three and a half years later, with support for the Vietnam war waning, America was ready to take Ali back and the courts re-instated his boxing license. On March 8, 1971, New York’s Madison Square Garden was packed to capacity as celebrities like Diana Ross and Dustin Hoffman poured in to watch Ali versus Joe Frazier in the biggest event in boxing history. Burt Lancaster was in the commentary box and Frank Sinatra sneaked into the press section at the front, where he ended up taking the cover shot for Life magazine. Ali was in fighting spirit. “There’s not a man alive who can whup me,” he shouted at the crowd. “‘I’m too fast. I’m too smart. I’m too pretty. I should be a postage stamp. That’s the only way I’ll ever get licked.” For all his rhetoric, Ali lost that night, but defeat made him more determined than ever to win back his title, in the most spectacular fight the world had ever seen.

The Rumble In The Jungle took place on October 20, 1974 in Kinshasa, Zaire – now the Democratic Republic of Congo. Promoter Don King’s first professional event, he controversially arranged to fund $5million prize money, thanks to the flamboyant Mobutu Sese Seko, president of the impoverished nation. Opponent George Foreman was the favourite against the ageing Ali, but with the searing heat hitting 100 degrees Fahrenheit, Ali commanded the crowd to chant ‘Ali Boma Ye!’ (‘Ali, kill him!’) and knocked out Foreman in the eighth round. “Now that I got my championship back,” said Ali later, “every day is something special.”

But there was another old score to settle. For months tension had been building between Ali and Frazier and when Ali called him ignorant and a gorilla, their animosity escalated. “I don’t want to knock him out. I want to take his heart out,” raged Frazier. By the time they finally came face to face again in the Thrilla in Manila in October 1975 their hatred for each other was palpable. The fight, also promoted by Don King was billed as the clash of titans and a confident Ali enraged the tough Frazier by not training as much as he could have and stating his opponent was over the hill. “It’ll be a chilla, and a killa, and a thrilla, when I get the gorilla in Manila,” he famously taunted. The fight was bloody, going all 15 rounds until Frazier’s trainer refused to allow him to continue. “The fight was truly brutal,” said Ali in his 2004 autobiography The Soul of a Butterfly (Bantam Books), famously saying, “This must be what death feels like,” and congratulating Frazier for his courage. “Of all the men I fought in boxing, the roughest and toughest was Joe Frazier,” said Ali. “He brought out the best in me, and the best fight we fought was in Manila.”

“Before [that last fight], I could never really say goodbye to boxing, so boxing said goodbye to me”

Muhammad Ali

But that wasn’t the only fight Ali had in Manila. During his marriage to Belinda there had been many affairs, during which he had fathered two children, and for the past year his mistress had been Veronica Porche, who he met after she won a contest to be a poster girl for his fights. His long-suffering wife had always turned a blind eye to the other women, but when she saw Ali and Veronica on public engagements in the Philippines, it was the final straw. Catching a plane out from Chicago, she stormed into his hotel room and confronting her errant husband hurled abuse and furniture before heading straight back home again. At a press conference the following day, an unrepentant Ali announced: “I know celebrities don’t have privacy. But at least they should be able to sleep with who they want…” A year after their divorce, on June 19, 1977, Ali married Veronica and they went on to have two daughters, Hana and Laila.

By 35, Ali was a shadow of the boxer he used to be. Before his exile, his speed in the ring meant he rarely got hit. With that now gone, Ali adopted a new strategy – the Rope-a-Dope – where he would lay against the ropes taking punch after punch until his opponent was too tired to dole out any more and he had chance to hit back. The first sign this new tactic was failing came when Ali lost to a novice fighter, Leon Spinks, in February 1978. “I was lousy,” admitted Ali, who put himself through a gruelling training regime to regain his world heavyweight title from Spinks that September. But it was a luck lustre fight, and the following year Ali announced his retirement. Just twelve months later, he was back. “Muhammad was never happy outside the ring,” said his trainer Angelo Dundee. “He loved boxing. It was in his blood, and win or lose, he loved it to the end.” The fight against Larry Holmes was stopped in the 10th round. It was “like watching an autopsy on a man who’s still alive”, said fan Sylvester Stallone. And on December 11, 1981, Ali entered the ring for the last time, losing to boxer Trevor Berbick. “Before that point, I could never really say goodbye to boxing, so boxing said goodbye to me,” said Ali.

For many years, there had been concerns about Ali’s health, and in 1982 he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. His marriage was also deteriorating and he and Veronica divorced in the summer of 1986. In November he married childhood friend and fellow Muslim, Lonnie Williams, and the couple adopted a baby son, Assad. Despite his condition, during his retirement, Ali spent much of his time travelling around the world for humanitarian causes, while at home on his farm in Arizona, he was a familiar face in the neighbourhood. “He’s the only man I know where the kids come to the gate and say, “Can Muhammad come out and play?”’ said his assistant Kim Forburger. With the passing years, his health slowly deteriorated and it was an emotional moment when the world watched Ali, hands trembling, light the torch at the Olympic Games in Atlanta in 1996. But although he now walks with a white frame and his slurred speech often makes it difficult to understand him, ‘Mighty Mouth’ can still talk the talk.

“In the history of the world from the beginning of time, there’s never been another fighter like me,” Ali once boasted, and in his last autobiography the master of self-publicity was still at it. Thinking about how he’d like to be remembered, he wrote: “I’d settle for being remembered as a great boxer… And I wouldn’t even mind if folks forgot how pretty I was.”

Getty

Getty