It all started with two words: me too. On October 15 last year, actress Alyssa Milano shared a simple idea on Twitter in support of her friend Rose McGowan’s allegations of sexual abuse against movie mogul Harvey Weinstein. “If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me too’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”

The response was overwhelming; the post was retweeted 24,000 times and it received 67,000 comments. Women from around the world united in solidarity and shared their personal experiences in 140 characters or less.

The stories were devastating and painfully relatable: “Me too, I never told anyone because I thought it was my fault for sending the wrong signals”; “Me too, he was my stepfather”; and “Me too, you never get over it. You just learn to live with it.”

Celebrities including Lady Gaga, Debra Messing and Evan Rachel Wood were among the first stars to add their voices to the Me Too movement.

The outpouring flowed from social media into the real world; women swapped stories over coffee, HR departments reviewed their sexual harassment policies and inquiries were launched. Both online and off, the world is a very different place to what it was a year ago. Here’s how…

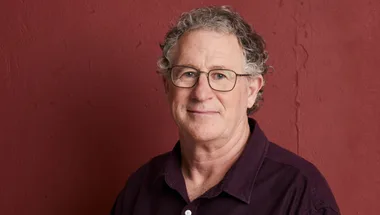

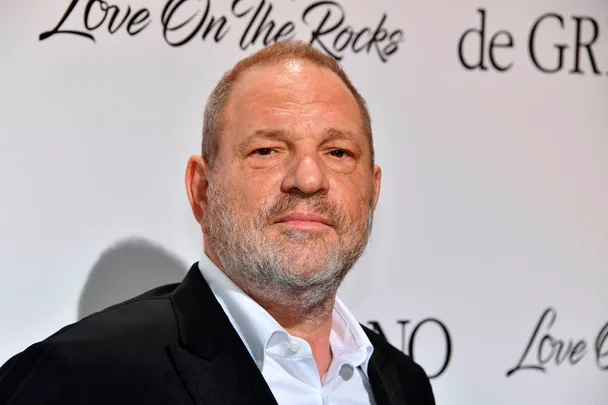

WEINSTEIN’S DOWNFALL

On October 5, The New York Times published an article in which actress Ashley Judd recounted an incident she’d had with Harvey Weinstein. Two decades before, the film producer had invited Judd to the Peninsula Beverly Hills hotel for what she thought was a business breakfast meeting. Instead, she was ushered to Weinstein’s hotel room where he appeared in a bathrobe and asked her to watch him shower.

Judd wasn’t the only young actress in Hollywood who Weinstein harassed with his hotel-bathrobe routine. In the months after The New York Times exposé and a subsequent report in The New Yorker, more than 75 women have opened up about their sickening experiences with Weinstein. Rose McGowan, Salma Hayek, Gwyneth Paltrow and Angelina Jolie came forward with allegations ranging from sexual harassment to rape.

On October 8, Weinstein was fired from The Weinstein Company. Two days later, his wife Georgina Chapman left him. On May 25 this year, New York police charged him with “rape, a criminal sex act, sex abuse and sexual misconduct for incidents involving two separate women”. A third criminal sex assault case has since been brought against him and further charges are expected to follow. Weinstein has pleaded not guilty to all charges and has denied any allegation of non-consensual sex.

THE CHAIN REACTION

The Weinstein revelations have had a domino effect on the entertainment industry. High-profile men in Hollywood including actors James Franco, Kevin Spacey, Jeffrey Tambor, Ed Westwick and Jeremy Piven, TV host Matt Lauer and comedian Louis C.K. have all been accused of sexual misconduct. Many of them, including Spacey, Tambor and Lauer, have been fired from hit shows as a result. It’s been said that there’s never been a worse time to be a white guy in Hollywood. The same goes for a select few in Australia…

In late November, TV gardener Don Burke was accused of sexually harassing a string of female colleagues throughout his career in a Sydney Morning Herald piece that described him as a “high-grade, twisted abuser”.

In January, actor Craig McLachlan was accused of indecent assault and sexual harassment on the set of the Rocky Horror Show musical. Actresses Christie Whelan Browne, Angela Scundi and Erika Heynatz gave accounts of McLachlan’s allegedly lewd behaviour on and off the stage, including the time he is said to have traced the outline of Whelan Browne’s vagina during a performance.

McLachlan has denied the claims and is suing Whelan Browne, Fairfax Media and the ABC for defamation.

More than 1600 people in the media shared their Me Too stories with journalist Tracey Spicer after she posted a callout on Twitter in October.

“My Twitter inbox is burgeoning with horror: rape, digital penetration, poking, groping, grabbing,” she wrote eight months later in The Saturday Paper. Spicer, along with 30 high-profile women including Deborah Mailman, Sarah Blasko and Danielle Cormack, launched the NOW Australia campaign and raised $120,000 to help women who have experienced sexual harassment in the workforce.

THE FASHION FALLOUT

In the wake of Weinstein-gate, American model Cameron Russell started the Instagram hashtag #MyJobShouldNotIncludeAbuse to share horrific allegations of abuse in the fashion industry. “There are many Weinsteins in our industry, they aren’t hard to spot. If you know one, act now. Don’t wait for 30 years for a New York Times exposé,” she wrote. The fashion world listened. In the past year, designers, models, stylists, photographers and publishers have all shone a light on misconduct.

One of the most vocal advocates has been the Instagram account @ShitModelMgmt, which started naming and shaming alleged abusers in February.

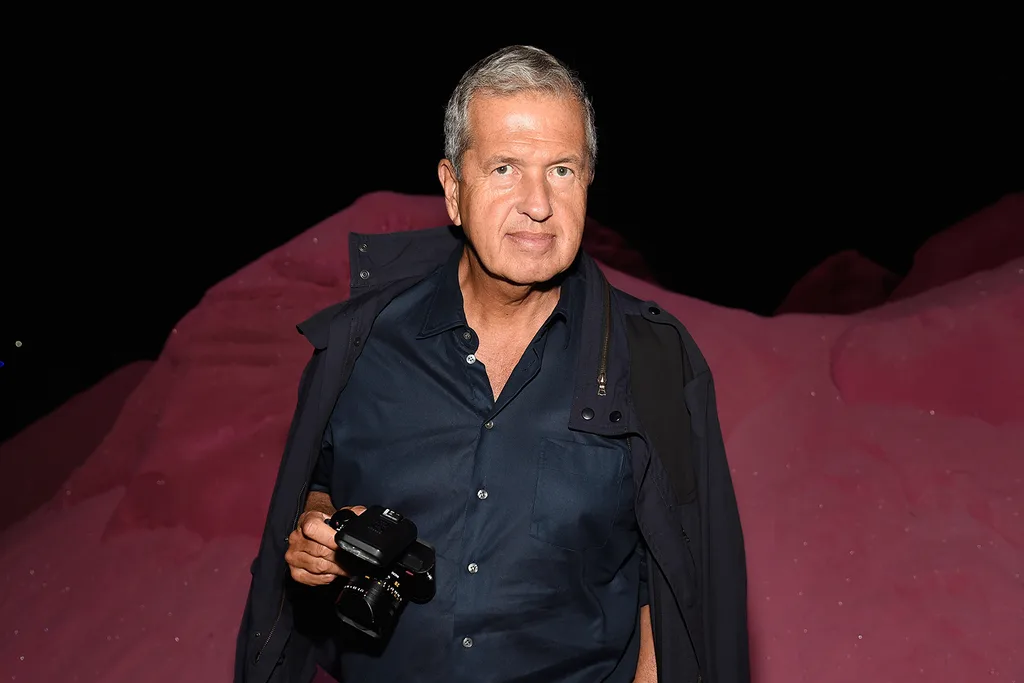

Two of the people named in the blacklist were acclaimed photographers Mario Testino and Bruce Weber, who were later accused of sexual exploitation by nearly 30 male models and assistants in a New York Times report. Subsequently, publishing giant Condé Nast released a statement saying, “We are deeply disturbed by these accusations and take this very seriously. In light of these allegations, we will not be commissioning any new work with Bruce Weber and Mario Testino for the foreseeable future.”

The brand also suspended its relationships with photographer Patrick Demarchelier after more than 50 men and women came forward with allegations, and Terry Richardson, who has a long history of alleged abuse. Advocacy organisation The Model Alliance has started drafting a code of conduct and has called upon brands, agencies and media companies to sign the legally binding agreement to protect those at risk of abuse

FACING THE MUSIC

At the Grammy Awards in January, American singer Kesha was joined onstage by women including Cyndi Lauper and Camila Cabello to perform her anthemic ballad “Praying”.

Wearing all white, the women belted out Kesha’s song about the abuse she allegedly suffered at the hands of her former producer Dr Luke, singing, “I’m proud of who I am, no more monsters, I can breathe again.” The moment of solidarity was hailed as the night’s most powerful performance.

Hundreds of women in the Australian music industry have also united with the hashtag #meNOmore. In an open letter signed by high-profile singers Courtney Barnett, Tina Arena and Isabella Manfredi of The Preatures, the group shared anonymous stories of sexual harassment in the industry.

One woman recalled an incident when she was working backstage for a huge international act, revealing, “Their tour manager looked me in the eyes as he told the room there were only two types of women: bitches and sluts.”

Since the open letter, there have been changes in Australia; festivals have started increasing the number of women on their bills, performers such as Drake have called out audience members for groping, and venues have cancelled gigs of alleged abusers.

THE NEW RULES OF DATING

A 2016 study by Consumers’ Research found that 39 per cent of American online daters had felt harassed on Tinder; unsurprisingly, women were much more likely to have experienced harassment than men.

Since Me Too, the pressure is growing in the industry to shift the power from miscreant men to the women who call them out. Blocking and reporting functions are no longer enough.

In May, Bumble, the dating app where only women can make the first move, wrote an open letter to a college swimmer called Dylan after he sent a female user abusive messages. Bumble described his language as “hateful, body-shaming, misogynistic, toxic and violent”. The letter went on: “You’re blocked, banned, and will never be welcome on our platform again.”

It’s not just the apps: women themselves are feeling empowered to hit back in innovative ways. The artist Anna Gensler makes naked sketches of men who’ve sent her crude messages, and posts them on Instagram (@instagranniepants). Blogger Samantha Mawdsley replied to an unsolicited penis pic with a catalogue of photos of male genitalia. And on the Instagram account @ByeFelipe, a woman who was asked for a nude photo claims to have sent a close-up of Gordon Ramsay’s forehead wrinkles, which she was passing off as her cleavage.

AT WORK

Me Too has touched every corner of the workforce, and each industry has reacted differently. In March, a group of 180 female CEOs launched Time’s Up Advertising to address the industry’s pervasive problems with gender inequality. In Silicon Valley, the tech industry started a Me Too platform on an app called Blind, where women can anonymously share stories. Also in the US, the National Science Foundation issued new guidelines stating that sexual harassment was not tolerated in the scientific community. In academia, university staff and students launched the hashtag #MeTooPhD to share their experience of sexism, unwanted sexual advances and lewd comments.

In parliament, Australian politician Sarah Hanson-Young filed a defamation suit against Senator David Leyonhjelm after he told her to “stop shagging men” in a debate about women’s safety. Hanson-Young said she received a “flood of messages from women who have experienced sexual harassment in their workplaces”.

This article originally appeared in the October issue of marie claire.

Getty

Getty