Over the last six months, Hong Kong has been brought to its knees by what has become the city’s biggest political crisis of modern times. Instead of the bustling global hub the city was previously known as, Hong Kong has become home to an increasingly bloody warzone.

To understand why the protests have come about, a brief recap on Hong Kong’s history is required. Hong Kong was a British colony for 150 years and was returned to China in 1997. Under the principle of “one country, two systems,” it was agreed Hong Kong would have a high degree of autonomy (except in foreign and defence affairs) for 50 years.

As a result, today Hong Kong has its own legal system and borders as well as rights not seen on mainland China such as freedom of assembly and freedom of speech.

Although most people in Hong Kong are ethnic Chinese, the majority do not identify as Chinese. According to surveys conducted by the University of Hong Kong, most Hong Kong citizens identify themselves as “Hong Kongers” and just 11 per cent identify as Chinese.

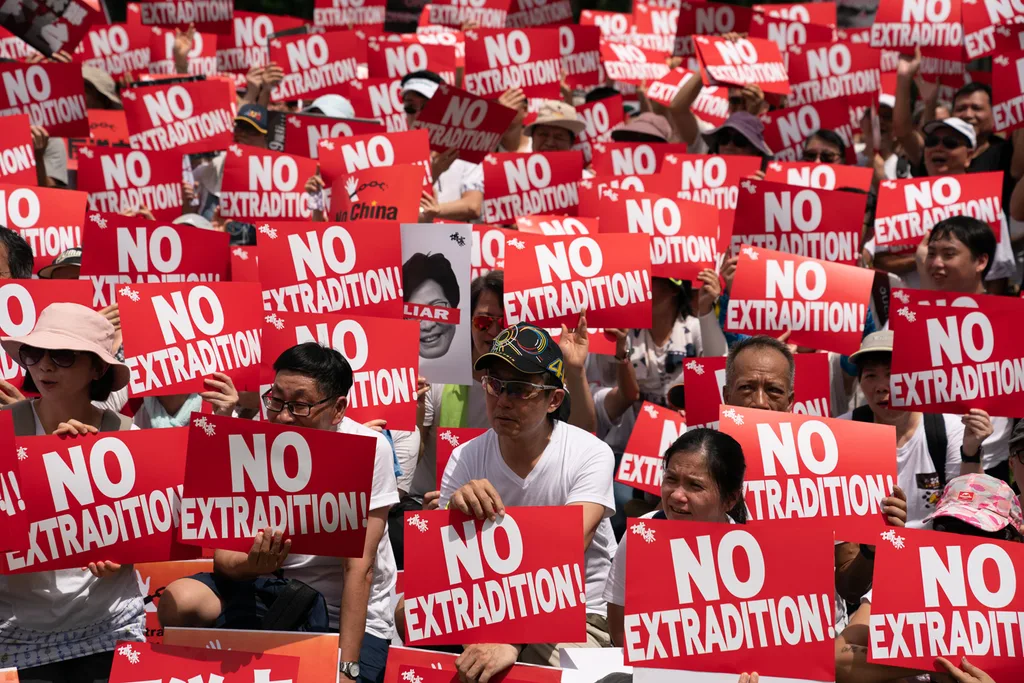

Following the proposal of a controversial extradition bill in March 2019, what initially began as a peaceful demonstration became a wider pro-democracy movement when Hong Kong citizens saw their rights being threatened. The situation has now descended into a violent war between protestors and police.

China’s leaders have painted protestors as dangerous separatists with Chinese president Xi Jinping warning any attempt to divide China would end in “bodies smashed and bones ground to powder”.

Meanwhile, on the streets of Hong Kong, violence has become the new norm.

So, how did we get here?

The murder that started it all

The catalyst for the introduction of the extradition bill was Hong Kong citizen, Chan Tang-kai, who was accused of murdering his girlfriend in Taiwan. Following the alleged murder, Chan fled back to Hong Kong where he was convicted of money laundering by a Hong Kong court, in relation to the murder of his girlfriend, Poon Hiu-wing.

However, as for the actual murder charge, Hong Kong authorities ran into a catch 22: Chan could not be charged with the murder in Hong Kong as the crime had occurred in Taiwan; and authorities were unable to extradite him to face a murder charge in Taiwan because Hong Kong does not have an extradition agreement Taiwan.

Thus, the Hong Kong government used the case to support their proposal for a controversial bill to allow such criminal extraditions to countries and regions not currently covered by Hong Kong’s extradition treaties.

The significance of the extradition bill

The extradition bill was unveiled in April 2019 and was quickly condemned by critics who believed the proposed changes would undermine the judicial independence of Hong Kong, and leave Hong Kong citizens vulnerable to China’s strict legal system. Critics have argued China’s legal system to be deeply flawed and have raised concerns that if Hong Kong citizens were to be extradited to China, they could face detentions, trumped-up charges, and unfair trials resulting in wrongful convictions.

Following the protests, the Hong Kong government formally withdrew the bill on 23 October however demonstrations have continued with protestors claiming the withdrawal was “too little, too late.”

Why did the protests turn violent?

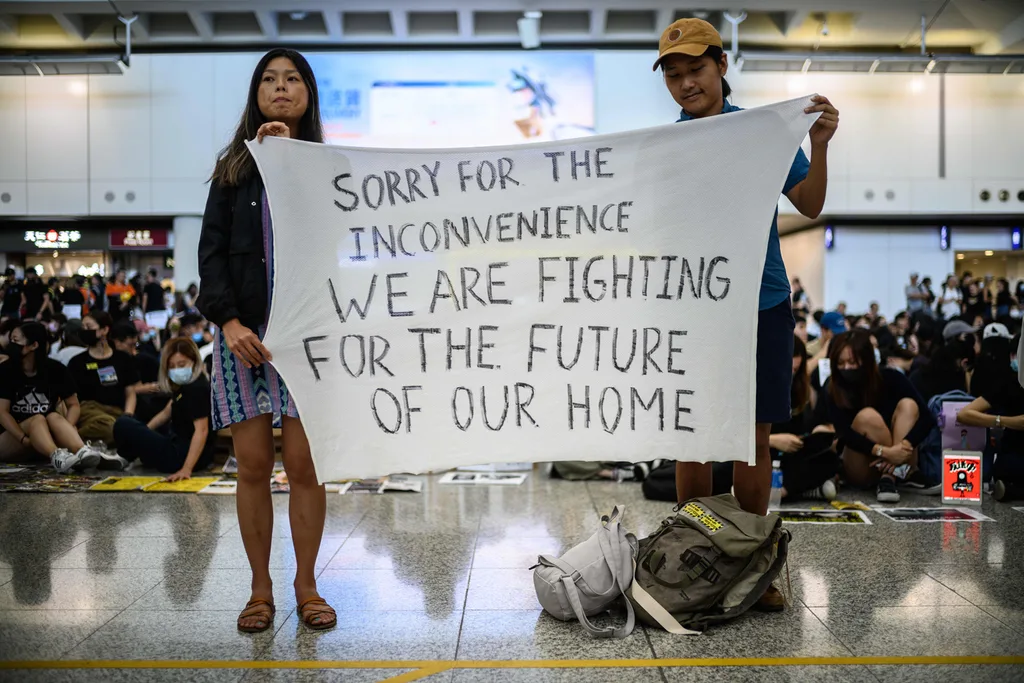

Prior to the extradition bill’s second reading in the Legislative Council on 12 June, police fired rubber bullets and used tear gas on protestors including young, unprotected persons. This provoked other citizens of Hong Kong to turn out in protest and from there, the situation has escalated with protestors storming Hong Kong’s parliament, taking over the transit system, and bringing business at the airport to a halt.

Following the upsurge of the protests, bloodshed ensued. In October, an 18-year-old protestor was shot at close range and killed by police. On other occasions, a protestor fell to his death while trying to evade tear gas from police, a pro-Bejing lawmaker was stabbed to death by a person pretending to be a supporter, and a local councillor had his ear bitten off while trying to stop a knife attack.

What do protestors want?

Initially, protestors campaigned to simply have the bill withdrawn but during the two-months it took Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam to formally withdraw the bill from the government’s agenda, protestor’s grievances grew and the list of demands expanded to five.

Many protestors adopted the slogan “five demands, not one less,” with the remaining four demands being: the withdrawal of the categorisation of the early protests as “riots,”; amnesty for arrested protesters; an independent inquiry into alleged police brutality; and implementation of complete universal suffrage in Hong Kong.

Although the extradition bill has now been fully withdrawn, protests continue based on the remaining four demands. There have also been widespread calls for the resignation of Carrie Lam, with many accusing her of being a puppet to Beijing.

What’s happening now?

Protests continue with the latest battleground being Polytechnic University where protestors have been holed-in by police since Sunday evening following a day of violent clashes in the area. In dramatic scenes, groups of protestors have attempted to escape by leaping from ropes strung from the building and fleeing with the assistance of waiting motorcyclists. Others have not been so lucky and have met teargas, rubber bullets, a water cannon, and police arrest. In a desperate attempt to escape, some activists were arrested after emerging from sewage drains.

So far, police have detained around 1,000 protestors from Polytechnic University including 300 minors.

As Hong Kong’s political crisis deepens, Hong Kong’s police have been criticised for their handling of the protests with Human rights group Amnesty International describing the police tactics as “reckless and indiscriminate.”

Meanwhile, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet told a media conference the level of violence associated with the protests warranted an “effective, prompt, independent and impartial investigation.”

In September, Hong Kong’s Independent Police Complaints Council appointed a panel of five experts on police tactics from the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada to help provide advice on its practices and procedures. But, the panel has found the council inadequately equipped to do the job and have said it must be furnished with greater powers to properly carry out the investigation.

As both the government and protestors are showing no signs of backing down, it is unclear where the situation will conclude.

Over the last six months, Hong Kong has been brought to its knees by what has become the city’s biggest political crisis of modern times. Instead of the bustling global hub the city was previously known as, Hong Kong has become home to an increasingly bloody warzone.

Over the last six months, Hong Kong has been brought to its knees by what has become the city’s biggest political crisis of modern times. Instead of the bustling global hub the city was previously known as, Hong Kong has become home to an increasingly bloody warzone.