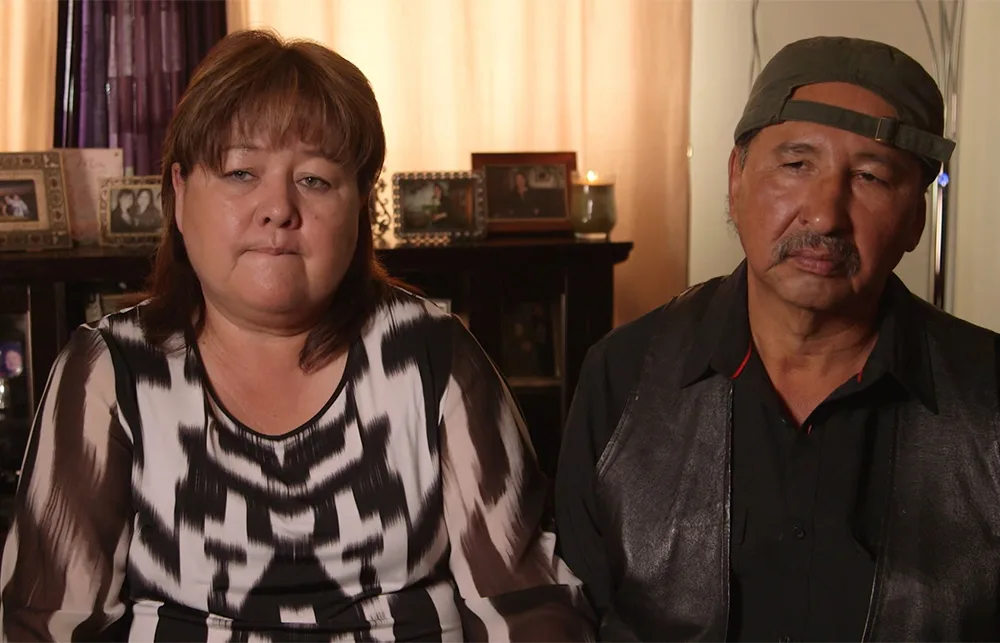

Every summer when the snow thaws, the family of missing Indigenous teenager Jennifer Catcheway begin their search in Manitoba, Canada, for her remains.

Dressed in high-vis and with the help of an excavator, the Catcheway family sift through rubbish and debris in search for bones—likely all that remains of Jennifer—who vanished at age 18, nine years ago.

The heartbreaking moment is documented in the latest installment of SBS’ Dateline, ‘Vanished: Canada’s Missing Women’, which examines the country’s starling number of Indigenous women who are victims of violence.

“Each year Jennifer’s parent’s dig up a different area, they bring in anyone who will help them, usually family members, and they have search dogs,” Dateline reporter Laura Murphy-Oates tells marie claire over the phone in Sydney.

“They’re still physically searching for their daughter that they lost nine years ago.”

Murphy-Oates explains that Jennifer’s father, Wilfred, has also dedicated his days and nights to investigating her 2008 disappearance. He estimates he has interviewed 1000 people to date—in the absence of a satisfying police lead.

“Wilfred’s whole life has been consumed by this case,” Murphy-Oates says.

“He’s got thousands of interviews on his camera and hand-held recorder; he goes around interviewing people trying to figure out what happened to his daughter. They haven’t figured out how exactly she went missing and how she was most likely murdered.”

Jennifer is one of many of Indigenous Canadian women who have disappeared or been a victim of violence. A 2014 police report found that nearly 1200 Indigenous women were missing or murdered in the country between 1980-2012. Indigenous women also report rates of violence 3.5 higher than non-Aboriginal women.

For the Dateline investigation, Murphy-Oates and her documentary team met with Manitoban law enforcement, politicians, and numerous families in First Nation, a community with one of the highest numbers of unsolved missing and murdered indigenous women in Canada.

“There I spoke to 10-15 different people, probably even more, who had lost not even one loved one, but multiple in their family and friends,” Murphy-Oates recounts.

“One woman had lost three immediate family members to violence and I did get very personally affected by it.”

Murphy-Oates believes Australia has a lot to learn from Canada’s response to missing and murdered women.

In 2015, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.

“Canada’s launched this national inquiry, which was kind of a long time coming, advocates were pushing for it for decades. It seems that Australia in general maybe hasn’t quite woken up to the levels of violence or connected the dots the way Canada has,” the reporter explains.

“We do have the conversation about domestic violence that’s been happening in the last couple of years. It’s great that we’re having that conversation, but I don’t know whether Indigenous people are being spoken about in this conversation enough.”

So does Australia need a similar inquiry to Canada?

“Whether we need something like a national inquiry like Canada, I don’t know but I know it will definitely help people realise the specific reasons why violence is happening in Indigenous conditions, which as in Canada, is part of this societal breakdown that’s come from things like the Stolen Generation and from colonisation,” Murphy-Oates says.

“It has left this legacy of trauma and broken families and communities—and that all feeds into violence against Indigenous women.”

Watch the full report – Vanished: Canada’s Missing Women on Dateline, Tuesday 21 November at 9.30pm on SBS.

Bernice Catcheway

Bernice Catcheway