At the age 15, Noni Och had no reason the presume she was unsafe as she sat playing a video game in her cosy bedroom adorned with posters. But as she navigated further into the globally popular World of Warcraft, she began to feel increasingly uncomfortable.

Using voice chat to communicate, Och hoped to swap tactics with other players. But when it became apparent that she was the only female in the arena, things took a nasty turn. She felt the hairs on the back of her neck prick up as the men began to gang up and intimidate her with a series of invasive questions.

“What are you wearing?” “How old are you?” “Are you legal?” After she stopped responding, their aggression increased. Then, one of them told her he was masturbating. “He started moaning and calling my name,” she says. “I felt like I was going to be sick.”

Shaking, she left the voice chat and closed the game. “I didn’t play for a long time after that,” admits Och, now 21. “I was too ashamed to tell anyone about it. I blamed myself.”

The demographics of video game culture have changed dramatically since the 1980s and ’90s. It is no longer an area dominated by young men – in fact, the Entertainment Software Association in the US estimates that, although numbers fluctuate from year to year, women have made up about half of gamers globally since 2014.

But despite women now representing a significant stake in what has become a multi-billion-dollar industry, the last decade has seen gaming become notorious for sexism, sexual harassment and trolling.

It’s an issue that has remained largely unchanged for years. A 2012 US study found 80 per cent of gamers think sexism is rampant in the gaming community and revealed that 63 per cent of women had been called c**t, bitch, slut or whore while gaming.

Och, who studied game development at the Academy of Interactive Entertainment in Sydney and now works as an indie game developer, believes the overt sexualisation of female characters and the normalisation of violence against women is at the basis of the issue.

“As long as female characters have been featured in gaming, they have been depicted as sex objects with huge boobs and tiny waists,” she says. “In combat games they have skimpy bikini armour that wouldn’t serve any purpose. I think it affects how men treat women in gaming – they see women as property for them to abuse or harass.”

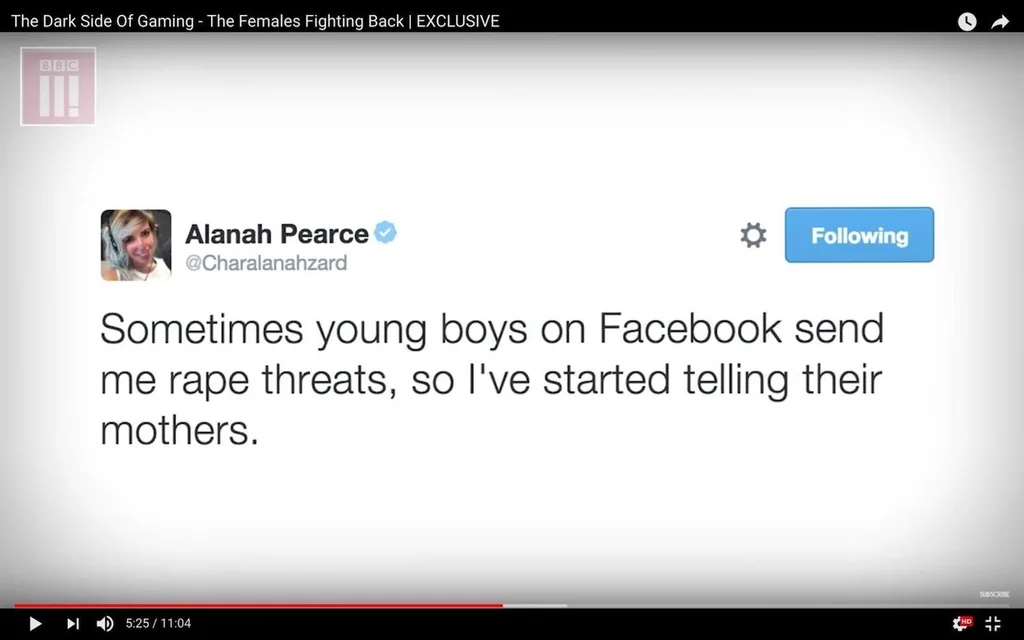

And while the #MeToo movement has encouraged thousands of women from a diverse range of industries to publicly speak out about sexual abuse and harassment, the gaming community has remained conspicuously quiet. But a handful of women in prominent gaming roles are now speaking up, finally paving the way for some much-needed change.

American behavioural scientist and virtual reality (VR) tech expert Jessica Outlaw is one of them.

In April, she published the results of a study into women’s experiences in VR spaces, finding that almost 50 per cent of women who have engaged with VR have been sexually harassed. This encapsulates stalking and groping of the avatar and verbal harassment via voice chat. The numbers did not surprise her. “I think that it’s under-reported and I believe the actual number is much higher,” she says.

Outlaw is a part of the statistic: earlier this year she was abused in a VR social space while conducting a business meeting (a practice becoming increasingly popular in tech circles). Within five minutes, a male avatar insinuated she was having sex with her colleague. “He asked my colleague – a man I’d only met twice before – if he had a ‘green dick’ because my avatar was green,” she recalls. “It was humiliating on a professional level.”

On another occasion, a male avatar slapped Outlaw’s avatar across the face, an experience that created a disturbing impact in her real life. “I had intrusive memories of it for days,” she explains.

Ally McLean experienced everything from casual sexism to full-blown misogyny as one of Australia’s first professional cosplayers, the term given to people employed by gaming companies to dress up as video game characters and bring them to life.

“When working in cosplay I was often treated like I wasn’t even a real person – I was groped, hit on and harassed,” says McLean, who is now a passionate advocate for women in games. “Being a woman cosplaying even a vaguely sexualised character really exposed me to the rampant misogyny in the industry. I don’t think those men would treat me the same way now that I have a voice in the industry, but it doesn’t mean they aren’t still doing it to others.”

Having moved from cosplay into game development, McLean soon discovered the tech side of the industry to be just as chauvinist. “I’ve had male executives personally admonish me in creative roles for bringing up ‘women’s issues’ such as sexual harassment or representation in relation to game narratives,” she reveals.

Women are dramatically under-represented in the Australian games industry. Of the 928 people currently employed by gaming development studios, only 19 per cent identify as female. To really shift gaming culture, this imbalance needs to be addressed.

McLean has identified one way to improve the status quo. As director of The Working Lunch, she aims to empower young women who are trying to break into gaming by connecting them with other female mentors who are established in the industry. “Our goal is to eradicate … being the only woman in the room,” she says.

Another important step is getting more school-aged girls into STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects. “We need to show them that game development is a real career option,” McLean explains. Part of this will be ensuring that game developers consider representation when designing new characters. “I think that needs to continue; young girls need to see themselves represented in games, as do people of colour, as do non-binary people, as do LGBTQI people, as do disabled people – we have a long way to go.”

It’s hoped greater female representation in the industry will have an impact on the everyday experiences of the women and girls who participate in gaming as consumers. But that won’t happen overnight. In the meantime, having better tools to report abusive users is crucial.

In 2012, US media critic Anita Sarkeesian launched a Kickstarter campaign to crowdfund Tropes vs. Women in Video Games, a video series that examined the way female characters are over-sexualised and reduced to stereotypes. “Women shouldn’t be disposable objects or symbolic pawns in stories about men,” she said at the time.

The backlash was swift and vicious. A cyber mob descended on Sarkeesian’s social media accounts and flooded them with hateful and sexist comments, death and rape threats. A game in which players could beat her up was circulated. She even received bomb threats. Her residential address was made public and she was forced to flee her home.

When Gamergate – a harassment campaign that targeted women in gaming and the influence of feminism on video game culture – started in 2014, Sarkeesian received more abuse.

The campaign claimed to be about “ethics in video games journalism”, however the scale of abuse directed at women told a very different story. At the peak of the campaign, more than two million tweets had been sent.

For women who work in the gaming industry, the risk of another Gamergate-style hate campaign is ever-present. Experts such as Outlaw say this is why the gaming industry hasn’t had a #MeToo moment. “I know a woman at a very prominent company in the gaming and VR industry who told me that she thinks about Gamergate every time she posts on social media,” she says.

Leena van Deventer, an award-winning game developer, writer and lecturer at RMIT, wrote about the Gamergate controversy in her book, Game Changers: From Minecraft to Misogyny. “I wanted to talk about online harassment and Gamergate because I saw it hurting friends of mine, and I felt it was important to put it on the public record,” she tells marie claire.

“Women are reluctant to talk about sexual harassment in games or online because they fear the mob will come after them.”

Jennifer Wadella is a JavaScript developer and co-founder of fatuglyorslutty.com, a website that was set up to capture the harassment aimed at female gamers (the name is the sum of the “go-to” slurs thrown at women and girls online). Women would screenshot messages and submit them to the website, where they’d be published under categories including “crudely creative”, “death threats” and “unprovoked rage”. The aim was to laugh at the type of men who abuse female gamers, because “sometimes that’s all you can do”, and also to make men think twice about sending sexually-explicit death threats.

The site is now on the backburner, having gone some way to raise awareness about the problem, and Wadella says taking a stance helped to create change in the industry. “I know several companies, including Bungie and Microsoft, that took notice of the harassment we documented and made changes to their platforms. I think the industry as a whole has really stepped up and given attention to the issue,” she says. Yet despite improvement in recent years, there is still a severe lack of female protagonists in games, as well as an over-sexualisation of female avatars.

Och believes the gaming giants can go much further to make the environment more inclusive and safer for women. Yet to achieve long-term, sustainable change, Och says men across all platforms of gaming need to step up and say something. “It’s all very well for men to say, ‘I don’t harass women’, but if it’s happening in front of them and they’re not saying anything, then they’re complicit. If you’re [a man] in a space with other men and they’re harassing or belittling women, call it out,” Och adds.

It has been six years since Och’s first encounter with sexual harassment in an online game. Does it still occur? “All the time,” she says flatly. “There are two different types: it’s either, ‘You’re a girl and you have to prove that you’re as good as the guys,’ [or] there’s the more sexual sort of hitting on you or being gross.”

Male peers often tell Och that females are simply too sensitive about the issue and need to toughen up. But she is fierce in her assertion that girls and women should be able to play games without worrying about men being “creepy”. “I’ve worked with young girls at [international educational company] Girls Make Games and some of them already have stories,” she reveals. “It’s heartbreaking. No kid should have to worry about being humiliated or seen as lesser just because they’re a girl.”

But Och is determined and ready to fight back. Change might be slow, but it’s definitely coming, she says. “We’re not going anywhere.”

GET SUPPORT:

1800RESPECT

Telephone and online counselling for victims of sexual harassment. 1800respect.org.au; 1800 737 732

THE WORKING LUNCH

Mentoring for women in games. workinglunch.online

WOMEN IN GAMING AUSTRALASIA

Dedicated to empowering women who work in gaming or want to work in gaming. wga.org.au

GAMER WOMEN

A platform dedicated to women who game. (Forums coming soon.) gamerwomen.com