In early 2022, two Saudi sisters were living in a large, modern apartment block in the Sydney suburb of Canterbury when word spread within the building that they may be in some sort of trouble.

Asra and Amaal Alsehli, who had left Saudi Arabia and arrived in Australia in 2017 seeking asylum, had moved into a two-bedroom apartment in the block, and had kept mostly to themselves. But after a water leak in the building, a plumber went to the women’s flat, where he later reported there was “something weird going on”, according to a source inside the building.

It was a “vibe” he got that there was “something wrong”, and he refused to return.

Concerned for the women’s safety, two building-management employees visited the sisters, who reluctantly opened the door. The source, who spoke to marie claire on condition of anonymity, said the apartment was messy, with clothes strewn about like a teen’s bedroom, but nothing appeared out of the ordinary.

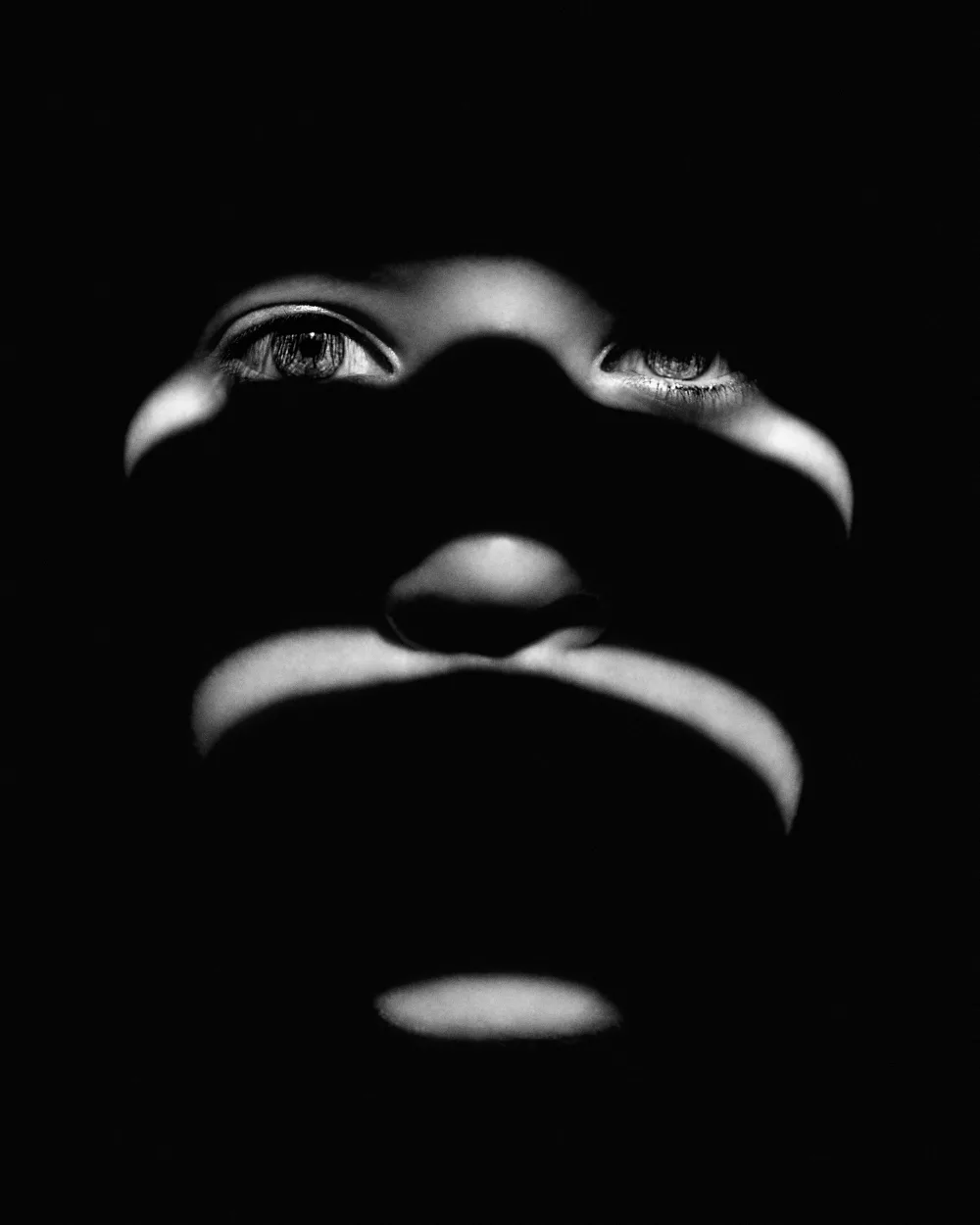

What was odd was the demeanour of the women, who retreated to the balcony entrance; Asra, 24, stood by the door and Amaal, 23, huddled next to her on a chair. They were wide-eyed, looking “scared shitless”, said the source. The visitors asked if they were OK.

“Yes,” they said. “If you’ve got a problem, you should tell us. Do you need help?” “No,” they said.

Three months later, the women were found dead in their beds. In a tragedy that has confounded authorities and thrown a spotlight on the extreme hardships faced by Saudi women both in and out of their country, the women’s badly decomposed bodies were discovered in their separate bedrooms on June 7, 2022, more than a month after they had died.

Despite post-mortem exams, a cause of death was not reported to the police at the time, leading the chief investigator to call the deaths “suspicious”, a label that does not preclude the possibility of a double suicide.

“The girls were 23 and 24 and have died together in their home,” said Detective Inspector Claudia Allcroft in July. “It’s unusual because of their age and the nature of the matter.”

The matter extends far beyond the walls of the Sydney apartment. The women had fled their homeland and its oppressive laws against women, which raised red flags for the press and inspired some pointed questions at a police media conference that July: “Are any of the family members suspects?”; “Is the fact that the girls fled Saudi Arabia a line of inquiry?”; “Is it possible the girls were murdered?”

Allcroft poured water on all the queries: “The family are assisting police,” she said. “There’s nothing to suggest that [they are suspects].”

While there is scant detail of the women’s lives before they left Saudi Arabia, a kingdom with an authoritarian government headed by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, it is understood they came to Australia as teenagers six years ago. According to at least one person who met them, the sisters had fled their homeland seeking a life free of oppression.

Though the Islamic nation, which adheres to Sharia law, has claimed to have eased some of its oppressive policies in recent years, women still come under male guardianship laws. These require women to seek permission from a male relative – father, brother, husband, cousin – to leave the home, including for travel, education and employment. Those who flee can face extreme retaliation from the government and their “shamed” families, according to Human Rights Watch.

Asra and Amaal had reportedly applied for permanent protection visas in Australia based on the fact that one was gay and the other an atheist. Homosexual acts and renouncing Islam are both illegal in Saudi Arabia, punishable by death.

The sisters’ first-known address was in Smithfield, in Sydney’s west, where they rented a basement granny flat. A female occupant of that home told the ABC the “nice” women studied traffic management at TAFE and worked as traffic controllers for a construction company. Each registered an ABN as sole traders in 2018.

And according to the woman, Asra had a “boyfriend” at the time and later applied for an apprehended violence order against him, but it was withdrawn in 2019. The man was not a Saudi.

The next year, they moved to the Canterbury building, renting a two-bedroom flat on the first floor. “They were very quiet,” said a former resident, who asked not to be named.

But they spoke up to building management over several concerns: their BMW being damaged in the car park, and the belief a food delivery was “tampered with”.

By early 2022, they appeared to be venturing out more, attending a “girls-only queer event”, according to The Guardian. A woman who spoke to them there said they told her that gay people lived in “fear” in Saudi Arabia. “They said they were grateful to be living in Australia,” the woman said.

At the time of the plumber’s visit a few weeks later in March, the behaviour of the sisters was concerning enough for police to be called for a welfare check. The women “appeared fine”, said Allcroft.

But after they fell behind in their rent payments, NSW Sheriff’s officers entered the property on June 7 and found the women’s rotting bodies with no visible signs of trauma. There was no evidence of a break-in. Investigators believe they died in early May and the autopsies reportedly found toxins in their body that pointed to suicide, a police source speculated to Sky News. The case is now with the NSW Coroner. (NSW Police declined to comment to marie claire.)

For many residents of the building, the shock of the deaths, coupled with the lack of information provided by authorities, was too much to bear. “We got letters, but there was no information on anything,” Amy Gonsalves, a former resident, tells marie claire. “I moved out because of the deaths.”

When UK human-rights lawyer Toby Cadman first heard of the tragedy, it struck him as suspicious. In 2019, Cadman was instrumental in securing asylum for another pair of Saudi sisters who were fleeing their country in similar circumstances. Dua and Dalal al-Showaiki, aged 22 and 20, escaped their family while on holiday in Turkey, and used the media to highlight their plight.

“In Saudi Arabia we were forced to live our lives according to our male guardians,” the sisters said in a statement.

Dua, who is gay, faced extreme hardship in her homeland, says Cadman, a London-based international law specialist. “She was being forced into marrying an older man,” he told marie claire. “And both women had gone through physical and sexual abuse over a number of years.”

Through the UN, Cadman negotiated a route for the sisters to an undisclosed country. “All they really wanted to do was lead a normal life – go to university, study,” says Cadman. “The last conversation I had with them, they were safe, well and happy.

The degree to which families push for that outcome depends on their influence. In the case of the al-Showaiki sisters, Cadman says they came from a family of considerable influence. “The sisters’ brother had come to Turkey to find them,” he says. “He was using the Saudi consulate in Istanbul to try to

get them back home. But the Turkish stood up to the consulate.

“It’s very dangerous for these young women,” Cadman emphasises. “As we saw in Turkey, there are Saudi families who try to use Saudi intelligence to nab these girls and bring them back.”

It is not suggested that Amaal and Asra’s family, who are reportedly also influential, were engaged in such a plot, but marie claire has learnt that the women reported to building management that a man was “acting strange” outside the apartment complex. CCTV footage confirmed the presence of a man, but not his intent. They also claimed that “a private investigator was following them”, a source associated with a legal service accessed by the women told the ABC.

Further, the sisters had applied for protection visas, which The Australian reported were denied by the Department of Home Affairs (DHA), due to a lack of detail in the applications. Still, they appeared to be on amicable terms with their mother, who reportedly visited the sisters while they were living in Smithfield.

While the DHA does not discuss individual cases, a spokesperson told marie claire that its method is consistent with the approach adopted by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Ten Saudi females were granted permanent protection visas in Australia during the past year (between June 2022 and May 2023) and fewer than 10 were refused such visas. “Australia will prioritise those cohorts who have the greatest resettlement need,” said the spokesperson.

But for advocates such as Daniela Gavshon, the Australian director of Human Rights Watch, the plight of Saudi women is unique and should be treated as such by governments.

“Despite some reforms made in Saudi Arabia, the government continues to implement the male guardianship system … leaving them at grave risk of domestic violence,” Gavshon tells marie claire.

Those reforms have included lifting a ban on female drivers in 2018, but experts argue that oppression remains. “I’ve had contact with a Saudi woman in her early thirties who was not married so she came under the control of her father,” says Cadman. “She was subjected to the most awful beatings.”

If such women escape, “abusive men and families can track down women who flee, so it’s critical countries provide the support and protection needed by these women”, Gavshon says.

It is believed Asra and Amaal accessed some support services in Sydney. Margherita Basile, who runs the Sydney Women’s Counselling Centre near Canterbury, says the sisters had received assistance at a women’s health centre. (The centre declined to comment.) But overall, Basile says, “There is a distinct lack of appropriate services to meet the demand.”

How much support the sisters received (and needed) will be one of the aspects of the case examined by the coroner. At press time, the findings were not expected for “many months”, said a NSW Courts spokesperson.

“It did strike me as highly suspicious. You have these two young girls who, as terrified as they were, were starting to have a normal life,” says Cadman. “Or maybe they were so terrified of being taken back to Saudi Arabia that they took their own lives. Having tasted freedom, maybe it was just too much for them to handle.”

If this story raises concerns, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or beyondblue.org.au.