An outpouring of allegations from Australian gymnasts has exposed a culture of systemic abuse in the Olympic sport. After decades of neglect, athletes all over the world are demanding to be heard.

In 2006, at the age of 15, Queensland gymnast Chloe Sims (now Gilliland, pictured above right with her teammates at the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne) stunned the world by winning two gold medals – team and individual – with her electrifying routines at the Melbourne Commonwealth Games. But then, at 17, she found herself at breaking point. After two years of battling bulimia and anxiety, of being called “heavy” and “stupid” by coaches every day, “I felt it was easier to end my own life than to give in to what they wanted me to be,” says Gilliland. Fellow Commonwealth Games gold medallist Alex Eade was only 12 when she started hearing the same sort of comments.

“I was overseas competing and I’d fallen off the bars,” she remembers. “My coach yelled at me and said it was because my bum was too heavy.” Away from her family or anyone who could comfort her, the scared little girl steeled her jaw, blinked back tears and carried on. “It’s not like I could go home and cry to my mum,” she says. “So you just kept quiet and kept going.”

Body shaming was part of Eade’s everyday existence until she left the sport in 2019, aged 21. And the abuse wasn’t limited to verbal slurs. The talented child – and then young woman – who just wanted to fly and tumble and twist for the pure joy of it, felt like she was slowly crushed, both mentally and physically, as she climbed the ranks of the sport she loved. “There was a specific competition in 2018 that was the worst,” she says. “We were trained to exhaustion, for 16 days in a row. We were starved. We were told we would never be good enough, that we were an embarrassment to our country. The ridiculous training load meant I sustained an injury to my Achilles but coaches told me I was lying about it to get out of training, so I competed on it. It’s like we were animals that were disposable.”

The anger and hurt still evident in her voice, Eade describes how she was constantly called stupid. “That felt so personal. It wasn’t even about my gymnastics. It was about who I was as a person. I remember calling my mum and asking, ‘Mum? Am I fat and stupid?’ It got so you didn’t know what to believe any more.”

Gilliland and Eade’s stories are shocking. But what makes it even more so is that their accounts appear to be anything but unusual.

All over Australia and across the world, former and current gymnasts of all ages, ranks and levels are bravely coming forward with detailed experiences of alleged abuse, exposing an entrenched toxic culture within the sport.

The outpouring has been sparked by the Netflix documentary Athlete A, which details the crimes committed by former USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar. In 2018, he was sentenced to 40–175 years in prison for sexually assaulting gymnasts in his care. (More than 150 women gave testimony; he pleaded guilty to abusing seven girls.) He was already serving a 60-year sentence for unrelated child pornography charges, meaning he will be in prison for a minimum of 100 years.

It wasn’t just Nassar’s convictions that resonated with so many young girls and women who had grown up in gymnastics the world over. The documentary’s depiction of a culture of control, compliance and humiliation was also painfully familiar.

“Emotional and physical abuse was the norm,” Jennifer Sey, the 1986 US national champion and one of Athlete A’s co-producers, says in the film. Cruelty, she explains, was considered the best way to create docile, compliant gymnasts who would do whatever was asked of them in order to be the best. “We were so beaten down and made so obedient that when we knew there was a sexual abuser in our midst, we would never say anything. We were powerless.”

While Eade says she never experienced sexual abuse during her time in the sport, she related – with a traumatic jolt – to the toxic culture that enabled Nassar to horrifically exploit the situation to his benefit. marie claire acknowledges that those crimes are in a very different category to the behaviour described by Gilliland and Eade.

For Eade, and the many young athletes like her, the humiliation and physical torment that she’d always thought was an accepted part of her sport suddenly had a new and extremely confronting name. “It made me realise that what I was experiencing wasn’t normal,” she says. “Before watching it, I’d never have put this label on the treatment that I was receiving at the time. It was abuse.”

Shortly after the film’s June release, Australian gymnasts began sharing their stories under the hashtag #GymnastAllianceAus. Their posts had three stark things in common: near identical stories documenting the appalling treatment they allege they suffered, from very young ages, during their gymnastics careers. A shared sense of fear and anxiety for coming forward. And lastly, an overwhelming compulsion to demand change on behalf of the girls who would come after them.

“I am scared to share my story, but at some point someone has to stand up for the athletes,” Mary-Anne Monckton (pictured above), who represented Australia at three world championships, wrote on her Instagram page. “I, like so many others, have experienced body shaming, have had food withheld … and been manipulated and ‘forced’ to do things that I was not physically ready for or capable of doing, which ultimately led to career ending injuries,” she wrote. “The abuse (physical, mental and emotional) needs to stop, or at least be stamped out of our sport.”

Livia Giles (née Gluchowska, pictured above), now 35, previously competed in rhythmic gymnastics at an elite level in both Poland and Australia, and says she experienced abuse in both countries. She remembers being paraded in front of her Polish teammates when she was eight while her coach told the other girls in her class to call her “Fatso”. She weighed 24kg.

Stieve De Lance claims that her 12-year-old daughter, Trinity (pictured above), who still trains at local clubs in Victoria, was pushed to keep performing a gruelling exercise so many times during one training session that she chipped her spine. “I was crying and saying, ‘My back hurts, please can I stop?’ and was on the floor rocking in pain,” says Trinity. She says she was forced to keep training.

Emma Pinder (pictured above), who trained 32 hours a week at a Queensland club when she was only six years old, remembers hiding her tears after being pushed to the brink, knowing crying was considered an unforgivable weakness.

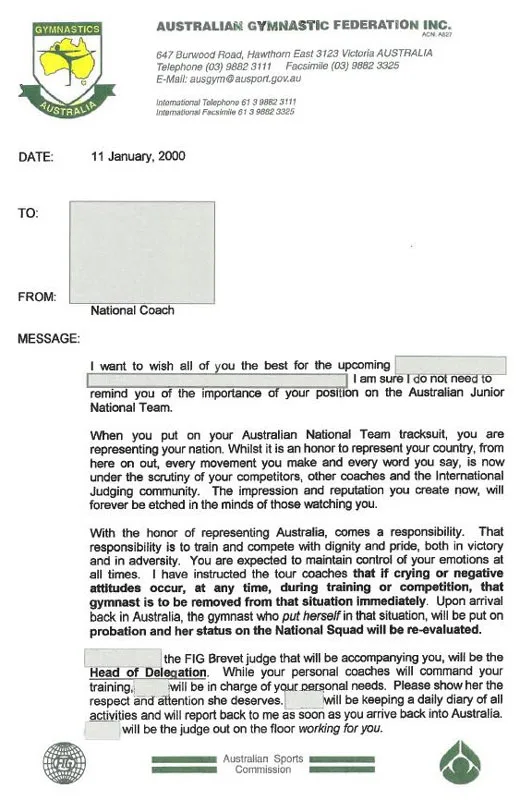

marie claire has sighted a document (pictured below) from a Gymnastics Australia coach sent to elite junior athletes representing Australia in 2000 that states: “if crying … [occurs] at any time, during training … the gymnast who put herself in that situation, will be put on probation and her status on the National Squad will be re-evaluated.”

The threat worked, says Pinder. “You learnt to cry in the hallway so the coaches didn’t see,” she explains. “Then you’d cry in the car going home in the dark so no-one would notice. Then you’d cry in the shower after training. And then you’d stop feeling anything anymore and you’d just zone out.”

As the allegations against the sport gained traction on social media, many gymnasts were concerned that sport’s national governing body would zone out, too. But just a few days after the online reckoning began, Gymnastics Australia CEO Kitty Chiller posted a video on Instagram and released a written statement with the same message. “This is a challenging time in our sport in so many ways,” she began, before explaining that a new hotline would allow athletes to anonymously report their stories to the organisation. “We have and will always have zero tolerance to any form of abuse toward any member, especially those vulnerable younger members of our community.”

Lawyer Adair Donaldson greeted this development with deep scepticism. Having worked with victims of systemic abuse within other traditionally opaque organisations, such as the Australian Defence Force, he now represents around 40 former and current gymnasts who are coming forward with their stories. His goal is to help them agitate for real and lasting change in the sport.

“Quite frankly, the time for listening groups or reflection is over,” Donaldson tells marie claire, adding that Chiller’s assertion that Gymnastics Australia has never tolerated abuse is factually unsupported. Two inquiries into Australian gymnastics – in 1995 and 2018 (Donaldson did not work on these) – led nowhere, he says, despite documentation almost identical to the current allegations. “They were supposed to be watershed moments and they weren’t.”

The 1995 inquiry into Women’s Artistic Gymnastics at the Australian Institute of Sport – a 361 page document – makes for particularly appalling reading. Allegations of smacking and hitting of young girls were dismissed as unreliable recollections of children too young to know what they had witnessed or experienced, or found not to be physically painful enough to do any damage. In the end, only a small handful of specifi c instances of physical abuse were found to be true, and one coach was ordered to undertake “counselling” before he could return to his position. But the report concluded that “no systemic or widespread abuse of AIS female gymnasts has been found to occur at any time” and that “major change is not necessary”.

A week after her initial video, Chiller released a second statement announcing Gymnastics Australia had engaged the Australian Human Rights Commission to undertake another independent review into the sport, with fi ndings to be handed down in early 2021. Donaldson and the women he represents welcomed it with caution. “The people we’re acting for have no faith in Gymnastics Australia,” he says. “What concerns me is that it will be a rush job. We have at least 40 years of issues and histories that need to be considered.”

He is encouraged that the inquiry will be led by Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins, who has a strong track record identifying and recommending changes to protect women in male-dominated industries and workplaces, but hopes she is given the necessary scope required. “We want a disciplined deep dive, and an enquiry that is robust enough to address these systemic failings,” he says. “The proof will be in the pudding.”

When marie claire asked Gymnastics Australia whether they would commit to implementing the commission’s recommendations at the conclusion of the inquiry, they declined to respond.

Some of the gymnasts still have a semblance of positivity for the sport that once dominated every moment of their young lives. “It definitely taught me a lot about goal setting and working hard,” says Giles. Eade says her Commonwealth gold medal was a triumph she will cherish forever. “I feel a sense of pride, knowing I could endure what I did – injuries and abuse – and still achieve my dream.”

But each is still struggling with the damaging aftermath. Eade is studying medicine, but still suffers from crippling self-doubt, certain that she won’t be good enough to make it. Giles says she sometimes lies awake at night remembering having her body grabbed to indicate how “fat” it was. Pinder has a voice in her head that tells her to restrict food, and the medals and trophies she won have either been thrown away or hidden. “There’s something about them that doesn’t sit right with me,” she says.

Going forward, each of them wants something from the sport that they consider more precious than any medal: accountability and change. “Until we start seeing action, this abuse will continue to riddle the sport,” Eade says. “The reason I and so many others have spoken up is so current and future athletes don’t have to suffer the way we did.”

This report originally appeared in the October 2020 Issue of marie claire.