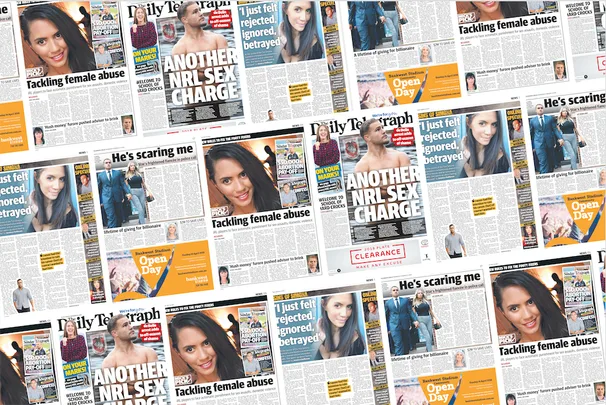

Following a sordid off- season, the NRL has lost sponsors, fans and respect. As insiders describe a boys’ club culture of bad behaviour, Michael Crooks speaks with the women who have suffered the most, and are now fighting back.

She had only been with her boyfriend for a few months, so when Jaya Taki learnt she was pregnant, it was an emotionally overwhelming day for the 29-year-old. In those first heady hours in her Sydney home, feelings of shock, disbelief and anxiety could be suddenly off set by bursts of exhilaration and joy as she tried to wrap her head around what four home pregnancy tests confirmed after she missed her period. She picked up her phone and texted the news to a close friend, her fingers quivering on the screen’s keyboard. The friend was thrilled, even congratulating her, and Taki began to wonder what she was ever fretting about. Happiness began to take over, and she was suddenly looking ahead to a bright, new horizon.

Now she was even eager to tell her boyfriend, but that had to wait. He was at work at ANZ Stadium, an elite footballer in Australia’s beloved National Rugby League. Taki, a health therapist, had met the Wests Tigers’ centre Tim Simona through social media, and over four months of dating and “hanging out”, they had forged a dreamy bond. That day was game day at the Tigers’ home ground, which for Simona, not only meant chasing a Steeden across a hallowed paddock for 80 minutes. but an after-game function for the fans. By the time Taki messaged him to call her it was late into that March 2016 evening.

“He called and I told him I was pregnant,” Taki tells marie claire. “And within one minute he said, ‘Well, you know exactly what we’re doing.’ And I said, ‘What?’ And he said, ‘We’re not keeping the baby.’”

It marked the beginning of a tortuous period of what Taki calls emotional and psychological abuse that would lead to a heart-rending abortion, the destruction of a relationship and the end of a celebrated career. Hers is one of the many disturbing stories of NRL players emotionally, physically or sexually abusing women. In a sordid and shameful 2018-2019 off-season for the code, five NRL players were charged over assaults against women, including alleged domestic violence attacks.

The incidents came as no surprise to Taki, who says such conduct is at the heart of the insular boys’ club culture of the NRL, where women are routinely objectified and used, and appalling behavior is often ignored within a win-at-all-cost mindset. “I was so traumatised by my relationship [that] I told the NRL,” she says. “I told them I had gone to the police, telling them he had been threatening me. They did nothing. The way they treated me was despicable.”

In the beginning, Taki, who hails from Christchurch, was wary of dating Simona. The 27-year-old had reached out to Taki on Facebook (they had mutual friends) and a quick scroll down his page revealed he was a famous footballer from Auckland. Taki, who runs her own colonic clinic, had previously had a relationship with a NRL player with whom she shares a daughter, Rydah, and was aware of the pitfalls of dating a professional footballer.

“I was cautious,” she explains. “But Tim was completely amazing. He was so kind and thoughtful, everything you want from someone. Within a couple of months I was thinking it’s the greatest thing that’s ever happened to me.”

His lifestyle wasn’t bad either. “He got free meals, free club entry, he didn’t pay for anything,” says Taki. “People were always stopping him for photos.”

Before she told Simona she was pregnant, Taki had resolved to raise the baby, a sibling for then four-year-old Rydah. In her mind, the baby was unplanned, not unwanted. But for Simona, it was unwanted and Taki said he refused to accept she would have the baby without him. “He was heartless,” explains Taki. “When I sent him a message that I wanted to keep the baby, he messaged back, ‘I just vomited.’” Another text, which she saved, read, “Knowing that I have a kid running around will haunt me for the rest of my life.”

It was emotional blackmail, says Taki. “He said, ‘You will ruin my life, how could you do this to me?’ And you start to think, ‘I really love this guy, I don’t want him to feel that way.’ I didn’t want to do anything wrong by him. God forbid he will hate me.”

Suffering from a debilitating morning sickness that left her “weakened”, she agreed to a termination. “He came with me,” she says. “I said after- wards, ‘You made sure I did it, didn’t you?’ Next day he went out clubbing.”

The day after the abortion, Taki returned to work to keep busy. The next day, a Sunday, was Rydah’s fifth birthday. On Monday, “I woke up like a truck had slammed into me and I was like, ‘What have I done?’ I was burning with anger and sadness.”

She learnt there was a form of domestic abuse known as abortion coercion (also called reproductive coercion) that was a common factor of many terminations. “People said, ‘He didn’t force you to have an abortion,’” she says. “But they don’t understand emotional domestic violence, the manipulation.”

When people began hearing her story, “I started to get a lot of messages from other women who had been in the same situation involving NRL players,” she says. “I heard stories of broken wrists, abuse, coerced into abortion – and the NRL did nothing about it.”

For years, the NRL has been plagued by accounts of domestic abuse and violence, mistreatment of women, sexual assaults and group rape – including the infamous Coffs Harbour incident in 2004, in which a 20-year-old woman accused as many as six Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs players of gang raping her at a resort (no charges were laid).

Since November last year, four NRL players – Jarryd Hayne, Zane Mus- grove, Liam Coleman and Jack de Belin – have been charged over sexual offences involving women. All men maintain their innocence. And Manly Warringah Sea Eagles player Dylan Walker and North Queensland Cowboys’ Ben Barba were also involved in separate alleged domestic violence attacks (see The Sin-Bin overleaf).

Adding to the NRL’s woes was the circulation on social media of multiple sex videos involving NRL players, including the Bulldogs’ Dylan Napa and Penrith Panthers player Tyrone May. In March, police charged May, 22, with recording and sharing sex videos without consent.

In the wake of the incidents, the NRL reportedly lost lucrative sponsorships deals worth “north of $10 million”, announced South Sydney Rabbitohs CEO Blake Solly, and many female followers.

“Rusted-on” Sharks fan Lyn Gannon is the chair of the Cronulla- Sutherland Sharks Member Council and said trying to retain and attract female members within the current environment is a big ask. “It’s difficult to defend being a rugby league fan as a woman, given what’s been going on,” says Gannon, 56. “We’ve got 24 percent women [members]. I’d like to see more women get involved but it’s an uphill battle when you’ve got the players working against you.”

The NRL is tackling the issue on two fronts. In February, with the Australian Rugby League Commission, it unveiled a controversial “no-fault stand down” behavioural policy for players who are charged with serious criminal offences (de Belin, Walker and May have been stood down under the policy). Next, the organisation will conduct a review spearheaded by ARL commissioner Professor Megan Davis, a human rights lawyer who was the rst Indigenous Australian elected to a United Nations body (the NRL declined marie claire’s request to interview Davis).

With my UN hat on, culture is very di cult to change,” she told Sydney’s The Daily Telegraph in March. “What we do know is that the primary and proven way to change culture is through education, but … we need to understand what the problem is.”

The NRL has tried this approach before. In the head-scratching aftermath of Co s Harbour, Sydney academic Catharine Lumby was brought in by then NRL CEO David Gallop to diagnose the problem. Lumby told marie claire she conducted research with 200 players, club CEOs and coaches to gather their thoughts on certain social situations, including scenarios involving women and sex. “You ask questions like, ‘If a women starts a sexual encounter, does she have the right to stop it?’” explains Lumby, who is the NRL’s pro bono gender adviser. “It’s a no-brainer for most men, but some say, ‘No, you can’t do that.’”

Based on such alarming results, Lumby worked with the NRL to design education programs for players. They repeated the research in 2010 and 2018, and it showed, says Lumby, “a 50 per cent improvement in basic attitudes”. She was shocked by the o -season episodes “because this is as bad as it was when I first started working with the NRL”.

Still, it proved a point for Lumby: that the issue may boil down to a case of a few bad eggs. “There are a lot of guys in the NRL who are really good guys,” she says. “But the ones who [are not] are absolute car crashes. And they drag the whole game into disrepute.”

Those rogues might change under better leadership, says former Wests Tigers chair Marina Go. Whenever there was a headline-making incident before the new behavioural policy was ushered in, Go said journalists would come to her for a quote because the male club leaders wouldn’t comment. “The men weren’t stepping up and role-modelling,” says Go, who resigned as chair because she felt she wasn’t being listened to as a senior woman in the game. “If the men were prepared to step up and say, ‘This won’t be tolerated,’ I think behaviours might start to change. But I can’t see it changing any- time soon. It’s very much a boys’ club.”

Roseanne Seymour continues to live in fear in her defunct marriage to a former NRL player. The mother of three, who is a NIDA graduate and was a TV presenter for Channel Nine’s The Music Jungle, recently separated from former Brisbane Broncos and Cronulla Sharks player Brett Seymour after years of alleged domestic violence. “The first time he bashed me it was like I was a footballer on the field,” she recalls. “I was trying to get away and he was body slamming me to the ground. I was unrecognisable. I couldn’t leave the house for a month.”

Roseanne, 37, says she and her estranged husband once shared an idyllic relationship before Seymour, now a league coach, got caught up in the culture of the NRL.

“The players put a lot of pressure on him to go out drinking – ‘Get out with the boys, you’re chained up,’” she recalls. “If he didn’t, he wouldn’t be part of the team bonding.”

Seymour became a heavy drinker (he was sacked by the Sharks in 2009 over an alcohol-fuelled incident) and a problem gambler, who Roseanne says spent most of the couple’s money on bets. Then the beatings began. On December 30 last year, police were called to her Toowoomba, Queensland, home over an alleged domestic violence incident witnessed by a neighbour. Roseanne says her husband crash- tackled her to the ground in her front garden and began choking her before the neighbour intervened.

Seymour has since denied the allegations.

Since first speaking out in April, Roseanne, who now relies on Centrelink payments to support her children, aged six, three and one, says she’s been contacted by multiple women within the NRL community who are suffering domestic abuse. “The game changed my husband forever,” says Roseanne. “I really want to help others, praying they can see the signs early and get out”.

In another disturbing case, Sydney primary school teacher Charlene Saliba last year revealed the abuse she suffered while in a relationship with NRL player Matt Lodge. Lodge, 24, was sacked by the Wests Tigers in 2015 over an alleged rampage in New York City involving allegedly stalking and assaulting two women, and assaulting a man who went to help. “It started with controlling behaviour, then came the emotional abuse,” Saliba, 26, told Sydney’s The Sunday Telegraph. “He started throwing things, physically restraining me, he spat in my face, then pushing and shoving me, which then led to threats on my life.” Lodge, who now plays for the Brisbane Broncos, previously told Fox Sports he had not “hit any women or assaulted any”.

For Taki, depression and severe anxiety set in following her abortion. She and Simona constantly fought and Taki says her partner often threatened her – on one occasion she called police. Feeling scared and vulnerable, she pleaded to the NRL for help. “I told [them] how traumatised I was and [they did] nothing,” she says. “The players are untouchable.” At her lowest point, Taki felt suicidal. “Most days, I’d go home and close the blinds and sit in darkness,” she admits. “I felt alone, pathetic and sad.”

In the end, Simona was deregistered inde – nitely by the NRL in 2017, after Taki made public his gambling issues, including the fact he was laying bets against his own team. He also confessed to drug abuse and stealing from a charity. Simona did not directly address Taki’s accusations but told marie claire he wished her “no ill”. “That ‘Tim’ is in the past and I have moved on,” he said in a statement.

Simona’s manager Sam Ayoub, who took the footballer under his wing following the betting scandal, told marie claire that since 2017 his client had become “a model citizen, dedicating himself to community and charities. He has acknowledged his errors and has built the strength to move forward.”

That includes a hope to return to the NRL. “In 2017 I would have fought that to the death,” said Taki, who broke up with Simona eight months after the abortion. “These days, I have moved on.” It was her daughter Rydah, now eight, who helped Taki turn that corner. “She is the one thing who kept me here, she inspires me to be a better person [and] taught me unconditional love,” Taki says.

The single mum is now a voice for victims of emotional abuse and has raised awareness of abor- tion coercion through public speaking engage- ments. Last year she won

an award for leadership at the Pregnancy Support Awards Dinner at NSW Parliament House. “I realised how much inner strength I have,” she said. “I had an in flux of women saying, ‘I just want to say how brave you are, the same thing happened to me.’”

In light of the NRL’s new behavioural policy and its ongoing review, Taki holds hope for cultural change. “As much as the NRL has hurt me, I want to celebrate any step forward,” she said. “But there’s so much

more that can be done.” Roseanne also feels the code has a long way to go. “My dream was to have my husband, a whole family, but that’s not the way it turned out,” she says. “I blame the NRL and the way they hush things up.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2019 Issue of marie claire.

Following a sordid off- season, the NRL has lost sponsors, fans and respect. As insiders describe a boys’ club culture of bad behaviour, Michael Crooks speaks with the women who have suffered the most, and are now fighting back.

Following a sordid off- season, the NRL has lost sponsors, fans and respect. As insiders describe a boys’ club culture of bad behaviour, Michael Crooks speaks with the women who have suffered the most, and are now fighting back.