The first murder that true-crime fan Kourtney Nichole ever posted about on TikTok was of a woman who drowned her elderly mother in the bathtub, cut up her body into eight pieces, and then hid the parts in various places, including a storage unit and in landfill.

Later, it would be revealed that the woman, Christine Varness, had told her mother, Lois Huysman, she had been sexually abused by one of her stepfathers.

Huysman admitted to knowing about the abuse but blamed her daughter for it, causing Varness to fly into a fit of deadly rage. The crime, which happened nearly 35 years ago, in September 1990, is both terrible and terribly sad. For Nichole, even more so – because the murderer is her grandmother.

“I didn’t find out until I was 12 years old, and when I did, it completely shifted the way I thought about crime in general,” Nichole, 26, tells marie claire. Having grown up watching true crime documentaries and “all things horror” with her family, as well as being very close to her grandmother at the time, Nichole was in shock over the discovery.

“The murder rocked my small home town, and still, to this day, if you mention my grandma’s name there, people know about her. If you knew my grandma but didn’t know her story, you would’ve never been able to guess what she was capable of.”

After killing her mother, Varness told family and friends Huysman had met a wealthy man and moved to Hawaii. But friends were suspicious and informed police. Varness soon confessed, and in 1993 she pleaded guilty to manslaughter. Given her mental state, she served only two years in prison.

Today, Nichole maintains a good relationship with her grandmother, although they are not as close as they once were. Aside from those living in Varness’ small town of Yakima, in the US state of Washington, the crime was largely forgotten — until Nichole made a 15 second TikTok about her family’s deepest, darkest secret.

“One day I came across a video a stranger had posted asking: ‘How many of you know someone who has killed someone else?’ That sparked something in me to talk about my grandma’s case,” she says. “At the time I only had 40 followers on TikTok. Most of those were family and friends, and until that point I hadn’t told a single soul about what my grandma did – not even my childhood best friend. I was trying to hide this skeleton in my family’s closet, so to speak, and I didn’t want to get bullied over my family history.”

The video went viral and Nichole gained 80,000 followers in a day. Talking openly about her grandmother’s case allowed her to harness her love of true crime, and now she has more than 1.5 million followers across her social channels – which focus on murder cases from around the world – and hosts a podcast titled When a Killer Calls. But while Nichole’s experience with murder may be unusual, her fascination with the true crime genre is not.

Statistics show women are the majority of true crime consumers across the globe, double that of men. In Australia, IAB’s 2024 Crime Pays report revealed that true crime is the third-largest podcast category in Australia, averaging more than a million weekly listeners.

Of that, some 65 per cent are women, with 33 per cent aged 25–54. Women are listening to their favourite crime podcast on their work commute, while cleaning the house, or in the car as they wait at school pickup. We’re listening while in our pyjamas in bed, quite literally falling asleep to the sounds of murder.

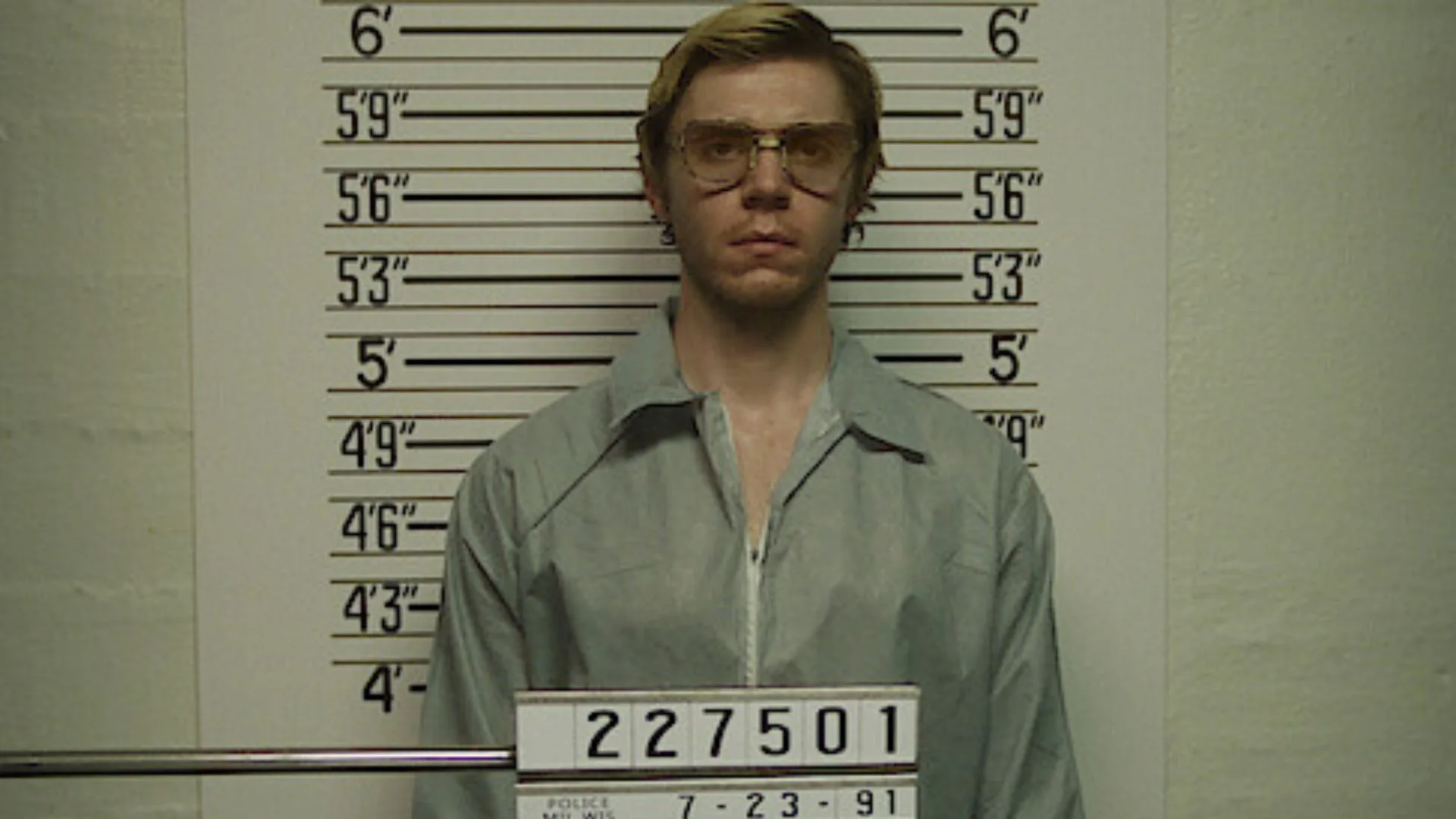

And we’re not just listening, we’re watching too. According to media tracking company Parrot Analytics, true crime documentaries on streaming services grew 63 per cent from 2018 to 2022, and that’s not even counting true crime dramas like The Menendez Brothers, Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, Inventing Anna, Dirty John and the recently released Apple Cider Vinegar, which tells the ‘true-ish’ tale of Australian conwoman Belle Gibson. The New York Times reports that the audience for true crime documentaries and dramas may be 80 per cent female.

It’s clear that women are drawn to the darker aspects of the human psyche. Which raises the question: Ladies, are we OK?

Criminologist and forensic anthropologist Dr Xanthé Mallett certainly thinks so. “It’s totally normal to be interested in true crime because women are fundamentally interested in relationships and understanding them,” she tells marie claire.

“Ultimately, most crime is committed between people who know each other, or at least who interact in some way, even if it’s a stranger murder. So it’s understanding that interaction, and why people do what they do to – and with – each other.”

Mallett says women who watch true crime documentaries most likely also enjoy watching reality TV shows like The Bachelor and Married At First Sight. “We look for red flags in relationships when watching reality television. It’s all about those interplays of relationships. In the same way, sometimes we’ll watch true crime documentaries because we’re trying to look for the red flags, to understand what warning signs to look for, because then if we can see it in other relationships, it increases our likelihood of seeing it in our own or in our friends’ relationships. It gives us a sense of comfort that we may be better at identifying danger.”

Many women are also drawn to true crime as a way to confront their fears in a “safe space”.

“By diving into these stories, they can face their anxieties about violence and victimisation without any real danger,” clinical psychologist Dr Maria-Elena Lukeides says. “True crime can also be a way for women to process their own past experiences or societal fears. Many find comfort in the validation these stories provide, recognising their own concerns about safety in the narratives they hear.”

“They can feel like they’re taking proactive steps to prepare for potential risks. It’s all about finding a sense of empowerment and control over their safety, even if it’s just through storytelling.” Nonetheless, Lukeides cautions against bingeing on true crime non-stop.

“You might find yourself getting more anxious or paranoid, checking your locks a million times or lying awake at night imagining worst-case scenarios. Your brain goes into overdrive, seeing potential danger everywhere,” she says. “It’s important to keep things in perspective.”

Most perpetrators of violent crime are men. Men are mostly victims too, with the World Health Organisation saying 80 per cent of homicide victims are male. However, the victims of intimate partner crime and of serial killers are overwhelmingly women, and it’s these cases that tend to be covered by true crime podcasts and documentaries. So can one be both a true crime fan and a feminist?

“Absolutely,” says Mallett. “Being a feminist is about wanting women to have equal rights, and being interested in true crime isn’t about re-victimising those who have been harmed. In fact, it’s all about centring the victims and the survivors.

“In the past, it’s sometimes been a voyeuristic step through the most salacious stories where we’ve centred the offender, which can normalise violence against women. But we have seen a shift. We’re giving voices to those who don’t have voices anymore.”

Meshel Laurie, the host of popular podcast Australian True Crime, says one of the biggest positives she’s seen from podcasting has been the changing awareness of domestic violence. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, one in four women, or 2.3 million, have experienced physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner since the age of 15.

“Even though the statistics have not improved in Australia, we now have the knowledge that the most dangerous time for a woman to leave an abusive relationship is when she’s leaving an abusive relationship. I don’t think we had any idea of that fact eight or 10 years ago,” Laurie tells marie claire.

“If nothing else, true crime and the repetition of this story and this pattern have taught us as a culture to be aware of that.”

While it may seem as though the true crime genre has exploded only in the past few years, we’ve long had murder on the mind. In the 16th century, pamphlets detailing horrifying murders were published in Britain. Then came along detective fiction and murder mysteries, straddling the lines of true crime. Truman Capote’s 1965 non-fiction novel In Cold Blood is often credited with coining the term “true crime”.

Even though certain violent events such as the 1892 axe murders of Lizzie Borden’s father and stepmother, and the 1994 killing of Nicole Brown and Ron Goldman, in the famed O.J. Simpson case, were sensations at the time, true crime has long been considered a trashy, niche genre, with fans often cast as uneducated stock who swoon over “good-looking” killers and send them love letters in jail. Yes, even murderers have pretty privileges.

That all changed when Serial arrived in 2014. Focusing on the small-town murder of student Hae Min Lee allegedly by ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed, the podcast brought true crime to the mainstream.

The following year, Netflix released Making a Murderer, a documentary exploring the conviction of Steven Avery for the death of Teresa Halbach and his wrongful conviction for the attempted murder of Penny Beerntsen. Both Serial and Making a Murderer captured the zeitgeist of the era, and made an indelible mark on the true crime genre. They also sparked a strong true crime community, which helped propel cold cases back into the spotlight. After Serial, Syed’s conviction was overturned, and though it was later reinstated, he was released in 2022 after almost 24 years in prison.

Closer to home, The Teacher’s Pet brought the 1982 disappearance of Lynette Dawson to Australia’s attention, and Dawson’s husband, Chris, was convicted of her murder in 2022. Recently, Queensland police confirmed that an Australian True Crime listener provided information leading to the arrest of Keith Lees, who was charged with the 1997 murder of his former partner, Meaghan Rose.

Community is a big part of Australia’s number-one true crime podcast, Casefile. What started out as a side project in his living room as host “Casey” – who has remained anonymous since the launch in 2016 – recuperated from surgery has become a true crime behemoth with fans all over the world.

“It’s so good to see that people listen and care and want to help,” he says. “A series that I just did [via off-shoot podcast Casefile Presents] was an investigation into the disappearance of teenager Niamh Maye [in 2002]. A lot of time, a missing persons case will be their height, age, where they’re last seen, what they’re wearing. There’s so much more than that. What I want to continue to do is to work with people to raise awareness, whether it be missing person cases or unsolved cases – using our platform to help people.”

Like most things, there’s a flipside. True crime fans sometimes focus entirely on the crime element and forget the “true”, potentially hindering investigations in their rush to become citizen sleuths and, even worse, ruining lives by pointing fingers at the wrong person. And while the exploitative nature of true crime has lessened, it still exists.

The families of Jeffrey Dahmer’s victims blasted the drama series, saying the show glorified him. One of Ted Bundy’s intended victims said the same thing of the Zac Efron-led film Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile.

In Inventing Anna, conwoman Anna “Delvey” Sorokin is portrayed as a hero – and the real Sorokin went on to star on America’s Dancing With the Stars. Similarly, convicted drug smuggler Schapelle Corby was on Australia’s version of the show.

There’s also the media’s fascination with a certain type of victim: attractive, middle- to upper-class, young, white, female. Coined “missing white woman syndrome”, these victims receive outsized news coverage compared to those who fall outside the parameters. These include murdered and missing First Nations women and children, who in a recent Senate inquiry were found

to be disproportionately impacted by male violence.

The inquiry also found that their stories and lives have been generally ignored by mainstream media.

History shows the true crime genre will continue to evolve. Whatever happens next, true crime fan Nichole hopes we engage with empathy. “The most important thing is that we listen to learn and remember to be kind. Families are victims as well, and they deserve to heal in peace,” she says, likely thinking of her grandmother’s case and its effect on her own family. “Remember, these are real stories, and real people.”

Related articles:

- Best Australian True Crime Podcasts To Binge Right Now

- Beyond 16 Days Of Activism: Why Men Need To Talk About Violence Against Women

- The Untold Story Of Gabby Petito’s Tragic Murder, Explained