In a world where women’s rights are often oppressed, and where the expression of individualism is considered a ‘crime’. Most commonly referred to as Pakistan’s Kim Kardashian, Quandeel Baloch risked her life in order to challenge the status quo.

A beautiful woman in winged eyeliner and a low-cut top lies on a bed urging her favourite cricketer to win the next match. In another post, she pouts at the camera from a hot tub. She posts a selfie with a cleric wearing his hat at a jaunty angle. Her posts are viewed millions of times and the comments beneath them are full of hate. As her notoriety grows, the commentary on national talk shows is just as vitriolic. They call her Pakistan’s Kim Kardashian, and they say she’ll do anything for attention.

Before she became Pakistan’s first social media celebrity, Qandeel Baloch (whose real name is Fouzia Azeem) was a small-town girl from an underprivileged family, raised in the conservative rural province of Punjab. She was married off at age 17 to her cousin Aashiq Hussain and had a son with him, before leaving her husband a year later, saying he was abusive. She was obsessed with TV dramas and dreamt of being a soap star. After moving to Pakistan’s media capital Karachi on her own without her son, she landed a series of minor parts and modeling gigs. When she auditioned for Pakistan Idol – wearing hot-pink tights, sunglasses and sky-high heels – she was mocked by the judges for her high-pitched singing voice. Her audition video has been watched more than 10 million times on YouTube. It was her first video to go viral, but it certainly was not the last.

The videos Qandeel began sharing on social media were a mixed bag – she had a headache, she was bored, she had a song stuck in her head – and for a few seconds every day, thousands watched her coo or feign annoyance or try on a new dress. Her most famous catchphrase was “How em luking” (How am I looking?). The videos were mostly made at night, when Qandeel said she couldn’t sleep. And then they became more risqué – by Pakistan’s standards, at least.

On March 14, 2016, four days before Pakistan played India in the ICC World T20 match, Qandeel uploaded a video to her Facebook page. “If Pakistan wins, I will do a strip dance for the whole nation,” she promised. “And that dance will be dedicated to our captain, Shahid Afridi. Just defeat India once, and whatever you tell me to do, I’ll do it.” A few nights later, she uploaded a trailer for the promised dance. She stood on her bed, wearing nothing but a bright green and yellow bikini and

a white bathrobe stolen from a hotel. The robe was pulled down and tied loosely around her waist. In the video, she cupped her breasts and caressed herself. She swayed her hips like a belly dancer while an Enrique Iglesias song played on her laptop. She drew the robe close to her like a matador’s cape and then flicked it back to reveal a smooth, uncovered leg. The “full film” would be released online if Pakistan wins the match, she promised.

The next day, she wept as she read the comments, “Please shoot her wherever you find her.” “You ugly bitch. People like you should go die … fucking c**t.” “You have no shame, so why are you even wearing this bikini? Take it off, you can earn some more.” “You uneducated bitch … you’re giving Pakistan a bad name. Your pimp family won’t even shoot you. “Your father must be just like you, that’s probably why he doesn’t say anything to you.” “Shame on your parents.”

Qandeel’s trailer went viral. It made the headlines not just in Pakistan, but in India, too. She was called “Pakistan’s hot new internet sensation” and “Pakistan’s very own version of Poonam Pandey.” Poonam, an Indian model and actress, promised to strip for the Indian cricket team during the ICC Cricket World Cup in 2011. Qandeel would go on to repeat what Poonam said at the time, almost verbatim, when asked why she released the trailer – she did it to “buck up” the team. It was a patriotic gesture.

An online campaign to shut down her Facebook page was launched. On March 18, 2016 Farhan Virk, a blogger and self-proclaimed social media activist with more than 100,000 followers on Twitter alone, made a request: “Report [her] Facebook page and share this message. We can’t see a retard like her shaming our nation. Keep sharing this message and reporting her page. We need to get it banned.” Farhan is often accused of operating fake Twitter accounts to spread rumours or impersonate politicians and celebrities. His message about Qandeel was shared more than 3000 times on Facebook.

“We should have drowned in shame the minute we heard her say [she would strip],” Farhan told his social media followers. “In an Islamic state, what kind of thing is that to say?” He accused her of dishonouring the Pakistani flag. “The bikini she is wearing in that video is no ordinary bikini,” he said. “She is wearing the Pakistani flag. Can your honour allow you to stomach that? If you tolerate Qandeel today, then 10 years from now every actress will be doing what she is [doing]. And then we will hang our heads in shame and the people of India will mock us.”

Pakistan lost the match, but the campaign against Qandeel’s social media pages didn’t end. On March 22, 2016, Qandeel’s Facebook account was suspended. She lost an audience of more than 400,000.

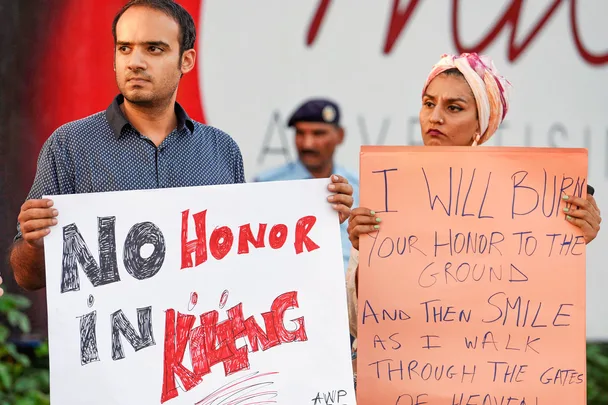

On July 15, 2016, Qandeel was murdered. Her brother Waseem Azeem confessed to the killing, saying her actions had brought dishonour to his family. She was 26 years old. Qandeel’s was not just another honour killing in Pakistan. Her family did not close ranks around the murderer. Instead, in a very unusual move, her father called for her killer, his son, to receive the death penalty. He wept as he praised Qandeel as his pride and called her “my son”. Even in death, Qandeel was exceptional, it seemed.

The day after Qandeel’s murder, an editorial in Pakistan’s English-language newspaper stated the only “crime” she had committed was to “live life on her own terms”, adding, “Women have the right to be themselves, even if they offend conventional sensibilities.” The state, the editorial continued, “must unequivocally demonstrate that [women] do not deserve to be murdered for [doing so]”. The writer criticised the loopholes in existing legislation: “The murderers of women go scot-free … they are forgiven and even supported by regressive patriarchies after killing ‘disobedient’ female family members.”

Five days later, a parliamentary committee approved a bill that sought to close a loophole in existing legislation dealing with honour killings, which allowed killers to walk free.

” The only ‘crime’ Quandeel had committed was to live life on her own terms”

By the time Qandeel was killed, 2016 had already seen an estimated 326 such murders in Pakistan, of which 312 victims were women. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, the most common motive appeared to be retribution or punishment for “illicit relations” (185 murders) and “marriage choice” (99 murders) – the deceased man or woman’s decision to marry someone their family or former partner did not approve of. Of

the 326 murders, 67 were committed by a husband or ex-partner, 64 by siblings, 41 by parents, 30 by other

relatives, 15 by in-laws and 10 by the deceased person’s son or daughter. Many killings took place with the

collusion of family members.

Under the existing legislation, a killer or killers could walk free even after confessing to a murder through the Islamic provisions in the Pakistan Penal Code relating to forgiveness/waiver or compounding, whereby the relatives of the deceased man or woman – in the majority of cases also the relatives of the suspect – could pardon the killer or accept “blood money” as

compensation for the crime.

Two months after Qandeel’s murder, amended laws were unanimously adopted in Pakistan. The most significant change under the Criminal Law Amendment (Offences in the name or pretext of Honour) Act 2016 is that family members can now only prevent a killer from receiving the death penalty. They cannot “forgive” or pardon the killer and enable them to walk free. Everyone convicted of an honour killing will face a mandatory sentence

or life imprisonment.

The response to the amendment was overwhelmingly positive, not just in the local media, but internationally. “Pakistani men who kill their female relatives in the name of honour will no longer be able to evade punishment,” announced The Guardian. The BBC described the new legislation as a “step in the right direction”, while The New York Times noted, “Pakistan toughens laws on rape and honour killings of women.” A senator from the Pakistan Peoples Party told CNN, a “vicious circle has now come to an end” with the new law. It was the kind of positive media coverage that Pakistan rarely enjoys internationally.

In September 2018, Waseem applied for bail after his parents told the court they had forgiven him for Qandeel’s murder. However, his plea was rejected.

Years after she made her last video or uploaded her last photograph, people are still talking about what Qandeel did. She has been written about around the world in publications that include The New York Times, The New Yorker and The Guardian. In a message on Facebook the day before she was killed, Qandeel seemed to reach out to women. “As a women [sic], we must stand up for ourselves,” she wrote. “As a women, we must stand up for each other … As a women, we must stand

up for justice.”

In the last interview before her death, Qandeel spoke for the first time about this kind of feminism. “I don’t know how many girls have felt support through my persona,” she said.

“I’m a girl power. So many girls tell me I’m a girl power, and yes, I am.” These words may have been ignored had Qandeel lived. Today they serve as a rallying point for those who defend her choices.

Qandeel is no longer Pakistan’s Kim Kardashian – if anything, the women who walk in her steps, who aspire to the kind of fame she found, want to be Pakistan’s next Qandeel Baloch.

When Qandeel was buried, her mother covered her hands and feet in henna and kissed them before covering her in a white shroud – a local tradition that shows everyone the woman being buried was a martyr. She died for some cause and died with honour. “When Qandeel’s name is mentioned now, it is not as ‘Qandeel the escort’ or ‘Qandeel the prostitute,’” her friend Jalal says. “It might be ‘Qandeel the victim of honour killing,’ but isn’t that better? I hope that brings her peace.”

On July 24, 2016, Qandeel’s Facebook page was taken down. It went back up a few days later, but many of her posts – such as the trailer for her striptease – had been scrubbed. It doesn’t matter. The videos and her photographs have been copied and shared on multiple social media platforms, blogs and websites too many times to count.

They cannot be erased.

In a world where women’s rights are often oppressed, and where the expression of individualism is considered a ‘crime’. Most commonly referred to as Pakistan’s Kim Kardashian, Quandeel Baloch risked her life in order to challenge the status quo.

In a world where women’s rights are often oppressed, and where the expression of individualism is considered a ‘crime’. Most commonly referred to as Pakistan’s Kim Kardashian, Quandeel Baloch risked her life in order to challenge the status quo.