TRIGGER WARNING: This article discusses domestic violence involving physical, financial and emotional abuse. If you or someone you know is being affected by domestic violence, call 1800 737 732.

Australia has a huge attitude gap around domestic violence. It’s everyone’s responsibility to change those attitudes. Our recent survey revealed that 91 per cent of people agree that violence is a problem in Australia, but only 47 per cent of people believe that violence happens in their suburb. That’s a huge problem.

We can’t rely solely on police showing up on our doorsteps to fix the issue. How women and children experience violence commonly involves a pattern of controlling behaviours over time [unlike other impulsive acts of violence], so the responses, the solutions and the prevention need to take that difference into account.

One of the most useful things anyone can do is believe women and children when they share their experiences. So many women don’t go past the first conversation because they feel shame or that they’re not going to be believed. Yet that first conversation about their experience is the starting point of getting help and changing attitudes.

It’s going to take all of us to see change, and everyone has a role to play. As a friend, it’s your role to have the non-judgemental conversation, or as someone in a service environment coming into contact with children and families, think about how you can use that role to check if people are safe. The relationships and the connections that people have are critical lifelines.

“One of the most useful things anyone can do is believe women and children”

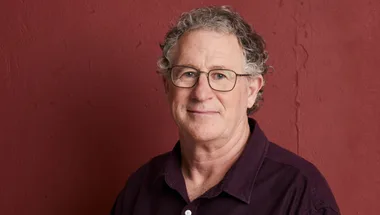

Dr Tessa Boyd-Caine

We also need to hold men accountable, while also holding space for assisting them. The research tells us that many men who use violence are also grappling with their own mental health, substance use, or may have experienced family violence as children themselves. We need to help them grapple with those issues, while also holding them accountable for their behaviour in their relationships.

The services men trust and turn to for help might provide an opportunity to intervene earlier in their use of violence. For instance, some men who have killed their children in the context of family violence had previously interacted with mental health services or drug and alcohol services. These services could provide a touchpoint in that man’s life, to look at whether children and other family members are safe at home.

The adequacy of funding for services is critical, from frontline workers like police and health care to specialist family violence workers. But that’s not where we stop. Currently, our system responses still require victims and survivors to do the hard work, to seek action, to pursue a complaint, to find somewhere else to live if they leave a relationship. We need to improve services and systems to provide better support for victim survivors, we need to know how to work with men who are using violence, and also how to work with boys and young men to make sure they don’t start using violence in the first place.

Read more about Dr Tessa Boyd-Caine and the other inspiring advocates and thought leaders calling for real solutions to Australia’s domestic violence crisis, here.