The 2016 science-fiction drama Arrival, starring Amy Adams as linguistics professor Dr Louise Banks, was a ceiling-shattering moment for female academics. The film, directed by Denis Villeneuve, presented Adams’ character in a race against time to avert a war by finding a way to communicate with extraterrestrial visitors.

Banks’s character was groundbreaking because, for decades, men have been portrayed as brilliant, heroic academics in American and British films. Movies such as A Beautiful Mind, The Imitation Game, The Theory of Everything, Good Will Hunting and Wonder Boys are not only all set at a university or in research institutes – and mostly excellent works of art – but are also all dramas of academic masculinity.

In these movies, women are extras who exist only to offer comfort, help, love, lust and support to the great man until they are assaulted, dumped or divorced.

Women make up 49.3% of academia in America, 45.7% in Britain and 45.6% in Australia. Yet female academics have barely appeared as rounded characters in movies.

I still remember my joy and shock at watching Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, five years ago, in which Sandra Bullock plays Dr Ryan Stone, a medical engineer who is stranded in space after the mid-orbit destruction of her space shuttle. Here was a blockbuster movie starring a complex, female academic character. Yet Gravity was not the breakthrough for which I had hoped. A single momentous work cannot, by itself, change things.

The absence of these characters in mainstream film matters, because most women in academia must still fight to tell their own stories and fight against the stories that distort or erase them. And on the rare occasions when women have appeared as academics in Hollywood films, their depictions have often been awful.

The most notorious examples are characters such as the naive palaeontologist Dr Sarah Harding (Julianne Moore) in The Lost World: Jurassic Park, or worse, the talented PhD student Hannah Green (Katie Holmes) in Wonder Boys, who lusts after her male supervisor.

While Dr Harding is ostensibly an intelligent academic, in The Lost World she more accurately serves as a damsel-in-distress. Ironically, it is Dr Harding’s supposed intelligence that puts her in distress in the first place. (Bring the baby Tyrannosaurus rex aboard the mobile home? Sure mommy, the nine-ton predator will never smell a baby or hear its cries in there!) When Dr Harding’s scientific shortsightedness leads to trouble, she proves she can wail on par with any princess in jeopardy.

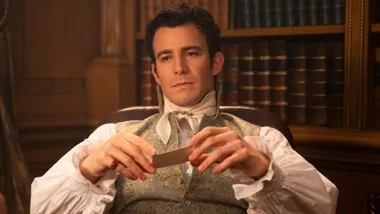

The Wonder Boys’ Hannah Green is the ideal student for hyper-masculine academics. She is beautiful, brilliant, and innocent. She lives for her studies. And she has a crush on her male professor. Moon-eyed, she gushes:

I was thinking it’s like all your sentences seem as if they’ve always existed, waiting around up there, in Style Heaven, or wherever, for you to fetch them down.

In short, she is the perfect muse.

Women wince at these unrealistic portrayals. They hurt because many viewers will take these stereotyped depictions and transfer them to any female academic they later encounter.

The brilliant women who deserve movies

One solution to all this is to change how and what stories are told. So here are my picks of women with brilliant minds who deserve blockbuster movies of their own.

Hypatia, the Egyptian astronomer who built an astrolabe, the first instrument for calculating the position of the sun, moon, and stars at any given time. She taught astronomy and philosophy in ancient Alexandria and her classes where always popular. Students and other scholars would crowd in to hear her explain that you must reserve your right to think – for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all.

Maria Reiche, the 20th century German archaeologist who found that hundreds of mysterious lines etched into the dry Peruvian desert, called Nazca Lines, actually correspond to the constellations in the night sky. She flew helicopters and planes to map the lines and used so many brooms to clean them that some people thought she was a witch.

Ada Lovelace, the British mathematician who in 1843 wrote the first computer program in history, way before modern computers were invented!

Grace Hopper, the American computer scientist. Thanks to the programs she wrote for the first computer, called Mark I, US forces were able to determine how to detonate atomic bombs.

Marie Curie, the scientist who found out that some minerals are radioactive, give off powerful rays and glow in the dark. Born in Poland in 1867, she moved to France to study. She discovered two new radioactive elements – polonium and radium – and won two Nobel prizes for her work. She died in France in 1934 due to exposure to radiation.

Jane Goodall, the British primatologist who has discovered that chimpanzees have rituals and use tools, that their language comprises at least 20 different sounds, and that they are omnivores.

Maria Montessori, an Italian physician and educator who lived from 1870 to 1952. Instead of applying old teaching methods, she watched children to see how they learnt. Her innovative teaching method is applied in thousands of schools and it helps children all over the world grow independent and self-sufficient.

Mae C. Jemison, the first African-American woman in space. She graduated in African-American studies, chemical engineering, and medicine and learnt to speak Japanese, Russian, and Swahili. After becoming a doctor and volunteering in Cambodia and Sierra Leone, she then applied to NASA to become an astronaut. Dr Jemison was selected and sent into space on board the space shuttle. She carried out tests on other members of the crew. Since she was not only an astronaut but also a doctor, her mission was to conduct experiments on weightlessness and motion sickness. When Dr Jemison came back to Earth, she realised that her true passion was improving health in Africa. So, she quit NASA and now runs a company that uses satellites to do just that.

Signs of progress

Filmmakers continue to produce movies with male actors (The Martian), with academic characters played by male actors (Doctor Strange) and with research institutes led by men (Interstellar).

Nevertheless, the developments since Arrival are encouraging. 2017 saw Hidden Figures, the movie about the three brilliant African-American women at NASA – Katherine Johnson (Taraji P. Henson), Mary Jackson (Janelle Monáe), and Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer) – who served as the brains behind one of the greatest operations in history: the launch of astronaut John Glenn (Glen Powell) into orbit. It was a stunning achievement that restored the US’s confidence, turned around the Space Race, and galvanised the world.

And this year, Annihilation was launched. Based on Jeff VanderMeer’s bestselling Southern Reach Trilogy, the movie stars Natalie Portman (as a cellular biologist), Jennifer Jason Leigh (as a psychologist), Tuva Novotny (as an anthropologist), Tessa Thompson (as a physicist), and Gina Rodriguez (as a paramedic). If Gravity chipped the ceiling for female academics; Arrival appears to have finally smashed it.

If Arrival does succeed in transforming how filmmakers perceive and represent women and female academics, it is due not only to this one movie being good and profitable, but also to the long, slow work by female and male actors, agents, directors, producers, researchers, writers and others that has gone before it. For decades, people have been researching gender representation in media and advocating for equal representation of women.

Still, Arrival should really have been just a science-fiction drama about a linguistics professor, who happens to be female, leading an elite team of investigators. Yet, with so few movies about female professors, or female humanities scholars, or female lead investigators, or female academics in general, it became highly symbolic.

The real test of how far things have progressed will be when a female academic has the luxury of being the star of a bad movie. That is one measure of equality — the right to be bad and not suffer for it, rather than the demand, placed on female academics and actresses, to be exceptional just to be seen.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.