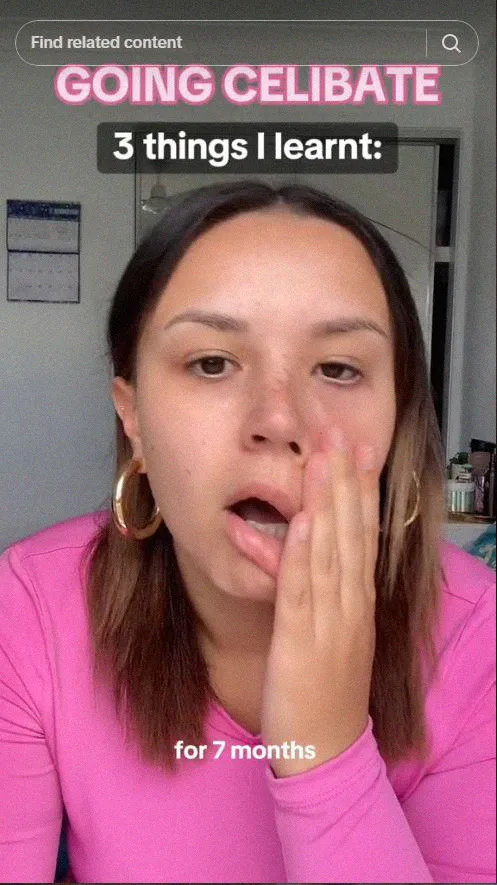

When Chloe Scull told friends at the beginning of last year she was quitting sex, they thought she was joking. But the 25-year-old couldn’t have been more serious. Dating and casual sex had led to low self-confidence, making the Queenslander question whether there was something intrinsically wrong with her.

“For so long I felt men characterised me as the type of woman they wanted to sleep with but not be with,” she says. “I was never taken seriously, and that really hurts. Especially being surrounded by so many friends in healthy relationships with amazing partners who would move mountains for them. I didn’t understand why I couldn’t find the same.”

So Scull decided to take a break. Her sexual sabbatical ended up lasting seven months and was so transformative that the content creator, who goes by @chlo_muny on TikTok, decided to share her experience to help others who may be curious about abstaining from sex.

“Celibacy allowed me to take my power back and switch the narrative. It gave me the time and space to truly heal and learn to find happiness in other aspects of life, instead of focusing my energy on romantic connections,” she explains. “It forces you to find fulfilment as a single person. And you have higher standards in dating – now that I know I can survive and thrive on my own, why would I accept anything less than amazing?”

Scull is part of a growing movement of mostly Gen-Z women who are making the choice to become celibate for a period of time. They’re called “volcels”, after voluntary celibacy. The inverse of that is the much-maligned “incel”, which stands for involuntary celibacy, a term used to describe men who consider themselves unable to attract women sexually, often leading to hostile and extreme beliefs.

Voluntary celibacy rose to particular prominence on TikTok during the pandemic years, where the celibacy hashtag racked up millions upon millions of views. The hashtag currently has an astounding 263 million views and counting.

“The lockdown period prompted a significant re-evaluation of sex and relationships for many people,” Chantelle Otten, sexologist and director of The Australian Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine, explains to marie claire. “The enforced solitude and break from regular social interactions provided a unique opportunity for introspection and led some to choose celibacy, focusing on self-growth and healing. The pandemic’s impact on how we view and engage in intimate relationships is profound and ongoing.”

But the rise in celibacy is far from just a TikTok trend. A 2022 survey by dating app Bumble reported 34 per cent of respondents were not having sex. In 2019, ABC’s national survey Australia Talks found that 40 per cent of people 18 to 24 “never” have sex. So, even before the pandemic hit, sexual abstinence was growing.

Moreover, a look at the latest Census figures from 2021 showed fewer marriages, and more Australians living alone than ever before: one in four households are now only one person. These statistics are replicated in both the UK and US. Britain’s National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, which tracked sexual behaviour in certain years (1991, 2001 and 2012), reported that fewer than half of men and women aged 16 to 44 have sex at least once a week.

A 2021 survey from the University of California, Los Angeles, found that Americans aged 18 to 30 who had no sexual partners in the year prior reached a decade high of 38 per cent.

Nevertheless, associate professor Lauren Rosewarne of the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne warns against overemphasising the rise of celibacy. “The number of people who deem ‘not having sex’ as central to their identity is relatively small so this trend shouldn’t be overstated,” she says. “Realistically, most people will have ‘dry spells’ but won’t consider themselves celibate. That said, statistics do show that people in many countries, particularly younger people, are having less sex. This doesn’t mean these people consider themselves celibate, have made a conscious choice to be celibate, or plan to stay in this state permanently.”

Society is also now at a point where intercourse is no longer seen as the only acceptable way to achieve sexual pleasure. Self-love in the form of vibrators and other sex toys, gaming and AI, pornography and Only Fans has been readily embraced by young people seeking a more celibate life. And for those in relationships but abstaining from intercourse, mutual masturbation is sometimes seen as an acceptable way to be intimate while still maintaining a form of celibacy.

For Catherine Gray, bestselling author of The Unexpected Joy of Being Single, celibacy was one of the best decisions she ever made. In 2014, long before celibacy was a hashtag on TikTok – indeed, before TikTok was even invented – the writer stopped having sex and took a year off dating. Gray was 34 years old, the age where she was, according to family and wider society, supposed to be “intensifying the hunt for a husband”.

“I don’t think the celibate revolution is about sex. I think it’s about a global realisation that we’re not half-people, incomplete or unrealised as women when single,” she tells marie claire. “In many ways, we can only become fully complete when we take the time – even if only a year – to stand by ourselves. We find out who exactly we are, what we want, what we enjoy. It’s almost impossible to do that when somebody else is in the picture.”

Celibacy is not a new concept, of course. Many major religions like Catholicism, Hinduism and Buddhism have featured celibacy for hundreds of years, whereby its clergymen and women take a vow of chastity. Premarital sex is still considered a sin in many religions and cultures, although the sexual revolution of the 1960s has had a far-reaching impact on the “rules” of sex – from a Western perspective, at least. Celibacy for religious reasons is still a driving force today, with high-profile couples like Justin and Hailey Bieber, Miranda Kerr and Evan Spiegel, and Mariah Carey and (now ex-husband) Nick Cannon saying they abstained from sex with each other before marriage. And who can forget the Jonas Brothers and those infamous purity rings?

Religion aside, there are a litany of motivations for becoming celibate. Voluntary celibacy is a personal choice and many people choose not to disclose their reasoning, even privately. Some might abstain from sex to heal from traumatic relationships, including revenge porn, sexual abuse and domestic violence. Professor of Sociology at Monash University Jo Lindsay says it’s possible that heterosexual relationships are no longer seen as easy or safe for many women.

“Sexual assault rates are high and domestic-violence rates continue to be high – many women may have been hurt in relationships or seen friends and family hurt,” she explains. “There is also enhanced media attention of these issues, including the #MeToo movement. This may also have an impact on celibacy rates.”

A 2020 study by the Women’s Health Research Program at Monash University found 50 per cent of women aged 18 to 39 experienced sexually-related personal distress, meaning they felt guilty, embarrassed, stressed or unhappy about their sex lives. Of these, 20 per cent had at least one sexual dysfunction, the most common being low sexual self-image. Sex therapist Pamela Supple says many people are overwhelmed and burnt out by all the noise and pressure of dating and sex.

“When dating apps first came out, people were going on 30 dates every two weeks or something, which is fine. They were having sex, but it was leaving them empty. People being ghosted. People being judged on what they look like at the flick of a hand – that in itself is exhausting,” she tells marie claire. “People are now looking for and finding solace within themselves. They’re abstaining from sex to keep a bit of a clear head.”

Otten believes the rise of celibacy shows a rejection of hook-up culture and reflects a shift in the priorities and values of young people. “Many are now focusing on personal growth, mental health and professional aspirations, finding these more fulfilling than the fleeting nature of hook-up culture,” the sexologist explains. “Social media and dating apps have played a dual role in this trend. On one hand, they’ve exposed the often superficial and unsatisfying nature of casual sexual encounters.

On the other hand, they’ve created platforms for sharing and normalising the choice of celibacy, as seen with the popularity of the celibacy hashtag. This collective online narrative helps young individuals feel supported and understood in their decision to embrace celibacy, fostering a sense of community and validation.”

That is certainly the case for 29-year-old Jordan Jeppe. In 2017, Jeppe embarked on her celibacy journey and remained steadfast for five months. After breaking her sexual abstinence for a one-night stand, she returned to celibacy for another eight months. Now in a three-year relationship, Jeppe works as a celibacy coach and has nurtured an online community where people can learn to navigate their own path of celibacy or seek personalised guidance.

“The beginning of celibacy was an act of desperation,” Jeppe tells marie claire. “After continuously losing myself in relationships and experiencing heartbreak after a three-month fling, removing myself from partners felt like a lifeline to finding myself again.”

Jeppe credits her decision to quit sex with helping her find her “first ever” healthy relationship. “By consciously embracing celibacy prior to entering into my current relationship, I established a solid foundation for a partnership built on genuine emotional intimacy and shared values,” she says. “This intentional choice paved the way for a deeper understanding of my own desires and boundaries.”

Supporters of celibacy cite many benefits: as well as improved mental and emotional health, having higher dating standards and finding fulfilment as a single person, celibacy’s advantages include a reduced risk of STIs and pregnancy, and an increased focus on other areas of life.

“The most surprising benefit was how supremely relaxing it was, removing ‘find husband’ and ‘be sexy’ from my to-do list,” writer Gray says. “My phone no longer had the power to lift me up or smite me down, thus my screen time halved. I had heaps more time for writing, yoga and interior decorating, now that I’d quit my second job of dating apps.”

But there can also be some downsides to celibacy: loneliness, sexual frustration and judgement from others. And then there’s the big one no-one really talks about, Jeppe says: “The internal struggle of ‘fear of missing out’ or FOMO from the commitment to celibacy raises the question of potentially bypassing the chance to encounter the partner of one’s dreams.”

To this, Gray has an unwavering response. “Ignore the tyranny of ‘what if you miss out on someone great’,” she says. “Here’s what I say to those people: ‘I don’t want to miss out on someone great, that’s true. But that includes myself.’”