Trigger Warning: this article mentions mental health and suicide and may be distressing to some readers.

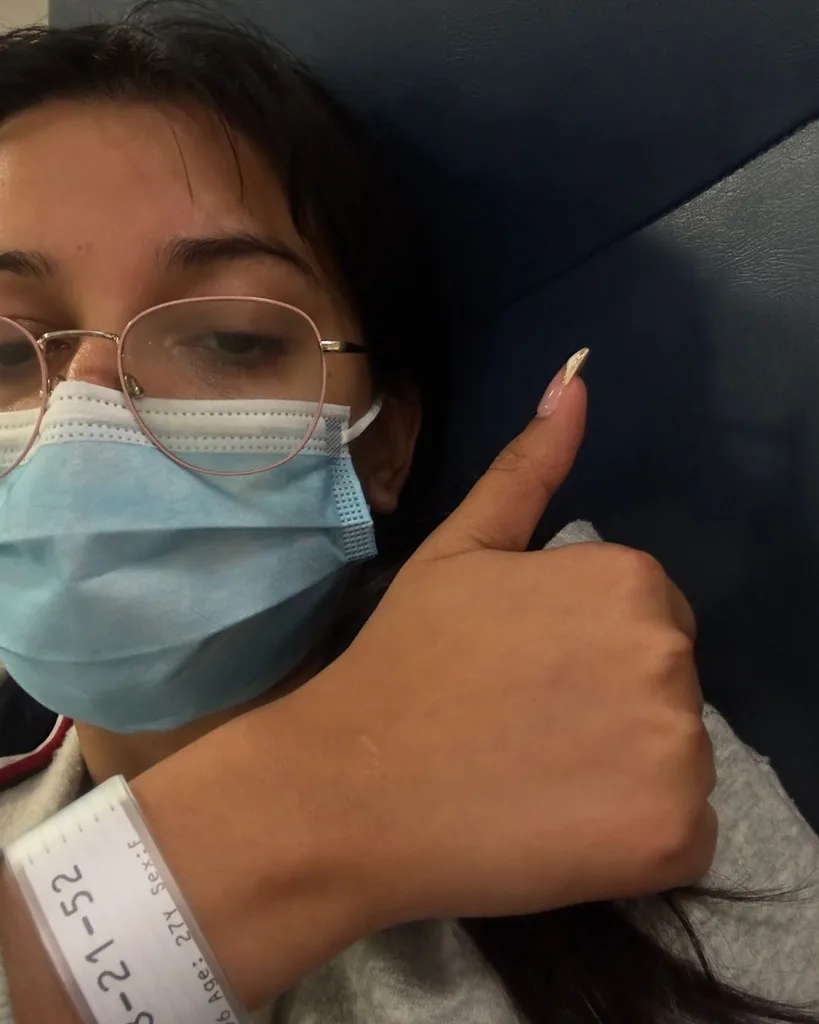

I know the hum of harsh fluorescent emergency room lights too well. I’ve seen and heard them more times than I can count, first when I was 14, and then most recently, last year at 27. I’ve probably been sent to the hospital for a mental health crisis upwards of ten times, and in almost every instance, instead of being admitted to a psychiatric unit, I was kept in emergency overnight, left with a promise of a visit from the mental health team that never arrived. A pain all too familiar for those who seek support.

So I had to be the one to find my own. Over the course of fifteen years, I’ve worked with therapists, trialled treatments, and spent more than the equivalent of a house deposit on care because our system can’t provide the long-term support I needed.

I’m one of countless Australians who’ve slipped through the cracks. So when the 2025 federal budget’s mental health announcements dropped, I hoped for bold action to ensure no one else endures what I did. Unfortunately that is not the reality.

Youth mental health is in crisis. Prevalence has surged by 50% in the last decade. Almost two in five young Australians have experienced a mental health issue. The 2025–26 budget was a chance to finally bridge that gap; instead it offered only one small-scale measure. The additional funding of $46 million over four years from 2024–25 to continue digital mental health services.

When analysing funding around mental health further, you can find that last year’s budget made headlines with a supposedly “big” mental health package of $888 million. In truth, that figure is spread over eight years and largely tied to the aforementioned digital mental health services which still are yet to open their (virtual) doors.

This new online platform, expected to arrive in 2026, is slated to offer up to 10 free sessions for “low-intensity” needs, a welcome idea, but cold comfort to those in crisis today. Unfortunately, a suicidal teenager can’t wait until 2026 for help to materialise. We don’t force people to ration physical health care, why is mental health any different?

And if the budget’s mental health measures are underwhelming overall, they are especially meagre for communities that face the greatest barriers. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples endure disproportionate mental health challenges, yet previous budgets offered token support, just $10 million in targeted Indigenous mental health funding last year, a figure widely criticised as inadequate.

This year, the government finally increased its commitment: $24.7 million over four years will go toward First Nations social and emotional wellbeing and mental health initiatives. This includes establishing culturally appropriate, place-based trauma supports and developing First Nations-led mental health assessment tools, as well as scholarships for up to 150 Indigenous psychology students to grow a culturally safe workforce. These investments are welcome and needed. As the RANZCP noted, building a pipeline of First Nations psychologists is vital to improving access in Indigenous communities.

However, $24.7 million spread nationwide and across four years is still far too small given the scale of need and the historic under-resourcing of Indigenous mental health services. First Nations Australians remain in urgent need of a larger, sustained commitment.

Other communities received even less funding. Take LGBTIQA+ Australians, who experience significantly higher rates of depression, anxiety and suicide risk due to stigma and discrimination.

The budget’s offering here was essentially status quo: it continues funding for QLife, the national queer peer support hotline, with $0.4 million for 2025–26 to keep this lifeline operating.

That funding “literally saves lives,” as Nicky Bath of LGBTIQ+ Health Australia noted, but it’s a continuation of an existing service, not an expansion. Broader LGBTIQA+ mental health initiatives, such as addressing the glaring gaps in services for trans and gender-diverse people remain as unfunded wish-lists.

For culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, the story is similar.

These communities often struggle with a lack of accessible, culturally appropriate mental health care, and language barriers that make it harder to get help. Yet the 2025–26 Budget contained no specific new funding to improve mental health support for CALD Australians. A national program called Embrace Multicultural Mental Health exists to provide a focus on CALD mental health, but no significant boost or expansion for it was announced.

Perhaps the most glaring omission in the budget is any serious effort to build the mental health workforce we desperately need. It doesn’t matter how much we talk about awareness or ask people to reach out for help if, when they do, there’s no one there to provide care. Right now, that’s the grim reality for too many.

Psychiatrists, the medical specialists who handle the most complex mental illnesses, are in critically short supply. Long waitlists and even the closure of some private psychiatric hospitals are symptoms of a system stretched beyond capacity.

The RANZCP warned that “Australians with serious mental health care needs are once again being left behind, with this year’s budget failing to deliver any meaningful investment in the specialist workforce needed to support them.”

The government’s focus on “low-intensity” online services might reduce mild cases in the long term, but it does nothing for someone acutely suicidal tonight.

The most painful gap, the one I fell through, is long-term care for chronic, complex mental illness. Policymakers love pilot programs and digital rollouts. But for those like me, who have cycled in and out of emergency without ever receiving substantial support, we need sustained, person-centred care.

The budget’s focus on moderate-level services is welcome, but there’s still no plan to restore extended Medicare rebates or fund evidence-based treatments like DBT in the public system. I spent $20,000 on my DBT program. It changed my life. But it shouldn’t take that kind of money and privilege to access care that works.

Investing in follow-up care, ongoing therapy, and peer support isn’t a luxury, it’s a lifesaver. Yes, there’s a plan for ten free sessions through a new national counselling service by 2026. But what about those of us who need 100 sessions over a few years? Group therapy? A multidisciplinary team? We cannot pretend that a one-size-fits-all platform can reach someone dealing with complex trauma or severe PTSD.

I’m not writing this as a laundry list of budget failures. I know reform takes time. But I’m asking for an investment that reflects the scale of suffering in our communities. Each of the gaps I’ve outlined isn’t just a policy issue; it’s a life or death issue for Australians out there, right now.

Australia can, and must, do better. We have the experts, the advocates, and public support. What we need now is political bravery. That means scaling up investment, funding long-term care and not just flashy pilot programs. It means measuring success not by how many programs were announced but by how many lives are saved and transformed.

As a survivor who almost became a statistic, I am grateful to be here to write these words. I carry hope that things can change, because I’ve seen how the right support at the right time does save lives. That hope is what keeps me fighting for better policies and working with groups and foundations such as ALLKND, even when I’m tired and disillusioned.

It’s what leads me to share my story like this, reliving painful moments, in the faith that someone out there with the power to help will read it and feel moved to do more. Each measure we fund, or fail to fund, can tip the scales between life and death for someone.

If you or someone you know needs help you can call Lifeline on 131 114 or Beyondblue 1300 224 636.