I am lying on a stretcher. My hair is wet and curly, the dark brown locks contrasting with the bright red of my bikini. My denim skirt is soaked through with water and has been painstakingly unbuttoned by the boy on his knees before me. His well-toned muscles ripple in the light, accentuated by the oil on his chest and shoulders.

As I look into his eyes and place his hand on my hip, the scent of the oil cloys in the air between us. I try not to break character as I remember our joke that we smell like Betty Crocker cake mix—I’ll never be able to smell a baking cake without being brought back into this memory. The humour grounds me in a moment that feels surreal. The moment in which I become the first person with a disability in Australia to be in a sex scene on television.

PJ and I move through the choreography that we mapped out earlier with our intimacy coordinator. He lies on top of me, our dark hair tangling together as instructions are called to us from behind the camera: where to put our hands, how to move our heads, even what sounds to make.

You’re probably wondering how I got here—and, truth be told, so am I.

I’d always been drawn to acting, so much so that I wanted to study Drama in my final year. Unfortunately, I was the only one who did so that meant there were definitely not enough numbers for a class. I saw performance as an extension of my love of storytelling, but my ambition also came from my desire to defy the preconceived notions of what disabled kids are capable of. Even so, never in my wildest dreams did I think it would land me here, starring in a prime-time show on SBS Television.

Despite growing up as a devotee of the Disney Channel, aching to have the limo out front, I have always been aware of the barriers between me and the stage. But performing was the one place where I felt as if I could control how people reacted to me—where I could use the quirks of my body and its limits to tell a story in a unique way. On stage, I could almost forget all the parties I was never invited to, all the boys who asked me out as a cruel joke, all the times I ate lunch alone, just wishing for people to see the vivid personality I had inside, instead of thinking of me as the ghostly girl who deserved nothing but mockery and derision.

Like a lot of other drama kids, I got swept up in the fantasy of what it would be like to be a real actor, to escape my own reality and slip into someone else’s. There was one small caveat, however: my disability, cerebral palsy (or CP for short). Unfortunately, no matter how hard I tried, I continued to feel as if I was locked into one role, one narrative. And it was a role without dimensions, nuance or a story arc. The punchline.

When I looked for actors like me on stage or screen— for a role model who could show me that my dreams were possible—all I saw were able-bodied actors winning awards and praise for inhabiting bodies like mine. But, of course, they could cast these personas off and walk away as soon as the director called, ‘Cut!’ Not once had I seen a disabled actor on screen. We were invisible, excluded from telling stories about our own experiences.

It was then that I realised that our world does not make space for those of us who navigate it in a wheelchair. And so that dream faded, and I left acting where it belonged: inside the walls of my high-school drama room, written off as ‘just a phase’. Until I received an email that changed my life.

The email was from a producer, Liam, who explained that he was working with SBS on a groundbreaking comedy/drama series initially called Let Me Help but later known to all of you as Latecomers. It followed the lives of two leads, Sarah and Frank, as they navigate the turbulent waters of love and sex as young adults with cerebral palsy. Two of the show’s three creators, Emma Myers and Angus Thompson, also had CP, and Liam made it clear that Sarah and Frank would be played by disabled actors.

I was floored. A show where disabled voices called the shots? Where our stories were told not in a way that was tinged with pity, but with the gritty light and shade of our real lives? A TV series born of lived experiences, and which saw these characters as full people with rich inner lives, expressing the same needs, desires, dreams and struggles as everyone else? Finally. I’d only been waiting my entire life.

The production team wanted to know whether I’d be interested in taking part in what they called a ‘read-through’, which was a workshop designed so that Angus, Emma and their acclaimed counterpart, the hilarious Nina Oyama, could hear the lines they’d spent months slaving over spoken by real people. The read-through would show the writers which scenes and dialogue were working and which weren’t. All the actors would be given space to share their thoughts and notes on the script, but the invitation did not mean we would necessarily be involved when filming started.

My heart stuttered in my chest as I read the scripts Liam had sent over. Were they kidding? Of course, I wanted to be a part of this! The chance to play Sarah, even for a couple of hours, felt incredibly special. I could already see the moment, months away, when I’d be sitting down to watch the show with my family and friends, marvelling at whoever the lead actress was. How much she was killing it. How important it was for her to carry this story for our community, a story that, even in this raw form, I could quickly see would revolutionise the way disabled stories were told. The idea that I might play Sarah wasn’t in my mind at all as I turned up to a PCYC and took my place with the other actors.

I was packing up my things, getting ready to meet Mum outside, when a shadow fell across the white desk in front of me. I looked up, coming face to face with the piercing blue eyes of director Madeleine Gottlieb and the kind yet sharp gaze of the head of casting, Danny Long. Figuring they just wanted to introduce themselves or thank me for coming, I remained calm and smiled. Then Danny opened her mouth and, in a no-nonsense tone that left no room for argument, said, ‘You’re auditioning for the show.’

I froze, waiting for them to start laughing. This had to be a joke, right? When no laughter came, I snuck a look at Mads, whose face was earnest. She nodded ever so slightly, as though she knew I needed a small push, some reassurance that I could really do this.

‘What? Why would I do that?’ I heard myself ask in a voice that sounded shaky and confused.

Danny smiled as she said gently, ‘Because you can act.’ I stared at her. ‘I can?’

She nodded, and something inside me laughed. The little girl who’d always wanted to try working in front of a camera then gave me a playful shove, and suddenly I was saying, ‘Okay! What do you need me to do?’

I would have to put together an audition tape, they explained. ‘Okay, cool . . . Just one question: how do I do that exactly?’

Once I’d worked things out, I enlisted Mum to help me run through my lines. We tried not to break into hysterics as we made our way through the awkward scene where Frank and Sarah are stuck together while they listen to their carers hook up. After six or seven takes, we emailed the best take we had. I couldn’t help but laugh at my own audacity. There was no way they were going to pick me. My only acting experience had been in a high-school classroom—there were so many other talented actresses out there who actually knew what they were doing. But I was damned proud of myself for auditioning anyway. To my shock, I made it through several round of auditions, even as the little voice in my mind cut me down to size: I wasn’t even supposed to get a callback . . . They aren’t going to pick me. By the time I’d made it to the final two, the voice

was saying: Oh shit! What if they pick me?

The night before my final audition—a chemistry test with Patrick Jhanur, who was playing Elliot, Frank’s carer—I tried to pull out. I was spooked by how my own personal experience, or lack thereof, mirrored Sarah’s. What if I struggled to draw the line between fiction and reality?

How, for example, would I be able to hold it together while Sarah was called ‘unfuckable’, when those harsh words echoed some of my most vicious insecurities? What would it do to my sense of self to experience my first kiss in an environment where the feelings behind it weren’t real? How on Earth would I navigate the sex scene, plagued as I was by both the feeling of failure that I hadn’t experienced it yet and intense body- image issues?

In the end, two things happened: As I called Mads to pull out, having not yet done the chemistry test with PJ, she said she understood but that it was a shame because the production team were pretty sure that I was the actor they wanted to play Sarah, triggering my epic FOMO—how would I watch the show knowing it could have been me, if only I’d been brave enough?—and I reminded myself that I’d spent my whole life so far searching for a face like mine and a story where I could feel seen. Now I had the chance to be what I and the rest of my community were looking for—that face I’d been so desperate to find. It was the one in the mirror. I knew I’d never be able to live with myself if I passed up this opportunity, so I took a deep breath and jumped straight in.

From the minute PJ and I met over Zoom we just clicked. It was as if we’d known each other forever, connecting in such a strong way that the scene we did (that tender moment between Sarah and Elliot in the car after the worst first date of all time) made Mads and Danny cry. With that reaction, PJ and I felt pretty confident we had the roles—a hunch that would be confirmed a few weeks later when official offers came through for both of us.

I had no idea what to expect the first time I stepped onto set, and my mouth hung open when I saw the sheer number of people it would take to make our show. I was absolutely terrified. My hands shook through every one of the ten takes I needed to nail my first scene, impostor syndrome whispering in my ear the whole way through. You’re not really an actor . . . Whenever I caught a glimpse of the monitor or listened to the way the crew reacted, I felt like I was having an out-of-body experience. That’s not really you . . . Except it was. It is. I’m the girl on the poster.

The two and a half weeks I spent on set were some of the most intense weeks of my life, but they were also some of the best. We worked eleven-hour days, often longer, shivering through take after take as the Sydney winter set its claws into our summery wardrobe. We filmed on beaches and boardwalks, in adult stores and strangers’ houses. It was bizarre seeing my framed childhood photos in a kitchen I’d never been in before. One of the funniest scenes was Sarah’s disastrous date with Frank. I had to try really hard not to laugh as the art department threw ‘vomit’ concocted from custard, biscuits and blue Powerade at my face. I was lucky enough not to cop it in the mouth, but the smell alone sent my own stomach rolling with nausea. The crew cheered when it landed in my hair or hit me in the forehead.

When Mads calls, ‘Cut!’ on the final take of the sex scene and tells PJ and me that they have all they need, she brings the monitor to us. We sit huddled on the stretcher in the lifeguard’s office, watching the magic captured by the camera. It doesn’t take long before we all start to cry, hit by the weight of making television history.

It doesn’t matter that, just moments earlier, PJ and I had been freezing, the camera only inches from my head as I lay topless, my heart beating out of my chest. What matters is that we have created a scene that feels real and intimate, a scene between two people whose feelings had spilled over into something that was both awkward and beautiful all at once. What matters is that we are going to show disabled people everywhere that we can be loved and desired. That we deserve to feel sexy.

What I found on the set of Latecomers is almost indescribable. So is what the story gave me. I’ve found people to fill the empty lunch tables of my past. People who don’t stare at me like I have two heads when I tell them about the things I want to make and the stories I want to tell, but who instead say, ‘How can we help?’ I’ve found people who saw me, all of me, and didn’t look away. Not even at the scary bits. People who have changed my life so much that they’re stuck with me now, because I’m not willing to imagine them being anywhere else.

I’ve found a whole new world. A world of actors and screen- writers, producers and directors. And I’ve realised that, aside from the obvious, there are absolutely no limits to what I can be and what I can achieve. That the doors may be closed, but they’re not locked. All I have to do is swing them open and let myself in.

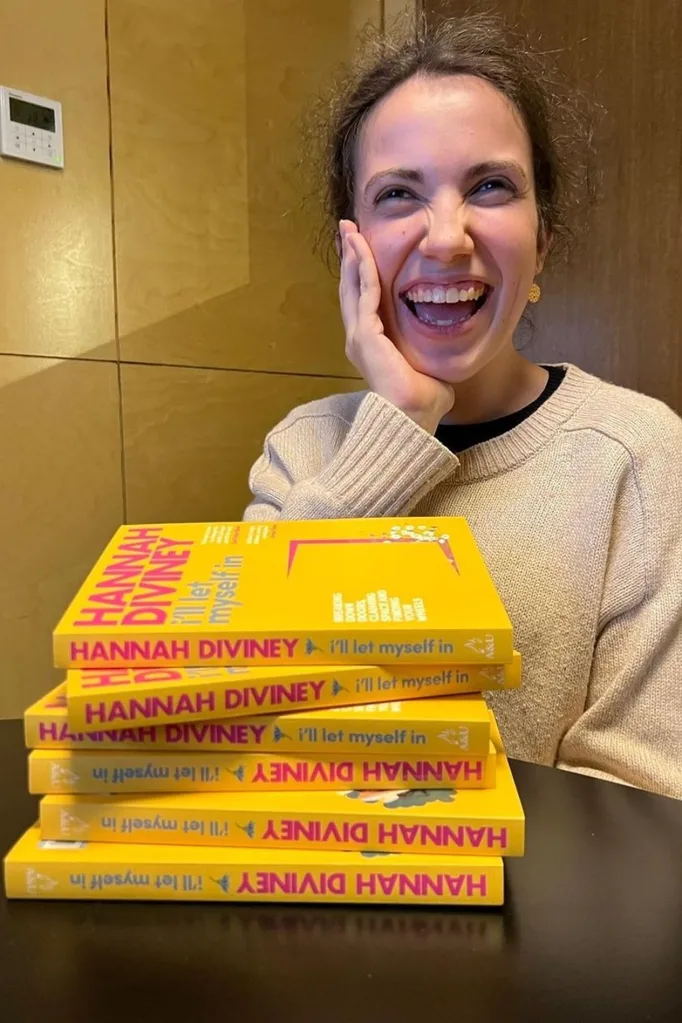

This is an extract from Hannah Diviney’s new book I’ll Let Myself In, available at book shops near you, Booktopia, as well as on Amazon Audiobooks.

Hannah Diviney is a leading writer, disability and women’s rights advocate in Sydney, Australia. She began her career at Mamamia at the age of fifteen and since then has become the co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Missing Perspectives, is the face of the global campaign for a Disabled Disney Princess and is the woman who called out Lizzo for using an ableist slur. She also plays the female lead in the SBS TV Series Latecomers. I’ll Let Myself In is her first book.