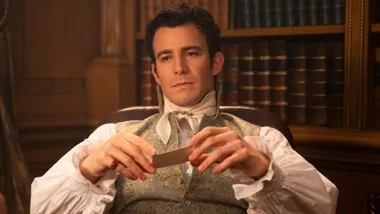

Photography by Theo Verhoeven

Words from a 70-year-old physician changed my life. It was a winter afternoon more than a decade ago, but I remember every detail vividly. I was driven to the appointment by my mum, and I was in disarray – both physically and mentally – when I arrived. A few months earlier I had been living in Sydney, working as a junior lawyer in a big firm, but now I was effectively unemployed and had spent the past four months living back with my parents at their home in northern NSW. I spent most days on their couch.

At the time, it felt like this change happened quickly: that one minute I was a fully functioning 24-year-old member of society, the next I was not.

“Georgie, I am so sorry for what you’re going through,” the physician said. He looked into my eyes and his gentle, sympathetic manner was more than I could bear. My own eyes welled with tears. “What you’re experiencing is real, Georgie,” he said. “In my medical career, treating patients for nearly 50 years, I have learnt that whenever there are unexplained physical symptoms, stress is always the cause. Always.”

That was the sentence that changed my life. The “unexplained” symptom in my case was vertigo: I had been unsteady and nauseous for months.

I’d had every test and examination to explain the debilitating dizziness that had been dogging me for months. It had started with a vertigo attack one night at work. I was knocked off balance and felt woozy. Once I arrived home to my apartment, I made a beeline for bed. I pulled a pillow over my face to block out any light, but also to hide. After a restless night, I took myself off to the doctor and so began my ride on the medical merry-go-round from hell.

Within a few weeks, I had moved back in with my parents and left my job. I couldn’t function with the dizziness. It wasn’t my first experience with illness. At 19, I’d been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, an autoimmune inflammatory bowel disease. Around the time the vertigo struck, my Crohn’s was particularly bad, but it was familiar at least. I knew how to cope with my wretched stomach, but I couldn’t manage my spinning head, so soon enough my world went with it.

No-one could give me an answer. That is until the elderly physician said I needed help. He wasn’t the first person to suggest anxiety was a problem for me – it had been raised gently by many of my loved ones – but he was the first person I believed. He said I needed to see a psychiatrist, probably start medication and be admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Realising he was right was shocking and relieving at once. For the first time, I had hope I might recover and that, at some point, I might be able to return to a version of life in which I was a participant, not an invalid on a couch. A week later I checked into a private psychiatric hospital and was treated for generalised anxiety disorder.

A few years after my breakdown, I wrote an article about it, which was published online. The response was so overwhelming that it buoyed me to keep writing. It’s no wonder my story struck a chord: one in four Australians will experience an anxiety condition in their lifetime – making it the most common mental health problem. It’s worse for women: one in three are likely to suffer an anxiety-related episode in their life.

Despite how prolific it is and the fact that we speak more openly about mental illness now than we ever have, there is still a stigma attached. This is the reason I wanted to write my book: to show that mental illness can happen even when you spend your life working hard to do all the right things. And, importantly, that it’s possible to be treated and recover. Anxiety remains an issue I have to manage, but my life improved immeasurably almost from the minute I realised I had it. Treating anxiety was far, far easier than leaving it unchecked.

Breaking Badly (Affirm Press, $29.99) is out now. This article originally appeared in the September issue of marie claire.