The gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians remains this nation’s greatest shame. A new approach is needed – urgently. The Uluru Statement from the Heart, signed by 250 First Nations delegates, finally provides a real roadmap for Indigenous constitutional rights. But for real change to happen, all Australians must join the fight…

When the police came knocking on Helen Eason’s door, she picked up her baby and ran with him in her arms. “I jumped fences and I tried to hide – I didn’t want to hand him over,” she says, tearfully remembering that dark day. “And when I did come back, they told me that they were putting him in care. I begged, I pleaded, I screamed. I threatened to take my own life. But he was gone. How could I go on?’’

Eason knew the feeling of despair all too well. Over a 10-year period on three separate occasions, all four of her older children had been removed from her care. The 44-year-old Gomeroi and Biripi woman had struggled with drug abuse and spent time in jail on drug charges, but she devoted her life to trying to reunite her little family in a system seemingly hellbent on keeping them apart.

“It felt like I had been beaten,” says Eason. “When they take your babies, they take your existence. It seems a neverending battle that we can’t win.’’ Even when her own mother stepped in and asked to take care of her grandson, her request was dismissed. Her mum – a respected community member, founder of Grandmothers Against Removals and a career nurse of 30 years – was deemed “unsuitable”, an assessment that Eason believes is typical of the bias and systematic racism at the heart of the removals.

Her children – who described the situation as like being “kidnapped” – were equally desperate to be back with their mum, aunts, uncles and cousins. “My middle boy ran away four times over three years trying to get back to me,” Eason says. “Then my little girl managed to find me. She was chased for three days by the police, who were trying to return her back to the placement. [Despite what they’d been through] the children never received any counselling or support. The attitude from the department is ‘deal with it’.”

But what happened to Helen Eason didn’t happen decades ago, it was in 2014, six years after Kevin Rudd issued an apology to the Stolen Generations (the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families between the 1890s and 1970s).

RELATED: Jess Mauboy on What Indigenous Recognition Would Mean to Her

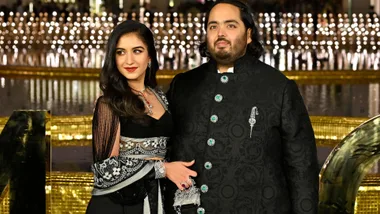

RELATED: Jesinta and Lance `Buddy’ Franklin on Why They’re Fighting For Change

Yet clearly the practice has never stopped. In fact, the number of Indigenous children in care has doubled since the 2008 apology. Today, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are 10 times more likely to be removed from their families than non-Indigenous kids. And it’s not the only statistic that shocks. An 18-year-old Indigenous man is more likely to go to jail than to university. And while Indigenous people make up three per cent of the population, they’re incarcerated at much higher rates, filling more than a quarter of our prisons. At one point in 2018, every child in detention in the Northern Territory was Aboriginal.

Our Indigenous youth have among the highest suicide rates in the world, and the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people is widening. Some Indigenous Australians refer to the inequity as the “torment of [our] powerlessness”.

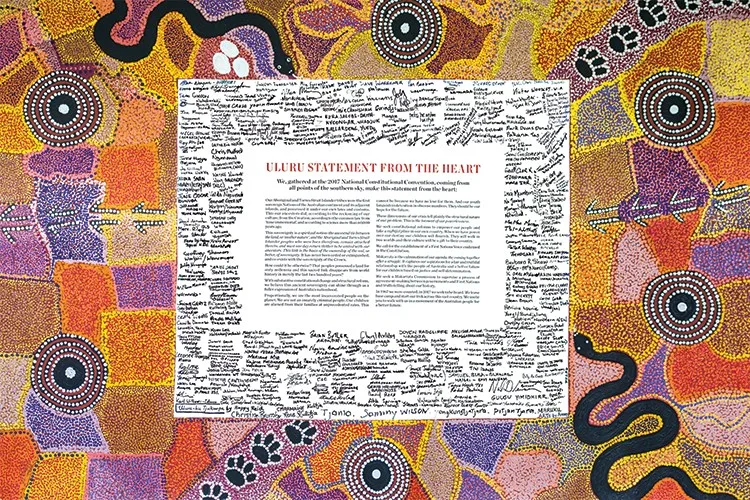

“The fact that Australia has failed to recognise Indigenous people’s voices in a meaningful way is an important explanation for why so many laws and policies have not worked over the years and why we are failing to close the gap in health outcomes and disadvantage,” says Megan Davis, a Cobble Cobble woman from Queensland, leading constitutional lawyer and professor at the University of NSW. Changing this, not symbolically but practically, is the primary objective of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. In May 2017, with Uluru as the backdrop, 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders gathered to present the Uluru Statement to the Australian public. It was greeted with a standing ovation.

It asked Australians to change the constitution to allow Indigenous Australians a meaningful voice in the laws and policies made about them (ultimately this would occur via a vote in a referendum). For decades, reconciliation, treaties and constitutional recognition have been debated but, Davis says, without “properly consulting the First Nations people on what meaningful recognition might look like to them”.

The Uluru Statement is different: it was the culmination of an unprecedented consultation in which 1200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives took part in a dozen dialogues across the country. “It was the first time Aboriginal Australia was widely consulted on the constitution, and the First Peoples reached consensus,” Davis explains.

“Voice”, “Makarrata” and “Truth” are the three principles Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people identified as necessary to repair and move forward together, as a united population. “Voice” means a constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice to parliament – potentially an elected representative body of Indigenous Australians who’d advise parliament on policies and laws affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. “Makarrata” is about bridge-building and treaties, while “Truth” requires a national process of truth-telling.

“We will all live together and make a new future for this nation, but it must be on different terms than those imposed on Aboriginal people for the last 230 years,” Gunditjmara woman, Jill Gallagher AO, said.

Aboriginal people have lived here for more than 60,000 years but are still not specifically mentioned in the constitution. Australia’s original founding document, adopted in 1901, failed to acknowledge Indigenous people’s prior existence on the land, though it contained several references that explicitly discriminated against them. In a referendum in 1967 the nation voted to remove those references, but nothing was put in their place. Australia is also the world’s only Commonwealth nation (besides Fiji and Botswana) that hasn’t ever signed a treaty with its Indigenous people.

These aren’t just theoretical legal problems. “The lack of recognition of Indigenous peoples in the constitution as [this land’s] traditional owners impacts on identity, perpetuating discrimination and eroding mental health and social wellbeing,” is how the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists explain it.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart underlines this disadvantage: “Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. Our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers.”

It is why too many families like Eason’s have been – and are being – torn apart. And it’s why Eason founded Nelly’s Healing Centre, to provide support to at-risk Aboriginal women and their families. “Healing from trauma, oppression and disadvantage is not possible without empowerment,” Eason says.

This theme of empowerment is at the core of the Uluru Statement. During the extensive consultation period, every group highlighted a sense of “powerlessness and voicelessness”, hence an enshrined voice to parliament emerged as a priority. Over the years, various bodies have represented the interests of Indigenous Australians in public policy, but it’s an area that has lacked consistency. What sets the proposed First Nations Voice apart is that it will be permanently and constitutionally entrenched.

This is a model that has been implemented around the world. Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and Finland are among the comparable democracies that have established a voice to parliament in some form. In New Zealand, there is still inequity, but Kiwis who identify as Maori are less likely to go to prison than Indigenous Australians and in relative terms earn considerably more each week than their Australian counterparts.

“If you involve the people a policy is aimed at or targeted at, it is more likely to succeed,” explains Davis. Now, she says, the risk of doing nothing “is too overwhelming to contemplate”.

Constitutional recognition is a crucial first step to bridging the gap, and public support is critical, as changing the constitution will require Australians to vote in a referendum. “This is why the Uluru Statement was issued, deliberately, to Australian people, not politicians,” says Davis. “It is a united population who can unlock the potential in a referendum and show politicians the way forward.”

What Can You Do?

1. Use the hashtag #ItsTime, tag @marieclaireau on social media, and write to us at marieclaire@pacificmags.com.au. We’ll compile your support and take it to parliament.

2. Read the Uluru Statement from the Heart and register your support at ulurustatement.org

3. Write to your local member of parliament and voice your support for the Uluru Statement from the Heart. It’s old school, but it works.

4. Speak to your colleagues, friends and family and spread the word about why this issue matters.

This article originally appeared in the February issue of marie claire Australia.