The 22nd day of the second month of 2022 had an air of fortuity about it, but for Jessica Van Nooten it started like any ordinary day.

The Melbourne-based chef went to work, came home and did some laundry. She was folding washing when she received a spine-chilling WhatsApp message. “Hello, your baby has been born unexpectedly,” it read. “She’s alive for the moment.”

Fifteen-thousand kilometres away in the Black Sea port city of Odessa, Ukraine, Van Nooten’s baby girl had been birthed by a surrogate mother. She’d come into the world 11 weeks early, weighing just 1450 grams. Her arrival marked the end of Van Nooten and her husband’s seven-year struggle to have a baby, but the start of another tumultuous journey.

“Kevin [Middleton] and I got together 20 years ago, when I was 18, and we always wanted children,” says Van Nooten. “We’re both chefs, so we travelled the world for work, and started trying for a baby when I turned 30.”

After trying to conceive naturally for two years, the couple went through 15 rounds of IVF. “That’s when our third and final specialist said no more,” recalls Van Nooten. “And he suggested we look into surrogacy.”

Van Nooten was initially hesitant to pursue the procedure—a form of assisted reproductive technology where a woman bears and births a child on behalf of a person or couple who are medically unable to conceive and carry themselves. But she joined a few Australian surrogacy Facebook groups and was shocked by the fierce competition. “For every one surrogate there were 90 ‘intended parents’. So why would they choose us?” remembers Van Nooten, noting that according to Australian law, surrogacy must be altruistic.

Their desperation peaking, Van Nooten and Middleton started to explore transnational surrogacy options. Commercial surrogacy, where the surrogate is paid for profit, is legal in Ukraine, Russia, Georgia, Kazakhstan and certain states in the US. Behind America, Ukraine is the second most popular foreign surrogacy destination in the world, with an estimated 2500 babies born via surrogate every year. There, intended parents pay about $50,000 – $75,000 for a surrogacy package (not including IVF costs).

“We decided on Ukraine because surrogacy is a big business there, everything seemed really above board and the surrogates are well looked after,” says Van Nooten. But before the couple could have their embryo transferred halfway across the globe, they had to get married, as Ukraine’s surrogacy legislation only supports heterosexual, married couples. Then, they were matched with a surrogate, Nina*, a barista who already had two children of her own. Van Nooten and Middleton met with her on Zoom, conversing via a translator.

Over the next few months, the couple received semi-regular WhatsApp updates from their agency, until the alarming birth announcement on February 22. In a flurry of panic, they booked flights to Ukraine and departed the next night. But on their stopover in Dubai, they received more gut-wrenching news: Ukraine had been invaded by Russia, and all flights into the country were cancelled.

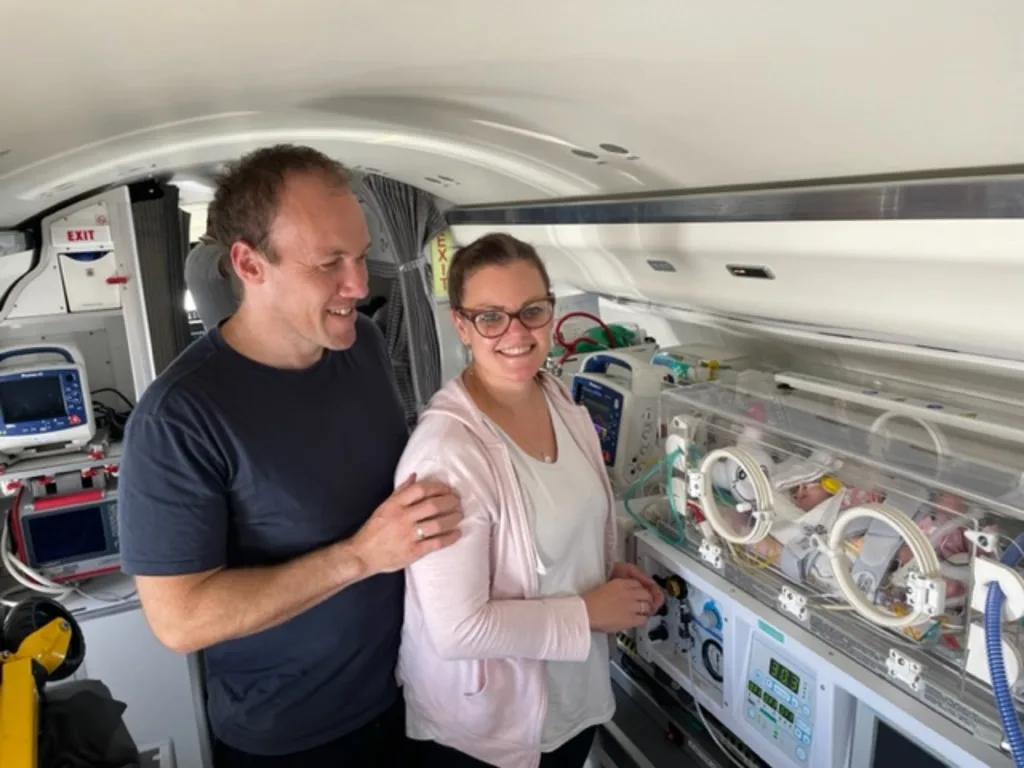

Van Nooten and Middleton spent the next two weeks on an adrenaline fuelled mission – travelling through Poland, Romania, Moldova and into the eerily quiet, soldier-lined streets of Ukraine. There in the hospital, they finally met their tiny baby, Alba, who was lying in a crib on a ventilator. “I said to her, ‘I’m sorry it took me so long,’” recalls Van Nooten. The couple were informed that Alba was suffering from a brain bleed, collapsed lungs and underdeveloped intestines. With bombs exploding in the vicinity, the family was transferred to a hospital in Moldova, and then medevaced to London where Alba underwent four brain surgeries at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Eleven weeks later, accompanied by a nurse escort, Van Nooten brought her baby girl home to Australia. At the time of writing, Alba is nearly seven months old (four months corrected). She wears a pink beanie, weighs 5.5kg and smiles sweetly as her mum cuddles her. “She’s just so special, and she’s definitely got some sort of Ukrainian fight in her … She’s meant to be here, Nooten, then pauses. “But we’d never do it internationally again.”

It’s estimated that for every baby born via surrogate in Australia (about 100 each year), three are born overseas. Along with Van Nooten and Middleton, between 20 and 40 couples from Australia had surrogacy plans in the Ukraine when the war broke out, jolting our laws into sharp focus.

Some contend that Australia’s strict legislation – and consequent shortage of local surrogates – is pushing intended parents into dangerous and sometimes illegal transnational arrangements. Yet opponents argue that surrogacy exploits vulnerable women and, when compensated, turns human life into a commodity. Commercial surrogacy is prohibited across all of the EU, and in 2018 the UN warned that it “usually amounts to the sale of children”.

“Surrogacy, and in particular compensated surrogacy, is a highly emotive issue,” says Professor Paula Gerber, who specialises in human rights law at Monash University. “People tend to polarise it into two extreme camps, either seeing it as exploitative of women or as a blessing for childless couples who want to begin a family.” A labour of love? Or wombs for rent? There are compelling

arguments on either side.

Last year, Shaun Resnik became the first single man approved to have a child through a surrogate in Victoria. For him, finding an altruistic surrogate was intensely challenging: he endured three soul crushing false starts, including being ghosted by one woman who’d agreed to carry his child. “You put your heart out there and you have so much hope,” says the 45-year-old, who’d always

aspired to be a dad and, as a gay man, saw surrogacy as his best path to parenthood. “And just like that, those hopes are dashed; it’s devastating.”

Eventually he met Carla, who’d become a friend early in his surrogacy “journey”. The high school teacher had three daughters of her own and had already been a surrogate twice before. “She rode in like a knight in shining armour and offered to carry my baby,” says Resnik, who is now the proud father to Eli, who was born in March.

One of the reasons Resnik pursued surrogacy in Australia is because he wanted his son to have a close connection with the women who helped create him. Carla and Resnik’s egg donor, Bree, both have a presence in Eli’s life, and the new dad says they all have a “wonderful relationship”.

While celebrities and scandals tend to dominate headlines about surrogacy, Resnik’s story paints it as a life-transforming modern fertility treatment, especially for gay and single men. But it still raises the question: why would a woman bear and birth someone else’s child altruistically? “I see it as a gift, the ultimate gift of life,” says Anna McKie, who was a surrogate – using a donor egg – for a gay couple, Matt and Brendan, in Adelaide two years ago.

“I had two young children of my own, and I’d really enjoyed being pregnant and giving birth, but [my husband and I] knew our family was complete. I also wanted to show my kids that if you have the capacity to help someone, you should probably try … People ask, what happens if you want to keep the baby? To that I say, if a surrogate wanted another child, there are much easier ways for her to have one.”

When McKie gave birth to baby Baker, Matt and Brendan rented an Airbnb five minutes from her home, so that she could breastfeed and have regular cuddles. She did, however, develop postnatal depression. “I knew in my head and my heart that I didn’t want to keep the child; I already had my own,” explains McKie. “But your body and your hormones don’t get that memo; they birthed the baby. They’re probably grieving the lost baby. Maybe it’s a bit like a stillbirth.”

With ongoing counselling (part of her surrogacy arrangement), McKie found her way out of the “dark pit” and today runs the Surrogacy Australia Support Service (SASS), hosting help sessions for the community. The potential health risks to surrogates are one of the reasons that Dr Helen Pringle, Associate Professor of Social Sciences at The University of NSW, opposes surrogacy in all forms.

“Pregnancy and childbearing is a wonderful experience, but it’s also very risky and dangerous for the woman,” she says. “We underestimate the strength of the bond that’s developed between mother and child before birth. To have the baby simply taken away is not respectful of the [surrogate] mother or the child, and I think it has long-term effects that we haven’t even started to understand.”

Surrogacy tends to divide liberal feminists along fault lines. One camp shares the viewpoint of Pringle, whose work centres on women’s human rights. But others assert that every woman, every would-be surrogate, should have the right to bodily autonomy. “She definitely should,” agrees Pringle. “But I think the question is: does another person have the right to use another woman’s body?

To buy and to sell her, to treat her like an object? I don’t think they do.”

Pringle also points to the broader societal structures that might lead a woman to “choose” to become a paid surrogate, highlighting parallels with the prostitution industry. “Rich people don’t usually volunteer to be paid for surrogacy,” she says. “Think about the former hubs of surrogacy before Ukraine: India, Cambodia, Thailand and Nepal. They all had characteristics of widespread poverty and … a lower status of women.”

In Ukraine, a surrogate will receive $15,000—$30,000 for her services, about three times the average national wage. She usually won’t work for the duration of her pregnancy, and is put up in modest accommodation. But as the Russian conflict in Ukraine escalated, surrogates, including Nina, were uprooted and separated from their families in a desperate bid to keep them – and the babies – safe.

Van Nooten met Nina at the hospital in Odessa, the two women communicating through shared tears and long hugs. “I said to her, ‘Did they [the surrogacy agency] look after you?’ And she told me they did,” says Van Nooten. “I asked her why she’d become a surrogate, and she said it was because it was easy for her and she could change someone’s life. She changed our life, and we changed hers. And we could change so many lives here too,” adds Van Nooten, hinting at what a compensated surrogacy model might look like in Australia.

Gerber believes that with careful consideration, paid surrogacy could be implemented safely and ethically on our shores.

“Transnational surrogacy is so high-risk and stressful that intended parents only do it as a last resort,” she says. “If we were able to allow compensated surrogacy in Australia, our first-class healthcare system [would better protect] the Partaking in paid surrogacy in Australia could result in a $110,000 fine and up to three years in prison surrogate and the child. And we would regulate minimum and maximum amounts of compensation, a minimum age, and have other safeguards in place [to avoid exploitation].”

Gerber adds that, by definition, a child born by surrogate is deeply wanted. “Think about how many [unwanted] births are going to happen in America since the overturning of Roe v Wade … With surrogacy, the intended parents have moved heaven and earth to have their child. This child will have a loving family.”

The risk, however, is that these deep parental desires supersede the best interests of the child or the surrogate. “Having a child is not a human right,” affirms Pringle, suggesting that rather than creating a surrogacy industry akin to Ukraine’s, we should rethink what parenting looks like. Long-term fostering or adopting differently abled children, for example, are both avenues for raising and caring for a child.

Of course the urge to reproduce—a complex blend of biological instincts and social conditioning—is often beyond logic or rationale. It’s what makes the surrogacy debate so sensitive and emotionally charged. Shooting stars, chicken bones, birthday candles … Van Nooten admits that she wished on them all as she yearned for a baby. “I feel so lucky to have Alba,” she says. “I just want her to have a good life. And hopefully the hardest part is behind her.”

This story originally appeared in the November issue of marie claire Australia.