Driving down the main street of Bowraville in Northern New South Wales is like taking a trip back in time. On the right side of the street is the cinema, where Indigenous people were forced to sit on a patch of dirt segregated from white patrons. Across the road is Bowraville Police Station, where three Indigenous children were reported missing in the space of five months in the early 1990s. On the outskirts of town near the rubbish dump is the Mission, a single street of red brick houses where the Indigenous families live and where all three kids went missing within 70 metres of each other. At the time, the street was called Cemetery Road.

Today, visitors to the mission are welcomed by a car sitting on cement blocks with its tyres removed and windshield smashed in. The bonnet and doors have been spray-painted in red graffiti that reads, “Fuck the police.” Back in the 1990s, everyone at the mission looked after one another. Kids played freely on the streets, but were warned by their parents not to leave the mission – afraid they would be hurt by white people.

On September 13, 1990, Colleen Walker-Craig, 16, was last seen walking away from a party on Cemetery Road. Three weeks later, Evelyn Greenup, four, went missing from her grandmother’s house on the same street after a party. Then on January 31, 1991, Clinton Speedy-Duroux, 16, disappeared from a yellow caravan at the mission where he was sleeping with his girlfriend after a party. Three kids. Three parties. Three disappearances.

Local police didn’t take the missing- person reports seriously. They suggested the kids had gone walkabout. Then Clinton’s body was found dumped in bush on the side of Congarinni Road, seven kilometres from where he was last seen at the mission. A pillowcase from the yellow caravan was found underneath his clothing. The caravan belonged to Jay Hart, a white 25-year-old labourer who had been seen at all three parties at the mission.

On April 8, 1991, Jay was arrested for the murder of Clinton, and later charged with the murder of Evelyn, whose body was found on April 27 in the bush near Congarinni Road with penetrating injuries to the skull – just like Clinton. Three years later, Jay, who had been in jail awaiting trial, was acquitted of Clinton’s murder, and the case against him for killing Evelyn was dropped.

After a 2004 inquest into Evelyn’s murder and the suspected murder of Colleen, Jay was charged again – this time just for the murder of Evelyn. The 2006 trial lasted a month but Jay, who has always maintained his innocence in all of the murders, was acquitted once again. It was a crushing blow for all the families but it didn’t stop their fight. For Jay to be put on trial again, NSW’s double-jeopardy laws needed to be changed – so that’s exactly what the families did, campaigning to have the legislation updated so any person acquitted of a life-sentence offence could be retried if important new evidence was uncovered. Yet in 2019, the High Court refused an application to retry Jay, concluding the new evidence was not “fresh and compelling”. Jay has since changed his name and moved from Bowraville.

For more than 30 years, the families of Colleen (whose body has never been found), Evelyn and Clinton have fought to right past wrongs.

This month, a new documentary called The Bowraville Murders is telling their stories. Three families. Three lost children. One ongoing mission: justice.

MICHELLE JARRETT

Evelyn Greenup’s Aunty

“I knew something was wrong straight away. I’d just gotten home from work when my sister Rebecca told me she couldn’t find her daughter Evelyn. She had put Evelyn and her little brother Aaron to bed the night before and they’d been looking for Evelyn all day. Aaron kept asking where his sister was and I remember him saying, ‘The bad man took Evelyn.’

I grabbed a photo of Evelyn to take to the police station; she was wearing a little check dress and looked like a doll with her curly hair and bright blue eyes. When I arrived at the station to report Evelyn missing, there was only one cop there. He looked at the photo of Evelyn and back to me, and said, ‘Well, what do you want me to do about it? I’m just about to knock off.’

I didn’t know what else to do. We started a search and put posters up all over town. We were desperate to find her, especially knowing Colleen had gone missing a few weeks earlier.

The town of Bowraville changed overnight. Growing up, it was a carefree place. We’d play outside all day until the sun went down. After Colleen and Evelyn went missing, everyone was scared and suspicious.

Six months after Evelyn disappeared, the police came to our house to tell us they’d found Evelyn. I had to tell my sister that her daughter was dead. I rushed to her house to tell her before she saw it on the 6pm news. She started screaming. My heart broke because there was nothing I could do.

Our family was devastated but our heartache was compounded by the fact we weren’t getting any police support. They sent someone to investigate the case, but it wasn’t until years later that we found out they’d sent a child- protection officer, not a homicide detective. They weren’t looking for a murderer, they were investigating our family. They wasted so much time.

It wasn’t until detective Gary Jubelin took on the case [in 1997] that a proper investigation started. It took Gary time to win our trust, but he was persistent, he asked questions and actually listened. If Colleen’s case had been taken seriously, Evelyn and Clinton might not have been murdered.

The police and justice system have severely let us down. In 2016, NSW police commissioner Andrew Scipione came to Bowraville and apologised. For any justice to happen, the cases of Colleen, Evelyn and Clinton need to be heard together. That’s why we fought so hard to change the double-jeopardy laws so Jay Hart could be retried. When he was acquitted, it was a kick in the guts.

Hope is the only thing that keeps me going. I’m hopeful we will find new evidence, that someone will come forward with information, that justice will be served. I’m not just fighting for Evelyn, Colleen and Clinton, I’m fighting for every Aboriginal family. This never should have happened to us, and it should never happen again. For more than half my life, I’ve woken up every morning thinking of Evelyn. We lost a member of our family, and there will always be a piece missing.”

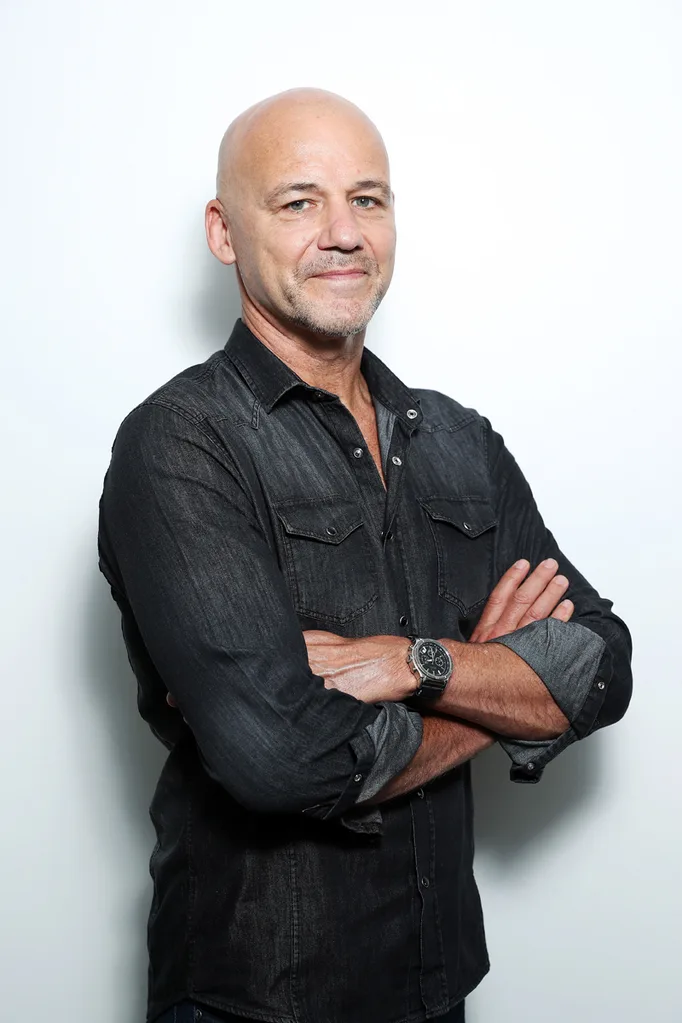

ALLAN CLARKE

Film director

“When I was a young kid growing up in Bourke, I went to stay with my uncle and aunty at the Mission in Bowraville for the school holidays.

We were told that three kids had gone missing and been murdered in the bushland, so we weren’t allowed to leave the ‘Mish’ or stay outside after dark. The story of the kids being taken terrified me and always stuck with me.

In 2019, I was approached by the producers of The Bowraville Murders documentary and came on board as the director. Returning to Bowraville and the street where the kids went missing was chilling. We wanted to tell the story of Colleen, Evelyn and Clinton, but we also wanted to show the horrific impact their disappearances have had on their families. Their grief is still as raw as ever, but their determination to get justice is unwavering. I think most people dealing with the trauma of murder would have laid down and never gotten up. So it’s extraordinary that the families are still pushing forward – after 30 years fighting the system, setbacks and racism.

It disturbs me when people compare this case to the murders of white children, because they’re all tragedies but everyone knows the stories of William Tyrrell, Daniel Morcombe and the Beaumonts. Yet hardly anyone knows about Bowraville, which is one of the worst killings of children in Australian modern history.

There’s an attitude in Australia that Aboriginal people are more likely to be perpetrators of violence, rather than victims of it. We still haven’t dealt with the atrocities that have occurred in this country or the inequity between Aboriginal people and the rest of the country.

I’m a Muruwari man, and when I was told about the murders as a kid I thought it could have been me, it could have been my sister or one of my cousins. This case mirrors the same issues in Aboriginal communities across the country. You won’t find one Aboriginal family that hasn’t had experiences with the police or judicial system. There needs to be changes within the system so this doesn’t happen again. The families deserve justice, and Aboriginal people deserve equality.”

GARY JUBELIN

Former detective

“I remember the first words Aunty Elaine [Colleen’s aunt] said when I arrived in Bowraville in 1997: ‘You got a lot to learn, white boy.’ She was right. I walked into town with the swagger of a big-city homicide detective, thinking I could line up witnesses and interviews. The families told me from the start that people did not care because they are Aboriginal. I naively thought they were wrong, but they were so right. I had white people in Bowraville comment on the case. Someone said, ‘Why are you wasting your time on finding out who killed the kids? You’d give them a medal if you found them, wouldn’t you?’ It’s this racism and unconscious bias that the families have been battling for 30 years.

Mistakes were made in the initial investigation because the disappearances were looked at in isolation. The warning signs of a serial killer should have been spotted, but they weren’t because the police assumed the kids had gone walkabout. Looking at the evidence now, it would be ludicrous to suggest the crimes weren’t linked.

I worked with a forensic psychologist on the case, and we found a motive for all three murders: sexual gratification. [Colleen had been subject to sexual advances from Jay several weeks before she disappeared. Evelyn’s mother, Rebecca, woke up in the room she shared with her daughter to discover her pants pulled down and her daughter gone. Clinton’s girlfriend Kelly (Jarrett) woke up in Jay’s caravan to find her underwear had been removed and her boyfriend had disappeared]. It’s clear the killer was prepared to dispose of anyone who got in the way of what he wanted.

It’s frustrating the three murders haven’t been heard together as one case. If the evidence was presented together, I have no doubt the jury would find the suspect guilty. After the acquittal in 2006, the families fought to have Australia’s double-jeopardy laws overturned and they won, which was an amazing achievement. It meant that Jay could be retried. Unfortunately, in 2019, the High Court dismissed the appeal for fresh evidence. That was a hard day. The families looked to me for strength and answers, but I had nothing but sadness. We had all invested so much hope in the appeal, and we were left broken by the decision.

Aunty Elaine always used to say, ‘Justice comes in many forms.’ If we can’t get justice through the courts, we’ll keep pushing for it elsewhere. An inquest could give the families the answers they’ve been searching for. In the meantime, this story needs to be told and hard lessons need to be learnt.”

JASMINE SPEEDY

Clinton Speedy-Duroux’s cousin

“Clinton’s nickname was ‘Bubby’. He was a beautiful, gentle soul who made everyone laugh. Kids were drawn to Clinton, and he always had a line of little ones trailing him. I still remember hanging off his leg while he tried to walk around. I was four when Clinton was murdered, but I’ll never forget the day he went missing or the day his body was found. I can still see my family wailing and crying as they watched the news and saw his remains being wheeled from the bush in a body bag.

Those scenes replayed in my mind in 2006 when Jay Hart was acquitted of Clinton’s murder. My grandmother lost her shit outside the court. It was the same reaction we had when Clinton’s body was found: grief, anger, trauma.

I’ve been involved in the fight for justice for 20 years: attending inquiries, marching in rallies. My sons are 17 and 14, and they’ve joined me at the protests. My boys are about the same age as Clinton was when he was murdered, and they’re dealing with the intergenerational trauma of that. What happened to Clinton is always in the back of my mind. If my son doesn’t answer his phone, I automatically think the worst.

The trauma of Clinton’s death is always there. Clinton was more than a murder case. He was our Bubby and that’s how we remember him, dancing to Michael Jackson and making us laugh.”

There is a $1 million reward for information leading to a conviction over the murders.

This story originally appeared in the November issue of marie claire Australia, out now.