In 2003, aged just 27, Samantha Brand, a newly qualified midwife, found out she had stage 3C ovarian cancer. She was given just five months to live and her life instantly became about chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy. Against all odds, Sam survived and has been in remission for 15 years. The most lethal women’s cancer in Australia, ovarian cancer often goes undetected until it’s almost too late – those diagnosed have a 45 per cent chance of surviving past five years (compared to 90 per cent for breast cancer). Approximately 1,600 women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Australia every year.

To mark Ovarian Cancer Awareness Month, Sam shares her story.

In July 2003, I was 27 and a newly qualified midwife at a local hospital in the Mornington Peninsula. I’d been in the position I was in for two years when I started getting abdominal pain, which was starting to irritate me. Because I have a bit of an irritable bowel, I put it down to that and so although I had other symptoms, including heartburn and reflux, I didn’t think there was anything serious going on. I started getting abdominal bloating and also some deep pelvic pain, where I was struggling to lift things, so after around a month of putting it off, I went to my GP and said something wasn’t right.

My GP put it down to my appendix, but the pain had been going on for weeks by this stage, and I knew my appendix definitely would have burst by then. I was due a pap smear and I asked to be swabbed for other things, such as STIs, too. The results showed I was growing an organism which causes pneumonia and is a systemic infection. Little did I know, it was because I was immunosuppressed: I had cancer. The doctor put me on antibiotics thinking I had a pelvic inflammatory disease, but over the next two weeks, the pain became more and more severe. The antibiotics weren’t helping and I was beginning to lose my appetite and, at times, vomiting.

I went back to the doctor and pushed for further tests, telling them, “No, something is really, really not right with me.” I got a direct referral to a gynaecologist that day – a colleague of mine – and she did an examination, saying straight away that she felt a mass and that I needed to have an ultrasound. They thought I had a dermoid cyst (a rare cyst that can grow teeth and hair) and scheduled me for surgery, but because they are generally benign, at that point I wasn’t too worried. The only thought worrying me was that I could potentially lose my ovary, but it calmed me knowing I had another one, should that happen. I went straight from the ultrasound to the ED department, which is where I actually worked in the hospital, and signed the consent, which said that I might have to have my ovary removed. I remember arguing with the doctor because I didn’t want to lose an ovary. Little did I know, I was in for much worse than that.

I was in surgery for five and a half hours and when I woke up, I had a PCA for pain relief and a full incision from one side of me to the other. Straight away, I knew something was wrong. I asked anyone near me every question I could think of: “What’s going on? What happened to my ovary, what happened to the surgery?” It was very early in the morning and I was very groggy, but I could tell everyone was acting strange – treading around me carefully. My mum, dad and my partner at the time wanted to let me sleep and explain everything in the morning, so I demanded that one of my colleagues explained what was going on. That’s when I found out that they opened me up routinely to get rid of an ovarian cyst and they found that my abdominal cavity was completely full of what they suspected was cancer. I couldn’t really take in what I was hearing. My boss came in to see me afterwards and I said, “I think I have cancer”, she was probably one of the first people to say, “Yes, we know.” I found out later that they didn’t actually know what they took of my organs during the surgery, because I was such a mess inside and they couldn’t distinguish my anatomy. They thought they’d taken both of my ovaries, but couldn’t be sure. I went from arguing to save one ovary, to telling them to take whatever they needed in order to save my life.

I was told I had about a five per cent chance of surviving.

I was then moved to another ward and seen by a surgical oncologist, whose name is Tom Jobling – he’s probably the best person in the world, he’s my hero. Upon meeting me, Tom said, “You’ve got a massive fight on your hands.” He explained that they had to wait for the pathology to come back, but they strongly suspected that it was cancer. They were right, and it was stage 3C. Tom told me he wasn’t going to give up on me, but that it was going to be a really difficult, long road and with the type of cancer I had, I’d be lucky to make it to Christmas. It was July.

Treatment

We waited for a week for my wounds to heal before Tom said, “Right, we needed to start chemo yesterday.” I went straight into chemo for six months. For me, the chemo was worse than the disease itself. It hit me really hard. I had a combination of three different types of chemotherapy – two types one week, another the next and then I had a week off, it was really, really, intensive chemo. I went into it quite strong and I came out of it a train wreck.

When Christmas came and I was still alive, they scheduled another surgery, during which they took all of the residual tumour away and decided to preserve my uterus because it wasn’t affected. But when the results came back, I was told I had some microscopic cancer left. I was really shattered.

I thought it was over, that I’d defied the odds, that I was still alive and that it had gone – it hadn’t. There were arguments with the doctors about how to manage me at that point. Tom wanted to keep fighting for me and, though he said it was a longshot, give radiotherapy a go. The oncologist, however, advised me against radiotherapy and when I asked what that meant, said, “We’ll just wait for the cancer to come back and we’ll palate you,” which is a way to say, we’ll just manage you until you die.

My hero, Tom Jobling, pushed for the radiotherapy, which went on for 35 days every day, but I was told I had about a five per cent chance of surviving. Because I wasn’t recovered from the chemo when I had surgery and then radiotherapy, it really took its toll, it took a lot out of me. The past 10 months had been filled with surgery, chemo, surgery and radiotherapy. I was exhausted. After the 35 back-to-back days of the radiotherapy, Tom actually said to me, “Sam, I think we’ve got it. I think, at the moment, you’re cancer free.” That was in May 2004 and I’ve been in remission for 15 years.

Tom refers to me as his little miracle and every time I see him he’s absolutely blown away that I’m still here. Going through that changes your outlook on life completely, every day I wake up and think, ‘Wow I’m so pleased to be here still.’

Children

When I had the first surgery, they had no idea whether I still had an ovary inside me so they sent me to a fertility specialist to discuss my options. At the time, she said they could try to harvest some eggs because once you have chemo your ovaries will no longer be able to function. I went to Tom and he basically said, “Do you want to harvest your eggs or do you want a shot at surviving?” I answered, “I think I want to live” and he said, “Well, let’s not harvest your eggs because we’re having chemo next week. We can’t put the chemo off for one second if you want a shot of survival.” It was quite devastating knowing that I didn’t have a choice – my choice was, you either highly increase your chances of living or you decrease your chances of living.

Because they’d saved my uterus, I knew that in the future it might be possible to get a donor egg. I rekindled my relationship with my now husband, Ben, who I’d dated for three years from age 21, and we married. After five years in remission, I was 32 and realised I was ready to have a baby. I was referred to a fertility specialist, Kate Stern, who deals with people like me who are very complicated, and she did tests on my uterus, which came back positive. She thought there wouldn’t be a problem getting me pregnant. My sister offered to donate her egg and I had three embryos implanted in me, without success. Another friend of mine then offered to donate her eggs and I had another four embryos implanted in me without success. We ended up moving to Spain for six months to go through a donor egg program. I had eight tries there without any success, I never got a pregnancy. The clinic in Spain suggested there might be something wrong with Ben’s sperm, which was another blow for us. So basically, I was being implanted without mine or Ben’s genetic material. We came back to Melbourne and were really devastated, deflated and broke. By this point, we wanted children so badly that I was planning to save money and go back to Spain. I became so numb by this point, every time I lost one it was just, “oh, another one gone,” because of the way it makes you feel, I just lost count. Having had cancer before and having high dose hormones, you propose a risk for the cancer to return. I was taking massive amounts of hormones, but I felt it was worth it.

My two sisters then came to us and said, “Sam, we can’t watch you do this to yourself and your body and see what it’s doing to you and Ben. We’ve decided that we’re going to help you out.” My 21-year-old sister at the time, Nikkita, and my 32-year-old sister at the time, Rachael, told me that Nikkita was going to donate her eggs, Rachael was going to be the surrogate and we were going to use Ben’s sperm. We went back to Kate and she said that there might be a few hoops to jump, but she thought she could get it over the line. Because Nikkita was so young and hadn’t had children before, she had to go to the ethics committee and get psychological testing done. She got through that and donated her eggs twice, Rachel became our surrogate and she had our baby, Starla, for us, who is now two-years-old. Our little miracle.

The takeaway

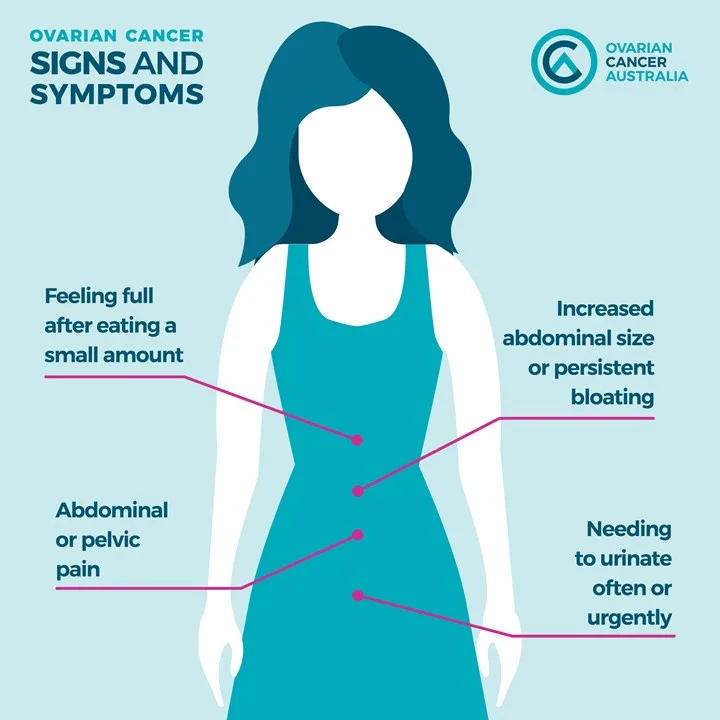

I was everything ovarian cancer wasn’t: I was young, fit, healthy, it wasn’t in my family. I just didn’t fit the category at all. If something doesn’t feel right, you need to jump on top of it and get checked – get a second opinion and push for people to take you seriously. The more people are aware of the symptoms of ovarian cancer, the better. Trust your gut instinct, it’ll tell you if something isn’t right. It’s a silent killer and sometimes doesn’t start causing issues until it’s too late, so understand your body and know what’s right and what’s not right.

Ovarian cancer symptoms

For more information about the signs and risk factors visit www.ovariancancer.net.au. You can also show your support by purchasing a teal ribbon on Teal Ribbon Day on Wednesday, February 27.