There’s a saying you might have seen written on a letter board outside a church or tattooed on some bloke’s chest at the local pub. It’s a profound sentiment: “We’re born with nothing, and we die with nothing.” In theory, the statement rings true. In reality, though, most of us will die with stuff — lots and lots of stuff.

The average American home has 300,000 items in it. The average UK child has 493 toys by the time they turn 13. And the average Australian person buys 56 new items (or 15 kilograms of new fashion and textiles) each year.

It’s a lot to leave behind.

This thought is driving a new wave of minimalists who are planning to die without belongings. Our possessions in life can become burdens in death, as many of us who’ve lost parents have found out the hard way.

“My dad passed away when I was 19, and as the oldest child I was in charge of everything,” says Renee Benes, who’s now 36 and runs the minimalism blog, The Fun Sized Life.

“He had an entire storage locker full of things and I had to clear it all out. I inherited my great-grandma’s Bible from my dad. I hung onto it out of obligation and kept it tucked away in a drawer. When I started on my ‘minimalism journey’, I realised that storing something that wasn’t being used or enjoyed — for the sake of it — was just wrong. So I donated the Bible to a charity shop.”

While it might be hard for some to comprehend giving away a precious family heirloom that’s been passed down through generations, Renee isn’t the only person ending the cycle. More and more of us are planning to leave nothing materialistic behind.

Why? Good question.

“There are a number of reasons people are turning to minimalism,” says Rebecca Blackburn, a PhD candidate at the Australian National University in Canberra researching the environmental impact of living

a minimalist life.

“The reasons that come up the most include wanting to have less clutter and to feel less overwhelmed about the time and money spent on buying, cleaning, repairing and maintaining things. There are also environmental motives, wanting greater flexibility to travel and a general dislike of consumer culture.”

Renee falls into the first category. Her journey from shopaholic to minimalist started in 2014 with her wardrobe. Back then, she owned dozens of pairs of shoes: a floor to ceiling rack of heels, shelves of winter boots and sports shoes, and a bin full of summer sandals in every colour.

“I was drowning in stuff — too much stuff — and it was giving me anxiety. I just wanted to shake free from it,” says Renee, who culled her closet, sold her “dream” home, reduced her bills and paid off debts. That was nearly a decade ago. Now, she’s never been happier.

Research published by the International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology in 2020 reported the benefits of living with fewer possessions. Minimalists were found to have a greater sense of autonomy, more mental space and positive emotions including joy and peacefulness. It sure sounds good.

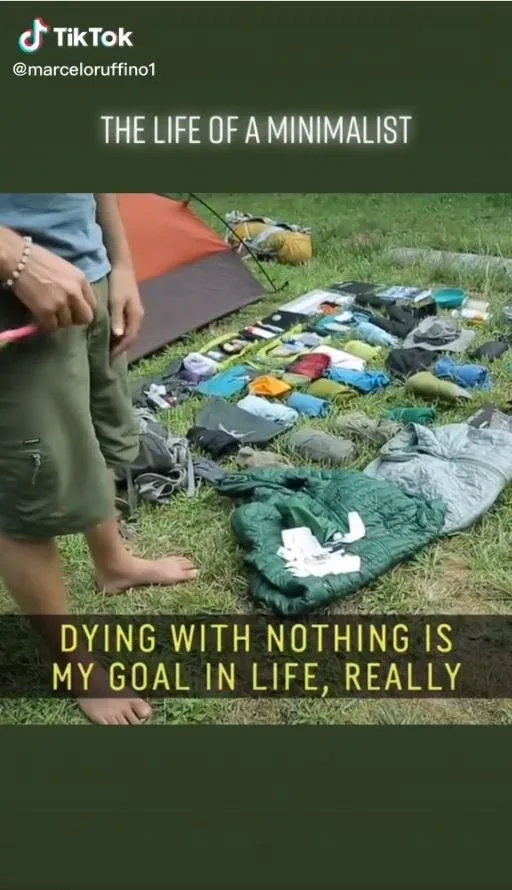

But like all good things, some people take it too far. Last year, a TikTok user named Marcelo Ruffino shared a video of a man explaining how he lives with 44 possessions. “Dying with nothing is my goal in life. I don’t have a car, no bank account or credit card and no cell phone. I eat nothing packaged or processed but instead herbs and greens that I forage and occasionally a deer that’s been hit by a car,” the man says in the video, while packing his belongings (including a laptop) into a backpack.

“Minimalist with a MacBook [cry-laughing emoji],” reads a comment under the video.

And there you have it, the other reason for going fully minimalist: TikTok fame.

“I suspect the people who do take minimalism to the extreme do so because it makes for good social media content,” says Rebecca. “More than 10 years ago, there was a man named Dave Bruno who famously tried to live with just 100 possessions. I wonder what he’s like now and if he was able to maintain that lifestyle after he published his book on the topic.”

There’s a difference between being a minimalist for yourself, your family or the environment, and being a minimalist for social media stardom, or the “aesthetic”.

As someone who practises what she researches, Rebecca considers herself to be a “minimalist” but not “an extreme one”. Her story starts in the mid-2000s when Rebecca and her husband moved from Canberra to the Cook Islands to work with Australian Volunteers International. They reduced their possessions to fit into two backpacks, and also took a bike each and an old computer.

While there, “My husband and I lived in an A-frame house with a simple kitchen and living area downstairs and two small bedrooms upstairs. It was just the two of us, so it was fine,” recalls Rebecca. “Next door to us was an identical house with five people living in it.

Our neighbour, a four-year-old girl, came over to our house one day and had a look around. ‘Geez you guys have a lot of stuff,’ she said about our culled belongings. She was right.”

That was the moment Rebecca began to consider her environmental footprint and take an interest in the low-consumption lifestyle. Now, living back in Canberra, her home is “pared down” — with the exception of plants and pieces of art.

“In the kitchen, I only have one set of bowls and one set of saucepans, and in my wardrobe I have a quarter of the number of clothes I used to,” she says. “I really hope to not have [possessions] when I die. I don’t want to make a burden for anyone.”

Much like Renee, Rebecca came to this realisation after the death of a parent: “When my mum died a couple of years ago, I spent a lot of time with my dad dealing with her possessions. That changes your perspective on holding onto things.”

Once that perspective changes, both Renee and Rebecca say the process of letting go is pretty pain-free.

“If you’re indecisive about disposing of something, put it out of sight. If you don’t go looking for it within six months, then you’ll know you can live without it,” says Rebecca. “You can give things to friends and family, sell things on Gumtree or Marketplace or give them away on Buy Nothing Facebook groups.”

Somewhat more philosophically, Renee advises wannabe minimalists to first look inwards. “Ask yourself how you want to have spent your time at the end of your days. Do you want to have built the best shoe collection or do you want to have spent time with your kids?” she says. “Make space in your life for the life you want.”

Carey* is only 54 years old, but when she dies she doesn’t want a funeral. She wants a bonfire. “I want anything that’s left of mine to be burnt,” says the self-proclaimed wanderer, who has moved more than 30 times in her adult life. “Every time I move, I sell everything — or give it away — and start again. Material things just tie you down.”

As a single mum who buys goods only at op-shops, minimalism is a necessity. Carey had to get used to surviving on very little while raising her son on her own. “We didn’t have a lot of stuff because we couldn’t afford to — not because it was trendy,” she admits.

While dying without possessions might be a trendy goal for some, it is a reality for others. The difference between minimalism and poverty is choice. Carey might not have chosen to live with the bare minimum if she didn’t have to, but she is choosing to die with the bare minimum.

Today, she lives in a tidy apartment in regional NSW with only the basics. She doesn’t own a computer or a laptop, has never used a microwave and has a phone only to stay in touch with her now-adult son. Carey takes solace in knowing that when her time comes she won’t be leaving her son with “piles of shit to sort out”. Rather, she’ll be leaving him with a small pile of shit to burn.

Flames are also on Renee’s mind. “My whole house could burn down and I truly wouldn’t think much about it,” she says. “Sure, I wouldn’t be thrilled. I love my house but I’m detached from the things inside it. That’s a really liberating feeling.”

*Name changed.

This story originally appeared in the May issue of marie claire Australia.