Chances are, if you’re familiar with Dasha Nekrasova, you either love her or you hate her.

As the co-host of podcast Red Scare, she’s established herself as one of the most compelling and controversial cultural critics of today alongside co-host Anna Khachiyan.

Whether it’s getting repeatedly “cancelled” for comments they make on the pod, guests they invite on (they once interviewed Steve Bannon much to the chagrin of liberal Twitter) or merchandise ideas gone wrong like the time they launched an “ISIS-themed” t-shirt range, rarely do people feel indifferent about Nekrasova or Khachiyan if they know who they are.

Alongside her role as podcast provocateur, Nekrasova works as an actress, having appeared in films and television such as the latest season of Succession. Now, with the psychosexual thriller The Scary of Sixty-First, she makes her feature film directorial debut.

With Madeleine Quinn, Nekrasova wrote the script after becoming “obsessed” with the alleged suicide of Jeffrey Epstein.

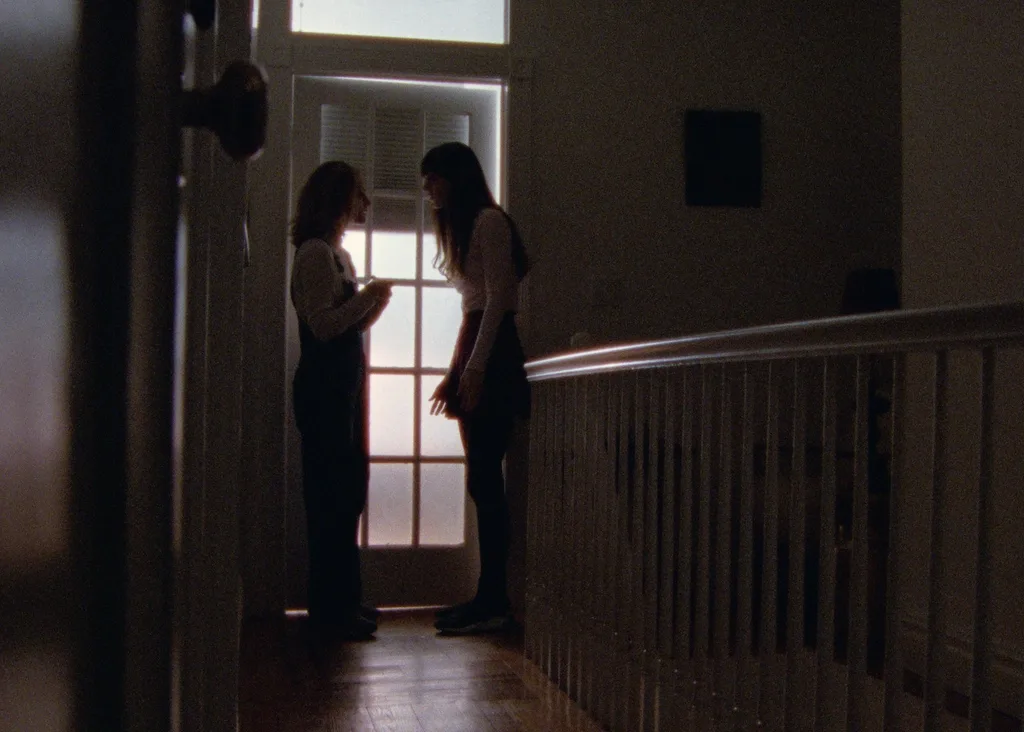

Scary follows two friends, Noelle (Quinn) and Addie (Betsey Brown), who manage to secure the lease of an insanely nice New York City townhouse. It’s so nice, in fact, that it seems a little too good to be true. Turns out, it is.

With ties to Jeffrey Epstein and his sex trafficking operation, the apartment is haunted in more ways than one. After a conspiracy theorist (Nekrasova) shows up at their door posing as a realtor, things kick off in this horror film that has a sardonic sense of humour and exists in the same universe as Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut.

It premiered at the 2021 Berlin Film Festival, where it won Best First Feature and will be released in Australian cinemas on December 16.

Here, we chat to Nekrasova about how the film came about, how it serves as her homage to director Kubrick and why she wants people to think more seriously about the crimes of Epstein and what they reveal about the sinister upper echelons of society.

marie claire: You’ve been acting for a while now, was it always the plan to direct as well?

Dasha Nekrasova: Um, no, I had vague ambitions to. I sort of thought that directing is something I would like to do one day, because I had acted in so many low-budget films that are made pretty collaboratively anyway.

And I had ideas and I’d had screenplays that I tried to write in the past. But I sort of thought it was something I would do down the line. We initially started writing Scary as a short and I even said to my co-writer, Maddie, ‘do you think that I could make a feature film before I’m 35?’ And then when Scary turned into a feature, she was like, ‘You I did it way sooner than you thought’.

mc: Can you talk me through the genesis of the idea?

DN: I was really obsessed with the Jeffrey Epstein stuff. When it happened, I was living very close to the prison where he died and it was a major event. It sort of set me off on a little bit of a manic spiral. It was such an egregious example of total corruption and injustice.

So I was really obsessed with it. And that energy was being channelled into various things; I was having Epstein truther meetups in Union Square Park, I was talking about it, thinking about it, reading about it all the time. As was Maddie. And at some point, we thought maybe the best way to channel this productively would be to make a film. So that’s what we did.

mc: There’s a genre within horror that treats spaces and architecture as kind of like, inherently haunted. I think Scary plays in that tradition with New York and the role or impact that Epstein had in real estate. Can you talk a little bit about that and how you approached it?

DN: Well, the townhouse or the prison had a very powerful aura to me, I would go walk by it a lot and think about it a lot. It’s a really awful prison and he’s the only person to have allegedly committed suicide, because it’s maximum security.

Then the townhouse, obviously, is this insane vessel of wealth and evil. All these terrible things happened there, and it has such an impressive and frightening facade that it did feel like a very charged space and so that was another site in New York that I would visit a lot.

Then of course Epstein himself being very influential in real estate being a financier, having all these connections to the city, really did just make it seem like a natural way to tell a hauntology, basically, and the apartment the girls move into, which is not a real place, but that was that was the idea. When we started shooting my DP, Hunter Zimny, and I really noticed a lot of the gargoyle architecture on the Upper East Side.

And that’s the opening sequence in the film is us walking around being like, ‘whoa, look at that weird gargoyle…it just seems super evil.’

mc: There’s obviously a lot of explicit references to Stanley Kubrick and his films, as well as stylistic ones to Polanski. Can you talk me through kind of like those explicit references? Maybe specifically the intertextual references to Eyes Wide Shut, with the letter in the final scene? Because that places your film within the universe of that one. Can you kind of unpack that? That’s obviously a very explicit decision.

DN: With the Polanski, I am a great fan of Roman Polanski’s. So those influences were, you know, stylish and with Polanski, definitely structural because in his Apartment trilogy, he’s basically telling the story of someone in an apartment where something is going wrong.

As for Kubrick, always since the inception of the film, we were we’re going to invoke that trope of have a letter, and then I felt like it should just be the real letter, because that was so good. So yeah, then it engages with Eyes Wide Shut on this meta level.

Eyes Wide Shut has sort of had a resurgence as well in the last few years and people have understood it, especially post-Epstein, in a way that they didn’t understand it when it first came out, because everyone just saw it as this like erotic or marital drama that like was falling a little flat for people. But what it’s really about this overarching elite power structure that Kubrick deals with in all of his films in some way.

He was very interested in power, and he knew a lot about it, particularly that it was incredibly dangerous, which is why he left Hollywood, which is why he lived in the UK. So, the movie has nothing really formally to do with Kubrick, but it’s dedicated to him.

It’s in homage to him, because I wanted to, I don’t know, honour his vision of the world. He knew something about the world’s worst secret, which is that there are these incredibly evil power structures.

mc: I feel as though that’s also probably why the Epstein stuff resonates with a lot of young people because it does expose this, like, the ruling class as incredibly corrupt. I wanted to ask as well, I read that Addie’s character arc was influenced by some ethnography that you read about female factory workers in Malaysia. Can you elaborate on that and how you applied it to her character?

DN: Yeah. It’s a book that I read in college that really stuck with me called Spirits of Resistance in Capitalist Discipline. It was about how there was an epidemic of spirit possession amongst female Malaysian factory workers like in the 70s, or 80s when it was starting to become industrialised. And it tells that story in a very interesting anthropological way that doesn’t just treat it as like psychosomatic, insanity or something. It was like, there was something about Malaysian culture that was directly at odds with capitalist discipline, and capitalist infiltration, this occurred because the cognitive dissonance of those things. But in that way spirit possession is its own kind of resistance, because they would completely halt production when they would start seizing on the factory floors. And they would have to shut down the factories for days and have Malay shamans come in and slaughter a goat so that they could like resume working, because they were convinced that these factories were evil places, which, you know, they sort of were.

And so Betsy becoming possessed and the way it plays out in the film, my idea for it was that it would be a kind of resistant activity. Because you’re talking about paedophilia, and it’s really about taking those desires, and making them like grotesque, and disruptive. And Betsy portrays that so well, there’s so much rage in her performance and it is disturbing to a lot of people.

mc: When you’re making the film or writing it, did you go into it wanting the audience to take something away? A message or anything other than, I guess, Epstein didn’t kill himself?

DN: Yeah. Other than that, like, the reality depicted by Stanley Kubrick and Eyes Wide Shut is worth interrogating. And, yeah, I mean, I guess I had a feeling that there would be a lot of Epstein media that would come out which sort of has with like, the Netflix documentary and stuff that would kind of whitewash over the aspects of corruption and kind of make it into kind of like a salacious sex True Crime thing. And so I wanted the movie to be a record. I have like, an emotional truth about the Epstein stuff that I didn’t want to be, like, eradicated or whitewashed. I wanted it to like exist as an artefact of like, a way that I felt in this in this in this period. Yeah. And even though I felt crazy, it was always it was the only rational response.

The Scary of Sixty-First is in cinemas December 16.