The energy in the stands at the Sydney Olympic Stadium is fizzing with electricity.

The air is thick with anticipation, hope and serious competitive spirit.

Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, oi, oi, oi! It’s our first Olympics in 44 years and this is the moment we’ve all been waiting for: the women’s 400-metre final.

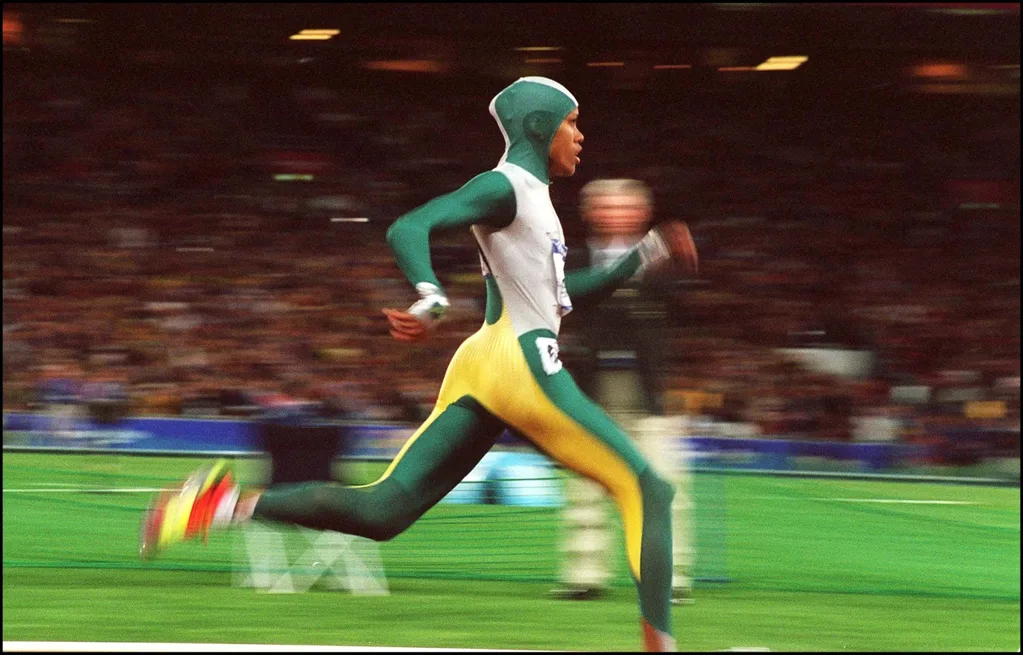

All eyes are one person: Cathy Freeman. She’s jogging on the spot at the starting line, wearing a futuristic, aerodynamic, green-and-gold Nike suit and a face full of determination. Four words are running through her mind on repeat. “Do what I know,” she tells herself. “Do what I know.”

As the athletes take their places in their lanes, the American commentators set the scene: “Cathy has been waiting for this moment since ’96, Australia has waited for this moment since ’64, the Aboriginal people have waited forever.”

On your mark. Get set. Go! When the starting gun fires, the stadium erupts with flashes of lightning. Except it isn’t lightning, it’s the flashes of thousands of cameras wanting to capture this moment.

And what a moment it is. In 49.11 seconds, Freeman makes sporting history in lane six. She strides ahead of her competitors and takes first place in a blaze of glory. She’s done it. She’s won. And she’s become the first Aboriginal athlete to win an individual Olympic gold for Australia.

At the finish line, when Freeman breaks down in tears, Australia cries alongside her. When she does a victory lap, flying both the Australian and Aboriginal flags, we cheer her on, “our Cathy,” our golden girl.

As sporting moments go, they don’t get more iconic than that race in 2000. Freeman’s entire life and career had been working up to those 400 metres. As a kid, her mum made her write “I am the world’s greatest athlete” on a poster to hang on the wall.

She’d dreamt of winning this race for so long that when it actually happened it didn’t feel real. “I’m just a little Black girl who can run fast, and here I am sitting in the Olympic stadium, with 112,000 people screaming my name,” she wrote of the legendary win in Cathy: My Autobiography in 2004.

The moment was historic on for a nail-biting loss to Marie-José Pérec at the 1996 Olympics. It was a statement after Freeman was brutally criticised for being “too political” by carrying the Aboriginal flag after her Commonwealth Games win in 1994.

It was a childhood dream come true and an inspiration for generations to come.

Catherine Astrid Salome Freeman was born on February 16, 1973, in Mackay to Cecelia Barber (a Kuku Yalanji woman from Far North Queensland) and Norman Freeman (a Birri Gubba man from Woorabinda).

Her father earned the nickname “Twinkle Toes” because of his agility on the football field – a sporting trait that was passed on. The family included Cathy’s brothers Gavin, Garth and Norman, and older sister Anne-Marie. Anne-Marie was born with cerebral palsy and sadly passed away from an asthma attack in 1990.

Like many times in Freeman’s life, her success was interwoven with tragedy: Anne-Marie’s death came just days after Cathy won her first gold medal, at the Auckland Commonwealth Games.

Then, in 2008, her brother Norman, also a champion junior athlete, was killed in a car accident in Mackay, while another brother, Garth, had to be cut from the wreckage. Cathy found out about the accident at Brisbane Airport while she was transiting between flights to visit schools for the Cathy Freeman Foundation, which she had launched in 2007.

Family was an important part of Freeman’s running journey. Her very first “gold medal” was at a school athletics carnival when she was eight years old. Freeman’s stepdad, Bruce Barber, coached her in school athletics until she moved to Kooralbyn International School to be coached professionally by Mike Danila. The tough training paid off when Freeman became the first Aboriginal woman to win gold at the Commonwealth Games, in 1990 at age 16, as part of the 4 x 100m relay team.

In 2003, Freeman reflected, “Running for me is always more than just physical and mental; it is also emotional and spiritual. You can draw energy from the universe, the stars and the sun, everything around you.

You can draw energy from what has happened in your life.” Freeman drew energy not just from her own experiences but from her family history. Her grandmother was part of the Stolen Generation, forcibly taken from her family at eight years old.

She also drew energy from the racism she faced as an Aboriginal elite athlete. After her win at the 1994 Commonwealth Games, the head of the Australian team, Arthur Tunstall, said, “She should have carried the Australian flag first up, and [we should have] not seen the Aboriginal flag at all.” Freeman wanted to shout: “Look at me. Look at my skin. I’m Black and I’m the best.”

Her loss to France’s Marie-José Pérec at the 1996 Olympic Games fuelled her desire to win.

The 400m final at the Sydney Olympics was expected to be a repeat showdown but Pérec pulled out of the race at the last minute due to the intensity of pressure over the home town favourite.

Freeman, too, felt intense pressure but it was pressure of a different kind. She carried with her the weight of expectation. It was a heavy load, but you wouldn’t know it looking at how elegantly Freeman glided on the track. “To me, running’s like breathing,” she’s said. “It’s something that comes really naturally and I’m good at it.”

Good is an understatement. In 2003, The Age declared Freeman “Australia’s greatest athlete in recent history and arguably its greatest ever.”

To be the greatest takes enormous dedication, a meticulous training schedule and plenty of natural talent. Freeman had all three, as well as something that set her apart: the spirit of her ancestors. “My ancestors were the first people to walk on this land,” Freeman explained in her self-titled documentary, released in 2020 on the 20th anniversary of her historic Olympic win. “Those other girls were always going to come up against my ancestors. Who’s going to stop me?”

That pivotal moment in 2000 was not Freeman’s only glory.

Ten days before the win, she carried the Olympic torch and lit the cauldron at the Opening Ceremony. In 1998 she had been named Australian of the Year, and in 2001 she was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM).

In 2005 she was inducted into the Sport Australia Hall of Fame, which then elevated her to Legend status in 2011. “I had a deadly sense of self-belief,” she has said. “I’d go to another level and say I had a deadly sense of self-conviction where you can say whatever you want, you can do whatever you want but you’re not going to touch me.”

For 22 years, since her first gold medal at her school athletics carnival, Freeman channelled her sense of self-belief into her running. She left it all on the track until she had nothing left to give.

In July 2003, aged 30, Freeman announced her retirement from athletics. “I’ve lost that want, that desire, that passion, that drive,” she said. “I don’t have the same hunger. I know what it takes to be a champion, to be the best in the world, and I just don’t have that feeling right now. I’m tired all of a sudden.”

Despite her tiredness, Freeman didn’t exactly slow down in retirement. She founded the Cathy Freeman Foundation to address the education gap between Indigenous and non- Indigenous children through education programs in remote schools, having been an ambassador of the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation.

Off the track and away from her charitable work, Freeman’s personal life encountered a mix of highs and lows. She was in a romantic relationship with her manager Nick Bideau that ended badly with disputes over endorsement deals.

In 1999, she married Nike executive Sandy Bodecker, who she cared for during a battle with throat cancer before they divorced in 2003, just months before she retired from running.

At the time, she released a statement saying, “It was always going to be difficult with one of us living in the United States and the other in Melbourne, and our respective careers have put extreme pressure on the relationship.

This has led to my decision to separate. I am looking forward to getting on with the rest of my life and I’m optimistically looking forward to the future.”

Her future included a two-year relationship with actor Joel Edgerton, who she was with until 2005.

The following year, Freeman announced her engagement to Melbourne stockbroker James Murch. The couple married in 2009 and welcomed their first child – a baby girl – in July 2011. Freeman’s daughter is following in her footsteps, winning races at school athletics carnivals.

As well as passing on her champion genes to her daughter, Freeman has paved the way for the next generation of First Nations athletes, as noted by former world No. 1 tennis player Ash Barty, who recently wrote, “We all remember with goosebumps when Cathy Freeman won gold at the Sydney Olympics in 2000 … Now I see it as my responsibility to guide First Nations youth and help create opportunity for them to go after their dreams.”

Freeman has always lived by mantras, from the motto she wrote on a poster as a child (“I am the world’s greatest athlete”) to the words she repeated to herself at the starting line of the 400m final in Sydney (“Do what I know”). She has long sported a very apt tattoo on her right upper arm.

It reads, “Cos I’m free.”

This story originally appeared in the March issue of marie claire Australia.