She was suffering severe burns across her back and arm, multiple shrapnel wounds and a deep gash in her wrist, but Megan Basioli knew she had to keep moving. Only she couldn’t. The searing pain was so intense for the 14-year-old from Perth that as she tried to stumble with her stepmother and stepsister down the dark, chaotic street in Bali’s Kuta district where devastating explosions had ripped through two nightspots, she kept falling to the ground. Then she felt herself being lifted from behind, as a stranger carried her to a nearby hotel, where other victims were being cared for by hotel staff, locals and tourists.

As she lay near the hotel pool, a teenager from Sydney named Craig, who was holidaying with his family, came and sat beside her.

“He just asked if I was OK,” Megan recalls. “He was staying at a hotel nearby and ran down with his family to help when they heard the explosions. I said, ‘Can you please stay next to me?’ And he did. He stayed with me the whole time. And when they took me to the hospital he stayed next to me there, too, just holding my hand.”

It is 20 years since the Bali bombings, a religiously motivated attack that killed 202 people from 23 countries, including 88 from Australia – the single largest loss of Australian lives due to a terror attack. Carried out by Islamist group Jemaah Islamiyah, the atrocity began at 11.05pm inside the packed Paddy’s Pub in Kuta, when a suicide bomber detonated explosives

in a backpack; 20 seconds later, a more powerful car bomb was detonated outside the Sari Club, opposite Paddy’s.

Megan lost her father that night of October 12, 2002, and underwent years of agonising rehabilitation for the burns that covered 36 per cent of her body. But it was what she witnessed in the aftermath of the terror that became the founding of her future.

“Everyone rallied to help,” says the now 34-year-old, who remains friends with Craig, now 36. “One of the main things I took away is how amazing humans can be in times of tragedy.”

Here, three women share their memories of one of Australia’s darkest nights, and how it changed their lives.

MEGAN BASIOLI, 34: THE SURVIVOR

Megan was 14 when she went on a family getaway to Bali with her dad, Peter Basioli, 44, brother Shane, 8, stepmum Lee-Anne, and stepsister Nadine, 15. After a Saturday night dinner, Peter and Lee-Anne took the girls to the Sari Club. The explosion killed Peter, a bottle shop owner and publican, and left Megan with horrific burns. At Royal Perth Hospital, she was treated by Dr Fiona Wood, who was named the 2005 Australian of the Year for her pioneering “spray-on skin” invention that helped many of the Bali survivors. Megan now works part-time as an emergency department nurse and a cosmetic nurse at a skin clinic.

I was 14 and in year 9 at Perth’s LaSalle Catholic College. Mum and Dad were divorced and my brother, Shane, and I lived with Mum. We would go to Dad’s every weekend. He lived with his partner, Lee-Anne, and her daughter, Nadine. Dad was a gentle giant – he was six foot five [1.95m] but very quiet. A very kind person.

I was close with Nadine and we were very excited to go to Bali. We did lots of hanging out by the pool and shopping. We knew they didn’t check IDs at bars and we pestered Dad and Lee-Anne to take us. We went out to dinner on the Saturday night and they finally caved in, saying, “OK, we’ll just go for a bit.”

It was really busy in the Sari Club. Nadine and I were just dancing and being silly. Then I remember being, like, frozen, and a bright light. I must have been knocked unconscious because the next thing I remember is waking up and being covered in rubble, with Lee-Anne laying across me. It was absolute carnage. There was a lot of screaming.

We made our way out of the wreckage onto a side street. Lee-Anne said, “I’m going to look for Nadine and your dad.” She came back with Nadine. She never mentioned anything about Dad at that point. And then we all kind of sat down together, to collect ourselves.

I remember lots of people running around, screaming. One guy came up, his arm was gone, and he was yelling at us to help him. He sat down and leant against me, but I was in so much pain I had to push him off. I didn’t know why I was in pain; I didn’t know I had burns.

Nadine had a lot of shrapnel wounds on her legs, and on her face. And one of her fingers was pretty much severed off. She ended up losing it. Lee-Anne had some burns.

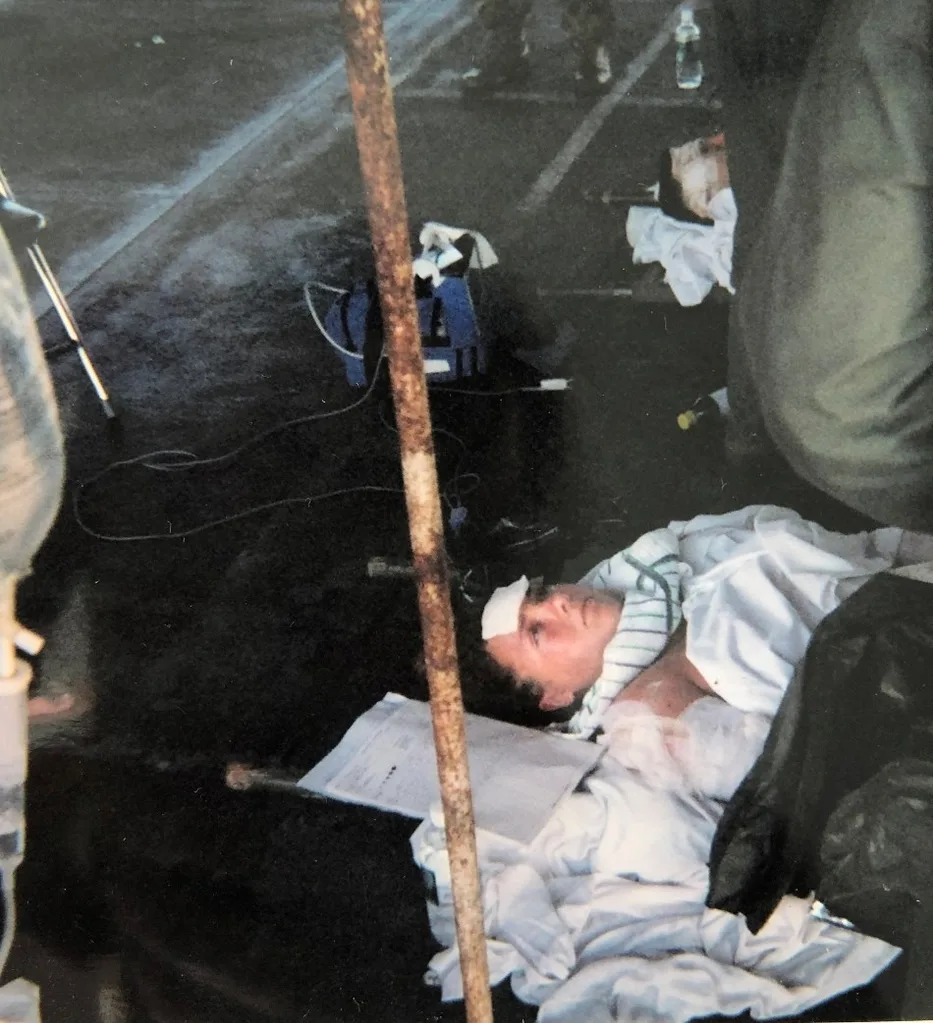

After a stranger carried Megan to a nearby hotel, she was taken to a local hospital. She was then medevaced to Darwin by the Australian Defence Force, before being flown to the Royal Perth Hospital.

I spent about 10 days in the intensive care unit. I had burns to 36 per cent of my body. Dr Fiona Wood treated me. She was just so kind. There was also a deep gash in my wrist, and they had to repair the tendons.

I remember being told Dad had passed away, but I was so overwhelmed with pain and fear I couldn’t really grieve. My uncle had the awful job of going to the morgues in Bali to find him. I saw his body arriving at Perth Airport. That was tough, just as hard as the funeral.

In hospital, it’s the nurses who are there 24/7. They would go above and beyond for you. It’s what inspired me to become a registered nurse. I work in the emergency department. I think a lot of people worried about me, including Fiona. One day we had a bad burn case come in and Fiona said, “Are you sure you’re OK to do this?” But I find it therapeutic to be able to give back.

I’ve definitely had moments of anger that this happened to me, and that my father was taken from me, but I’ve never really felt anger towards the people who did it. I just never grasped how someone could do that.

I look back now and feel that what happened to me made me a stronger person. I value the level of resilience it’s given me. One of my biggest challenges is strangers asking about my scars because each time I relive that trauma. But the scars are just a part of me. I’m kind of proud of them in a way.

BLAIR CEARNS, 50: THE SISTER

Gold Coast personal trainer Blair Cearns had just finished feeding her six-week-old baby, Mackenzie, on the morning of October 13, 2002, when she learnt of the explosions in Bali. Her older sister, Jodie, 35, a hairdresser turned hair-product sales rep, had been holidaying on the Indonesian island with five friends. Jodie survived the explosion at the Sari Club but succumbed to her injuries 10 days later.

Jodie was a seventh-generation hairdresser. Our mum was a hairdresser, and Jodie did her apprenticeship under her.

She was always the life of the party. When she was younger, Jodie was the wild one. She always had the brightly coloured hair and the different clothes. She was just so vibrant. And people loved her.

She used to go to Bali every year with her friends. Before she left in 2002, she met my first-born, Mackenzie, just a couple of days after he was born. That was the last time I saw her. She then flew down to Melbourne to watch the Brisbane Lions in the AFL grand final, and then she flew to Bali.

On the Sunday morning of October 13, I found out there had been a bombing in Bali. We couldn’t get hold of Jodie. We learnt that she had been at the Sari Club with her friends, but they had all been accounted for. They were searching the hospitals.

In the end, we found out she had been medevaced to Darwin. My mum and dad and older sister flew there. Jodie was in intensive care at the Royal Darwin Hospital. My family rang me and said, “You need to get here. She’s not going to make it.”

I flew to Darwin with my baby. When I saw Jodie, I didn’t recognise her. She had burns to 40 per cent of her body and there was a lot of swelling. She’d lost a leg and an eye. She was identified by her headband and her painted toenails, which she had done in Bali. Mum washed her hair because it was so bad with all the ash and dirt. I think that helped Mum, to be able to do that.

From Darwin she was flown to Melbourne, to the burns unit at The Alfred Hospital. So we flew there. Things improved for a while, and I actually flew home. That’s when Dad rang me to say she had passed away, on October 22.

Every year on her birthday in December we meet her friends at the Story Bridge Hotel in Brisbane and have a drink. She loved it there and the owners loved her. There’s a plaque there for her that reads, “In memory of the beautiful girl whose love of life touched us all.”

It’s still raw that she’s not here. It was terrorism but I call it murder. I’m missing out on her; my kids are missing out on her. It doesn’t get any easier, you just learn to deal with it a bit better. I just wish she was here.

YVONNE SINGER, 53: THE NURSE

In 2002, registered nurse Yvonne Singer was the care coordinator for burns and plastic surgery at Melbourne’s The Alfred Hospital burns clinic, where she still works today as the Victorian Burns Program coordinator. After the Australian Defence Force evacuated the casualties from Bali, at least 66 patients were triaged at the Royal Darwin Hospital. Most were then flown to burns units throughout Australia, including to The Alfred.

It only takes five patients to overwhelm a burns service. On Monday, October 14, we had nine patients come in. I worked with the doctors, planning the patients’ care when they arrived at the emergency department. Some of them needed to go to surgery quickly. We didn’t know who they were; many had stickers on them with their names, that was it.

They all suffered burns but some also had traumatic injuries. Some patients had lost legs and arms. We needed skin to cover their wounds. We can take skin grafts from one part of the patient to repair the wounds, but if a patient has 60 per cent burns to their body it doesn’t leave a lot of skin left. In surgery, we removed all the dead tissue and covered them with new bioengineered skin substitutes. Some patients had unsurvivable injuries [and] there was an urgency of finding their families, because you want them to have some time together.

It’s horrible to lose a patient. When I came home at night, I never read the newspaper or watched the news because knowing more about the patients was too much at the time. Many of the patients suffered psychologically due to flashbacks, especially at night. For example, barricading the door of their hospital room with furniture, making it hard for staff to enter the room.

One of our patients was the AFL footballer Jason McCartney. [In one of the sport’s most memorable moments, McCartney, who was burnt to more than 50 per cent of his body, returned to play for North Melbourne on June 6, 2003, before announcing his retire- ment at age 29.] He invited us all to the match. It was a public show of personal strength. And it was great to see.

I’m proud of my involvement and what we achieved as a team. I feel like all Australians wanted to help and we were in a privileged position where we could make a difference, to right this wrong.

This story originally appeared in the October issue of marie claire Australia.