“It’s pretty shocking,” Nicola tells me from her quarantined hotel room at Sydney’s Intercontinental. Arriving into Australia this week from London, Nicola was escorted by the Australian Defence Force straight to the state-funded room, where she will stay for a period of 14-days amid the COVID-19 pandemic. While Nicola was fully aware of the laws prior to boarding her flight and agreed to comply – what she and other passengers now face is an entirely different reality.

“A lot of people on the outside think that we’ve got it good,” says an audibly frustrated Nicola. “It very much feels like we are prisoners and the only thing getting me through is hoping that it will get better.”

After living in London for the past year and a half, Nicola decided to come home to Australia amid the COVID-19 pandemic to receive better support and security. Hopping on a British Airways flight, Nicola was told the long haul journey would have a “limited food service”, with passengers being fed three bread rolls and three chocolate bars throughout the 14-hour ordeal.

Arriving into Australia exhausted and hungry, she was quickly escorted onto a busload of passengers – where government officials and ADF did not follow state-mandated social distancing. In fact, people arriving from some of the most infectious cities in the world were seated next to one another in the confined space. “I put my bag next to me hoping no one would sit next to me, but there was someone behind me, in front of me, on the next seat across. Everyone was sort of packed onto these buses.”

While the reality of how bad the situation might get started to sink in, Nicola began to feel faint after not having eaten since departing London. “Breakfast never came. Lunch never came,” she recalls. “I was calling and calling, asking, is there something coming? I’d called them so many times.”

It was three hours later, when her food still had not arrived, that Nicola began to panic. Eventually, she decided to call the designated medical line to tell them she was feeling unwell not having eaten a proper meal. “Since then, I’ve had to call them every time to get my meal.”

On top of that, Nicola gave directives that she was vegetarian but so far has received only one meal that does not contain meat. “I would much prefer to pay for my own food,” she says, only to be told that delivery services will be unavailable for the quarantine period. Friends and family were also not allowed to leave food at the hotel.

The hotel also said it would replenish toiletries, but Nicola has been left without basics like toothpaste. Upon calling several times, she had still not received any, which led her to ask for tampons too.

They still never came.

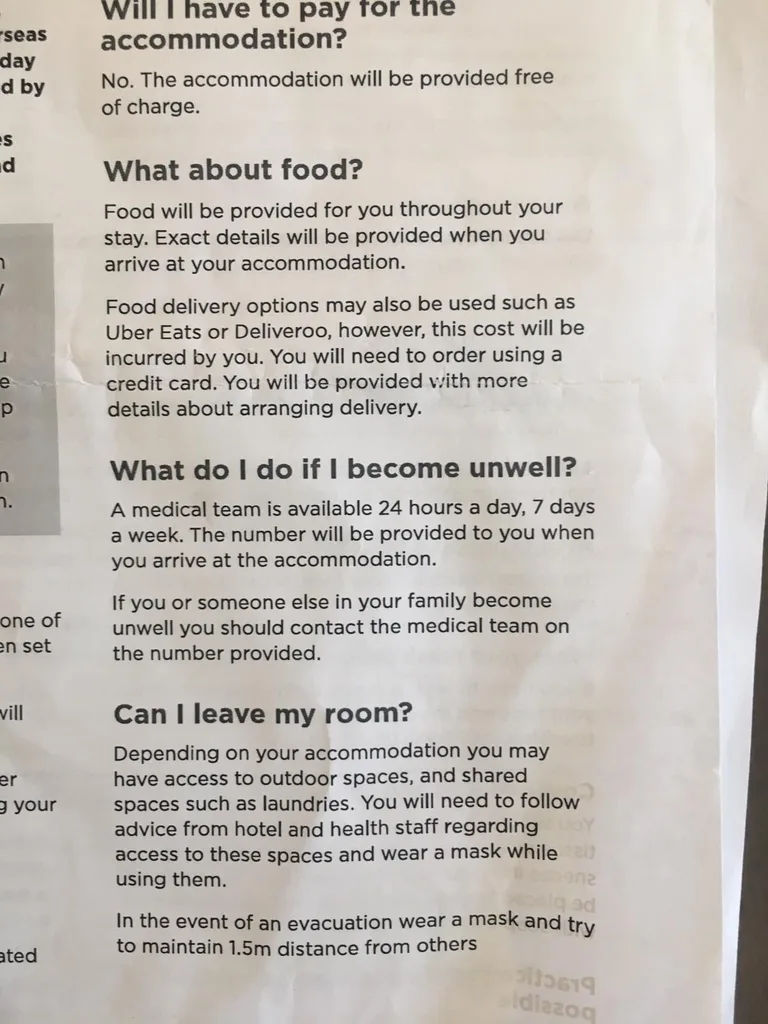

What is possibly most shocking to Nicola is the information provided prior to the quarantine varies so much from reality. Looking at a pamphlet in front of her she reads to me, bullet point after bullet point of misguided information.

It’s the reality that this experience may eventually take its toll on her mental health that Nicola admits is the most terrifying. Her room, which she admits is not terrible considering, does not have a window that opens or a balcony, meaning she’ll get no access to fresh air for 14 days.

“I don’t think that they’ve thought about adequate mental health support for people,” she says. “There is no psychologist on site. There’s no sort of team of people checking on people’s wellbeing. They gave us a number for Lifeline and that’s it.”

“I am genuinely really worried about how this will affect my mental health,” she adds.

On day three, a mental health service personnel was assigned who would call daily to check on her wellbeing. She is still awaiting the call.

“I just don’t know how this is allowed.”