Australia’s first dedicated egg-freezing clinic opened late last year, promoting the procedure as an insurance policy against infertility. But does it represent hope, hype or heartbreak?

On a crisp Thursday night in Sydney, women are arriving on the third floor of a slick city skyscraper. They’re greeted with sparkling wine and ushered into a bright white Hamptons- style kitchen, with pendant lights hanging overhead and a huge island bench topped with finger sandwiches and fruit skewers. But aside from the smattering of sharp suits and Louboutins, this is not your standard after-work mixer. Women stare steadfastly at their phones, deliberately avoiding each other’s gaze. The tension is thick, the silence loud. The clock on the wall ticks rhythmically in the background. Perhaps it’s a metaphor: for many of the women here, the beat of their biological clock has become an eerie internal soundtrack.

Tonight’s guests are at Genea Horizon, Australia’s first dedicated egg-freezing clinic, which opened in November last year. Ella*, nearly 33, is attending the information session because she’s always assumed she’ll have children one day but hasn’t found the right partner. Her dad has said he’ll pay for her to freeze her eggs, and her sister, who has three kids of her own, has encouraged her to consider the procedure. But Ella’s unsure about the side effects, and the whole thing stirs up an emotional cocktail of fear and failure.

She makes her way to the presentation area. People are clustered up the back like it’s a first- year university lecture, and everyone’s sitting one seat apart. As the lights dim, soothing harp music begins to play and a series of statements and questions ash across the white projector screen: “Do you want to have children?” “Live in the present, but don’t forget to plan for the future.” Some call the egg freezing drive a feminist game-changer: just like the pill liberated baby boomers, egg-freezing could emancipate millennials. But it’s ringing alarm bells for critics, who claim the medical procedure is being sold as a misguided lifestyle choice to young women, offering hope with no guarantees of success.

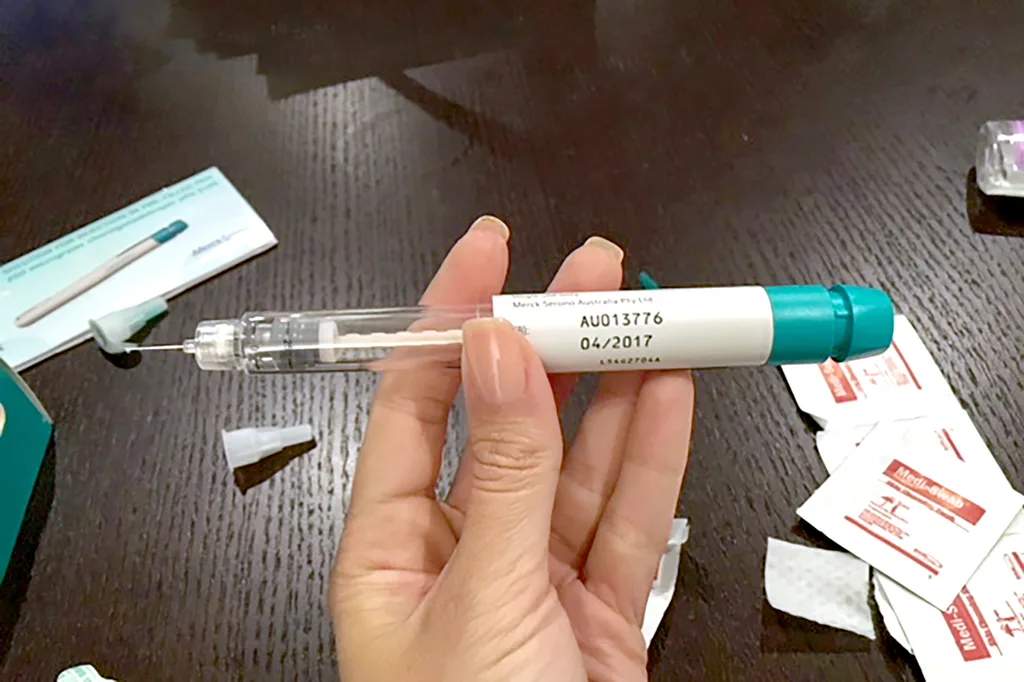

Egg-freezing, or oocyte cryopreservation, is the process of extracting, freezing and storing a woman’s eggs so she can – in theory – use them to have children in the future. It involves stimulating the ovaries with hormone injections to produce a surplus of eggs, which are then collected during surgery. When a woman wants to try for pregnancy, one of her eggs will be thawed, fertilised and – if it survives those procedures – implanted in the womb.

While embryos and sperm have been frozen for decades, egg cryopreservation is relatively new and has much lower success rates than the implantation of frozen embryos. Historically, few eggs survived the freezing process, but in 1999 an ash-freezing technology called vitrification was introduced that radically improved out- comes. Nine years later, Australia’s first “frozen egg” baby was born in Sydney. Since then, the procedure has shifted from purely medical (it was mostly used by cancer patients and endometriosis sufferers who might be at risk of later infertility), to an elective or “social” choice undertaken by healthy women – often single or simply not yet ready for motherhood – as a fertility “insurance policy”.

Now, social egg-freezing is heating up in Hollywood and hitting the headlines. A recent episode of Keeping Up with the Kardashians focused on 39-year-old mother-of-three Kourtney considering the treatment to keep her dreams of more babies alive. Rita Ora, Olivia Munn and a crop of former US Bachelor contestants have all frozen their eggs and preached the benefits, moving the matter squarely into the mainstream.

“We’ve seen a 50-to-100-per-cent rise in patients in the past year,” says Dr Devora Lieberman, a fertility specialist at Genea Horizon. “Originally, egg-freezing was directed at older women – 38- or 39-year-olds, even those in their early 40s – and unfortunately by that age we’re probably freezing a woman’s infertility as opposed to her fertility. Genea has tried to make egg-freezing as affordable as we can so that younger women can … access the treatment too.”

As we’re regularly reminded, a woman’s fertility starts to decline at the ripe old age of 22, dropping significantly at 35, 38 and 40. While we’re born with up to two million eggs, we lose 90 per cent of them by the time we’re 30. At 35, our chance of getting pregnant naturally in any given month sits at 15 to 20 per cent.

Here’s the conundrum: we’re working harder, travelling more and settling down later than ever before. Women’s lifestyles have changed dramatically, but our biology has not. Stowing away some eggs sounds like a reasonable solution, postponing procreation and future-proofing one’s fertility in one fell swoop. Yet statistics to date don’t match the hype. In the past 30 years, an estimated 2000 “ice babies” have been born around the world using frozen eggs (most to cancer patients). Lieberman explains,

“Whether we’re in Spain, Sydney, Melbourne or New York, fewer than 10 per cent of women who’ve frozen their eggs will ever come back and use them.” Which could beg the question: what’s the point?

Dr Nikki Goldstein, a sexologist and author, first learnt about egg-freezing from an American dating coach who advised her to look into the procedure. “I’m very free-spirited and like to travel. I never thought I had to rush out and get married, but I always knew I wanted to be a mum,” says the bubbly blonde. “I froze my eggs just before my 30th birthday. The hardest part was having people look at me like I’m crazy and say, ‘But you’re so young!’ Well, yes, I am young, but have a look at 30 biological years in terms of where your reproductive health is … I did it for my future self as a partial back-up plan.”

For two weeks, Dr Goldstein injected her belly with follicle-stimulating hormones. “You kind of feel like an egg farm,” she says. “I was crampy and got really bloated at night. I went in with a positive mindset – I knew this wasn’t my last chance at motherhood – but it was still a head spin. At times I was an emotional wreck.”

The procedure, says Dr Goldstein, didn’t silence her biological clock, but it did take some of the pressure of dating. “When I met my current partner, he wasn’t right on paper, but there was a strong connection and intimacy there,” she remembers. “Instead of freaking out that we weren’t compatible I was able to be in the moment with him. I thought, ‘I’ve got the eggs in the freezer; if this doesn’t work out I’m still OK.’ I’m so thankful I got that headspace.”

Most fertility specialists recommend undergoing the treatment before turning 35, although women in their late 30s and early 40s have been, until now, the primary market. “I see women in their 40s who are well aware their frozen eggs are highly unlikely to become babies in the future, but they are needing to resolve their issues around their childlessness,” says Dr Lieberman.

Paradoxically, women in their 20s generally don’t have the desire, sense of desperation, or dollars to put their eggs on ice. Costs for the treatment vary, but one cycle – including medication and egg storage – will set you back close to $10,000 (more cycles may be required to retrieve more eggs) Medicare rebates are only available for women using the service for Medicare reasons.

Across the Pacific Ocean, the business of egg-freezing is booming. From Silicon Valley to Seattle, women are heading to “egg socials” – next-generation Tupperware parties that promote cryo over cocktails. Many come with loaded slogans: “Lean in, but freeze first”; “Freeze, retrieve, relax”; and “Eggs do go bad. Have yours?” Meanwhile, online forums discuss egg- freezing retreats, such as an upcoming getaway in California’s Monterey (Big Little Lies territory), where hormone-pumping will be sandwiched between spa treatments and yoga.

The glamour of it all has raised some ethical concerns. “Are we dealing with a commercial product where the general rules of marketing apply, or are we dealing with a medical procedure where there needs to be some professional oversight from medical bodies?” asks Dr Christopher Mayes, researcher at Deakin University’s Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation. “Are we talking about patients or are we talking about customers?” Bioethicist and lawyer Dr Josephine Johnston, a New Zealander based at The Hastings Center in New York, says, “It’s worrying that egg-freezing is being promoted at parties where alcohol is served. It’s so incredibly different from how you would usually counsel a patient about a medical procedure. It supports the claim that the procedure is being sold as a lifestyle choice.”

Cavalier marketing, she continues, is likely to gloss over the often-harrowing and heartbreaking realities of egg-freezing. “You have to wonder, are the women at these parties aware that the procedure is a real medical experience with medical risks [such as infected or hyper-stimulated ovaries], and that it will lead to more medical experiences, such as IVF?” The lack of statistics on success rates only adds to the murkiness. Brigitte Adams was 39 when she decided to freeze her eggs in 2011. She was a single woman making her mark on California’s tech-marketing scene and found the idea of putting her eggs on ice liberating and exciting. Adams started a blog, eggsurance.com, which grew into a thriving online community for the egg-freezing sisterhood. Her image was splashed on the cover of Bloomberg Businessweek under the headline, “Freeze your eggs, free your career”.

By early 2017, Mr Right still hadn’t materialised, so Adams, then 44, selected a sperm donor and eagerly prepared for single motherhood. She thawed her 11 stored eggs, but only one developed into a healthy embryo. Adams miscarried within a few days. Just like that, her long-held hopes – which had gradually morphed into staunch assumptions – were crushed. Adams would never hold her own genetic child.

After crying “like a wild animal” and scratching her face “so hard it bled”, she took to her blog to reflect. “Freezing your eggs is easy,” she wrote. “You’re in this sort of Disneyland world of fertility where everything’s possible. There’s no next step to it. You’re done, you compartmentalise it, you move on with your life. Things get hard when you’re actually moving on to step two and completing the process. I am by no means anti egg-freezing, but today’s [commodification of the process] concerns me deeply, as clinics are failing to transparently present egg-freezing risks, data and the success rates (or lack thereof).”

In fact, the main data many of these clinics seem to be preoccupied with is profit. In the past five years a number of fertility clinics have been publicly listed (including Monash IVF and Virtus Health in Australia), bringing shareholder considerations into play. As such, “these clinics are always looking for new markets”, says Dr Mayes, citing younger working women as the next target.

And other corporations are only too happy to help. In 2014, the US arms of Facebook and Apple announced they were offering to pay for female employees to freeze their eggs. Call it a company perk, along with a gym membership. Both companies declined to speak to marie claire, but according to Reuters, Apple subsidises the procedure up to $20,000 USD per individual. Last November it was reported that a number of major Australian companies are planning to follow suit.

Corporate egg-freezing is a contentious issue. On the one hand, it’s a generous benefit for an individual, especially one faced with the possibility of a childless future – however critics warn it could encourage employees to work through their prime child-bearing years with no guarantee of later success. “Given our workplace structures, I can absolutely see why an individual would take it up,” says Dr Johnston. “What makes me sad is that it’s a way of coping with a broken system, like a Band-Aid solution.”

Perhaps it is time to redesign workplace structures – not the women in them. More paid maternity and paternity leave, on-site childcare, flexible hours and equal pay could all create a climate where women don’t need to choose between having a family and a high- flying career.

Dr Johnston also believes we need to look at the role men play in the fertility (or infertility) conversation. “Why is it that women might find themselves in their 30s without partners? What are the male/female dynamics contributing to [this]? We’re just ignoring the underlying pressures that lead to this situation, and reframing it like it’s an empowering choice,” she says. “I have an eight-year-old daughter and if she says to me in 20 years’ time that she thinks she needs to freeze her eggs, a part of me will feel like we failed, that we didn’t fix the issue that makes a woman feel she needs to do that – that it’s all on her”

On February 6 this year, Kylie Jenner’s baby-name announcement became Instagram’s most-liked-ever post with a cool 17.8 million thumbs-ups. Seven out of the app’s 10 most popular images depict pregnancy and birth. Meanwhile, the media is rife with stories about “poor Jen [Aniston]” and “childless Kylie [Minogue]”, reinforcing every last trope about the desperate, barren woman. It’s no surprise then that women often feel a deep angst to reproduce, or that beneath the shiny packaging and promise of hope, egg-freezing sessions are sombre affairs. For some individuals, reproductive technology will afford a sense of control; for others the choice will become a source of anxiety, fraught with future disappointment.

“It’s never up to me to say whether a woman should [freeze her eggs]; she has to be comfortable in her decision,” says Dr Lieberman. “The last thing I want is to create a whole new generation of women who are disappointed if technology fails them. I describe egg-freezing as an insurance policy against regret. But there’s no right answer.”

Ella ultimately decided not to freeze her eggs – for now, at least. This month she’ll renew her health and car insurance policies, but she’ll leave her fertility up to fate. Maybe she’ll meet someone and have a baby like she always hoped, but if she doesn’t, perhaps that life could be OK too. No insurance policy, no regrets.