2020 has forever changed the way we live and think, bringing opportunity for growth and positive change. Ten high-profile Australians reveal their hopes for the future.

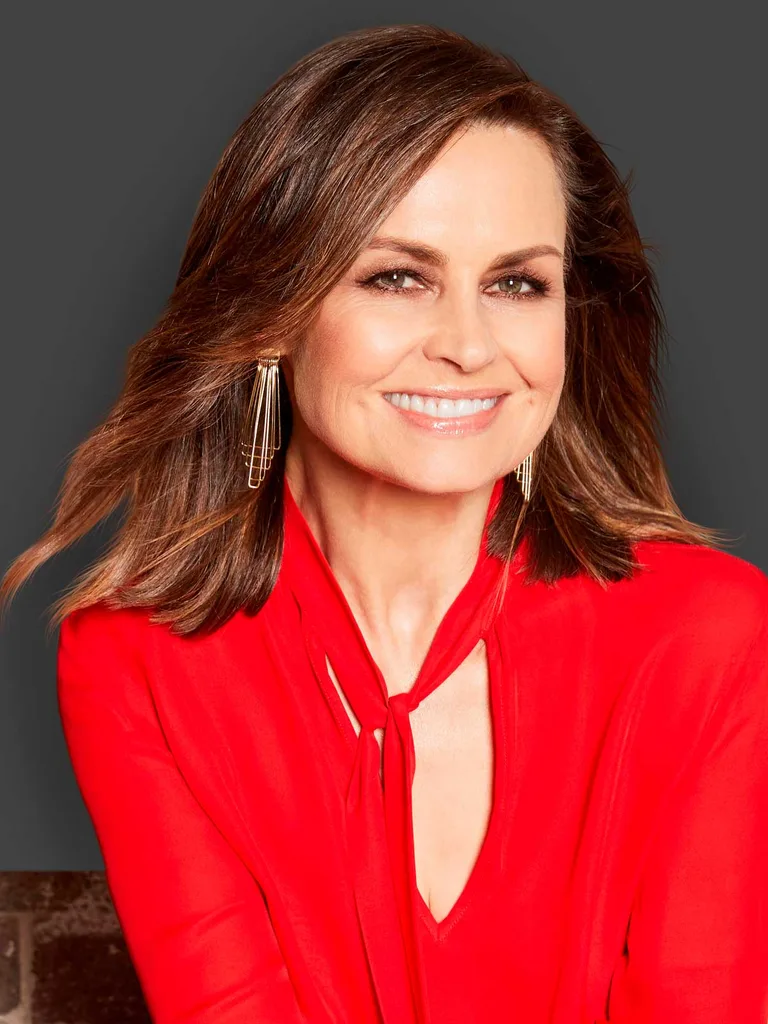

Lisa Wilkinson

Co-Host of the Project

This is a year none of us saw coming. Or maybe we did and chose not to look. But what if 2020 was the year the universe decided we had to have? What if this was the year the universe chose to say “enough”? The year Mother Nature sent us to our rooms to take a long, hard look at ourselves?

It’s a time to be uncomfortable with where we are and what we may have become. A time to pause, to pivot and to plan. A time to realign our values. A time to breathe real, clean air and to think, mindfully. A time to treasure our health. A time to support local business and embrace our community, our neighbours. It’s about time with family, untrammelled by the distractions of a world moving way too fast. And time with ourselves, our thoughts and the dreams we somehow abandoned because… life. A time to move forward with more compassion, less judgement and more gratitude. A time to make change and be the change.

I pray that what has not broken us in 2020 has woken us. I dream that we will all now breathe a little deeper and pause a moment longer, having discovered a better soul, a stronger spirit, a more mindful, conscious self. Living with the knowledge that we all need to fit more gently into the universe.

Benjamin Law

Writer and Broadcaster

George Floyd’s brutal killing at the hands of police – and the wave of Black Lives Matter protests in its wake – have made us all re-examine police brutality against black people in the US and Australia. Here, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people represent roughly three per cent of the population, yet almost 30 per cent of the prison population. Since the 1990s, hundreds of black people have been killed – and continue to be killed – in police custody in similar ways to Floyd. In 2015, David Dungay even said the same words as Floyd – “I can’t breathe” – as he was held face-down by police officers before he died. What happens to black kids and adults in Australian detention is a national stain.

It also forces us to look at all our institutions with critical eyes. The arts and media govern whose stories are told, and who gets to tell them. And although we live in a country with the oldest continuing human civilisation on Earth, where half of us are first- or second-generation migrants … where are non-white people in the national conversation? Off the top of your head, can you name 10 Australian TV shows starring or hosted by a non-white person? Or even five?

Conversations about “diversity” in 2020 shouldn’t make us feel good. They should make us look at our leaders and propel us into action. May 2020 be the year we get comfortable discussing “whiteness” the same way we do “patriarchy” – recognising that the issue is how to address disproportionate imbalances of power that erase other people.

Tayla Harris

AFLW Player and Professional Boxer

Eternally optimistic, I see a future Australia that generates equal opportunities for men and women and is a country proud to boast the highest standards of acceptance.

I hope it is a place where aspiring female athletes are not challenged by multiple barriers that prevent them from achieving their dreams, while their

male counterparts follow the yellow brick road to becoming professional sports stars. We don’t mind if our brick road isn’t yellow, hell, paint it rainbow and give a voice to the LGBTIQ+ community too – women are multitaskers after all, aren’t we?

I am ambitious by nature, so I refuse to tone down my optimism. I believe many Australians’ attitudes need to change, but I do believe gender equality in sport is possible. I would also love to see the end of the tall poppy syndrome in Australia, replaced by a culture where we support each other and celebrate our achievements.

Lastly, I see an Australia that is devoid of bullying. I am often in disbelief at the public display of bullying by our politicians. It is clear that it is a ‘top down’ issue – young people see our leaders disrespecting each other, raising their voices, shaming each other’s work and they think this is OK. It then bleeds into the school rooms, social gatherings, online – a vicious cycle.

Meanwhile, I will continue to live my life with my values in check – kindness, bravery, empathy (among others). I hope to inspire, I hope to make change and I hope we stop hoping and start doing. Dare to dream, right?

Kylie Kwong

Chef and Resturantuer

Soon after lockdown, like so many, I was at home, trying to think of ways I could support. After speaking with several individuals in leadership roles of essential community and health organisations, I felt both humbled and motivated.

After 20 years of running my own business, I have an understanding of what it’s like to be “leading” all the time, being the “boss”. Even when you work in a collaborative way, as all of the above do, the buck still stops with you. I had 40 staff at Billy Kwong – so many livelihoods to be responsible for. That said, I could not even begin to imagine what these leaders have to manage and carry as they deal daily with intense, volatile situations with the most vulnerable in our society.

So, every Saturday, I delighted in cooking fresh food for these leaders: Siobhan Bryson and Mardi Diles of Weave Youth & Community Services, Helen Silvia of Women’s and Girls’ Emergency Centre, Ronni Kahn of OzHarvest, Rob Caslick of Two Good Co, local elder Aunty Ali Golding and Jon Owen of Wayside Chapel.

After listening to what they have been dealing with, as they and their extraordinary organisations stood at the coal face of such adversity, it suddenly struck me: who was looking after them? How did they maintain their own mental, emotional, physical and spiritual health while dealing with everyone else’s anxieties? We must not forget that leaders and bosses – like all of us – need time and space to let their guard down, to be vulnerable. They also need comfort, nurturing and care. Giving energy to these leaders in the best way I know – through cooking and offering food – was a small yet hopefully meaningful way that indirectly supported the thousands they help, each and every week.

As we gradually make it to the other side, we must not look at bouncing back but, rather, bouncing forward. Collectively, we must make care our central mission.

Lidia Thorpe

Greens MP

As a Gunnai and Gunditjmara mother and grandmother, I believe that all of our children deserve to be safe. I am committed to raising the age of criminal liability. This is the age at which a person can be arrested, charged and found guilty of a crime. That age is currently 10 years old in this country. This has meant that,in 2009, a 12-year-old boy was taken out of school, arrested and charged with receiving stolen goods because he accepted a stolen Freddo frog from a friend. In 2000, Johnny Warramarrba committed suicide in Northern Territory’s Don Dale prison after being locked up for stealing stationery. These are our babies. Our babies belong with their families. These children need to be connected to communities and country. An identity is what creates a strong person and our identity is with the land. Prison is no place for a child to develop. Our children should be loved and nurtured and be a part of the community.

The international average age of criminal liability is 14 years old. I think it’s about time our nation catches up with global human- rights standards. As the Greens Senator for Victoria, I’m passionate about taking this struggle to parliament, as I believe all our kids should feel safe around police and know they can go to them for help – [rather than] recoil in fear. I always get asked by non-Indigenous people how they can be better allies to Aboriginal people. Listening to truth- telling about our fight for justice is a good start. Maya Newell’s 2019 film In My Blood It Runs does this elegantly and effectively.

Mariam Saab

Journalist and ABC News Presenter

“She’ll be right, mate” is as Australian as Vegemite, but like our beloved spread, it doesn’t work with everything. If the hard knocks of a merciless bushfire season, global pandemic, systemic racism and inequality, press freedom wars, toilet-paper brawls and so on have you sagging on the ropes, you’re human. This is not a bad roll of the Jumanji dice – however unreal it feels. This is our “forged from the fire” moment and far from the first. Growing up an Australian-Lebanese Muslim in the Sutherland Shire during the Cronulla race riots taught me this: multiculturalism is the great strength of our country. “Going back to where you came from” doesn’t mean you belong there. In the Middle East, I was the Aussie journo, while in Europe, the Anglo. My kids are tri-lingual, tri-national Peppa Pig worshippers of both Christian and Muslim ancestry. My son’s greatest passion is surfing. Legit shredding.

If multiculturalism is our bread, then mateship is our butter. We’re all farmers in drought, communities devastated by fires and floods, victims of family violence, LGBTQ and proud, health and emergency workers, asylum seekers in detention and, just as my husband fled Lebanon to France as a child refugee, we are all in exile. I still feel like the odd dark girl with the smelly lunch box in a playground full of beautiful blondes. But now the playground is Australian TV. It’s time for change. Time to shout Black Lives Matter. Our First People matter. It’s time to take action on climate change, to defend a free press and demand that it asks itself as many questions as it asks of others. And, once in a while, we’ll turn down the news and politics and turn up Slim Dusty, and in that great Aussie drawl we’ll sing, “She’ll be right, mate.”

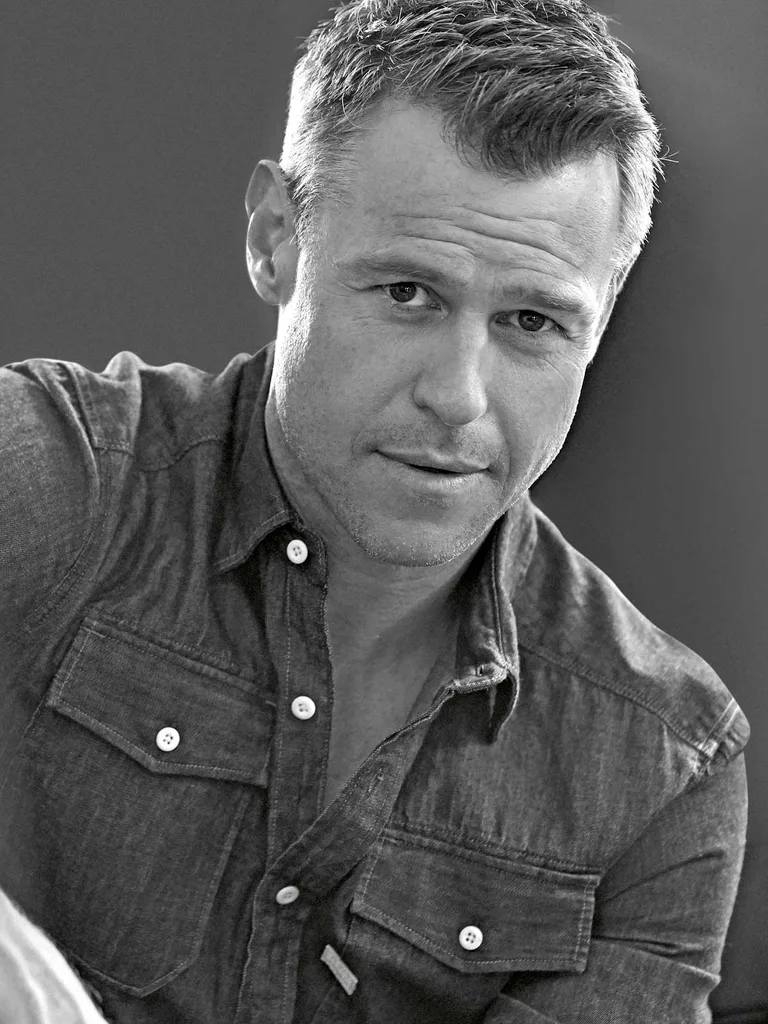

Rodger Corser

Actor and Producer

Shareena Clanton

Actor and Rights Activist

Historical self-identity, colonial propaganda and the status quo become the path of least resistance for many Australians. The truth is, on a national average, Indigenous youths are at least 23 times more likely to be incarcerated from the ages of 10–17 than non-Indigenous kids.

Such punitive social policy feeds into privatised prison systems and the flourishing of a multi-billion-dollar industry of Indigenous oppression and incarceration. It is a business of power and colonial rule built fundamentally on criminalisation, dehumanisation and enshrining of us as the “other”, less than, a subhuman minority.

Representing less than 3.3 per cent of the population, we cannot fight this war on our own. The language of revolution is not in those who buy their way into boardrooms or influence policy by political affiliation.

Political and corporate erasure of Indigenous post-colonial history laid a foundation on which genocide was built. Indigenous suffering need not exist as an underpinning virtue of nationhood. The vocabulary of oppression is not the language I frame my people’s resistance in.

With a crystallised understanding of Indigenous truth among the broader population, change is possible. Work with me in disseminating that truth. Truth is magical.

Clementine Ford

Author and Activist

It’s tempting to look at the events of this year and think of them in negative terms. But there is opportunity in this pandemic: we are being shown alternative endings that will take us to new and better places.

For one, a new understanding about the impact of gender inequality is being felt in homes all over the country. As COVID-19 demands that people stay home and work, we can craft a new way of living that enables parents – and let’s face it, mothers especially – to be creators and contributors equally, rather than being sidelined for convenience.

But beyond this, there is a softer, gentler way of being, too. A return to the roots of connection, even as we are prevented from connecting. Neighbourhood walks with tumblers of wine or hot toddies. Patronising the small businesses in our suburbs. Saying “hello” to people as we pass them on the street. I want to believe in the inherent capacity people have for kindness.

My Australian dream is that we don’t rush back to reestablish the old world order, because frankly it sucked for a lot of people. Let’s come up with a better vision, one that is validating for all people and recognises the community we are a part of. Oh, also more wine sold in cans, please.

Natasha Stott Despoja

Chair of Our Watch

My hope for the future is for a violence-free Australia. Every week in Australia, on average, a woman dies violently, usually at the hands of someone she knows. Police get called to a domestic violence incident roughly every two minutes – that’s 657 times a day. Violence is perpetrated against women of all backgrounds, young and old, women of colour, lesbian, bisexual and transgender and women with a disability. The rates of violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are Australia’s particular shame.

The good news is: violence is preventable. We need to embed gender equality in all the places we live, learn, work and play – from schoolyards to decision-making institutions.

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of marie claire.